Erik Satie: Sports et Divertissements

Erik Satie

Erik Satie‘s piano cycle Sports et divertissements was inspired by twenty drawings by the caricaturist Charles Martin, or perhaps it was the other way around: it was Satie’s ideas for the music that inspired the artist. However, neither of these statements is true. Martin was commissioned and delivered his artwork and then Satie was commissioned to write the music, but without having seen what Martin produced. And, to compound the influence question, the pictures that Martin created when Satie was composing were not used for the final production.

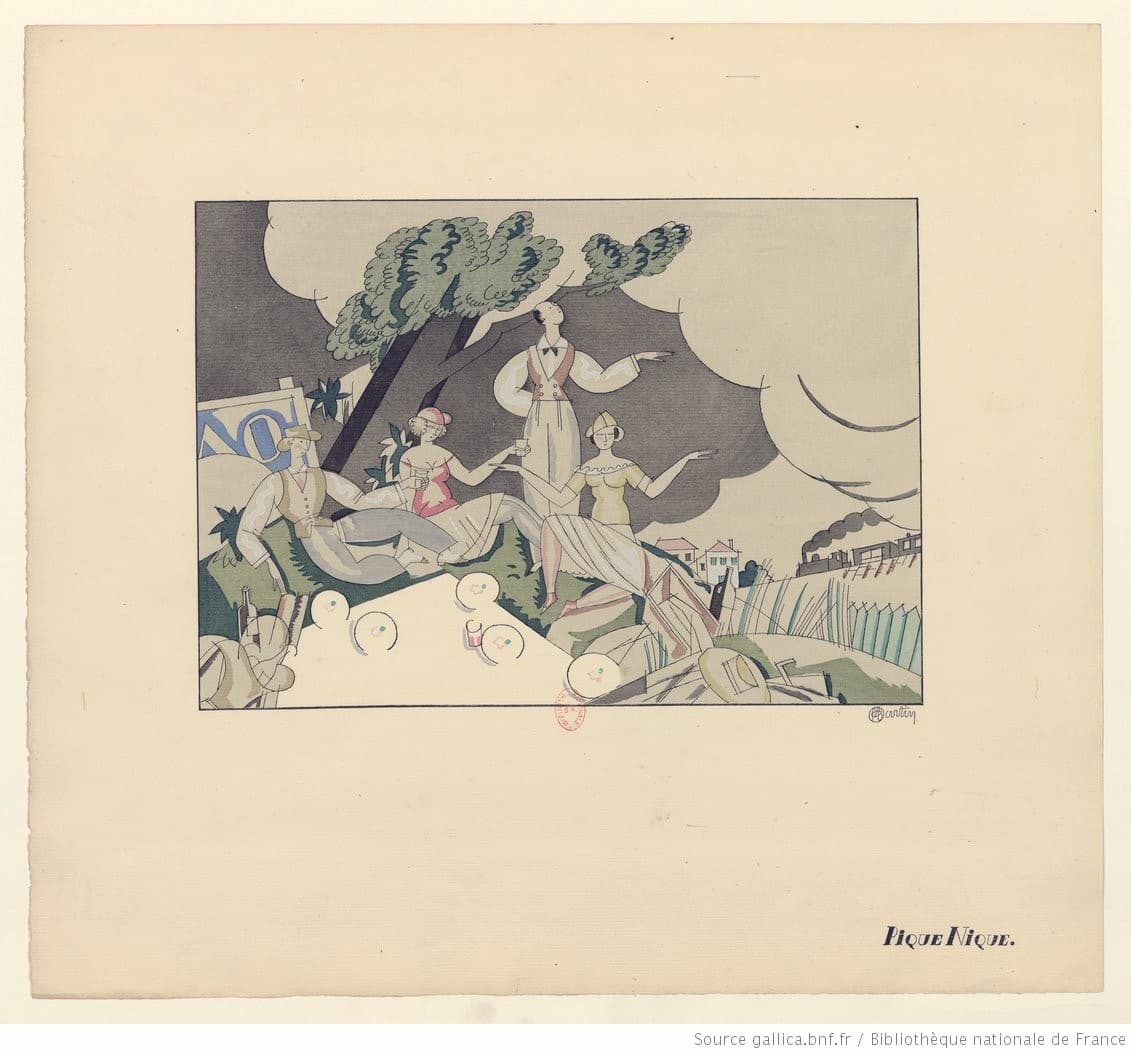

Charles Martin: Le Pique Nique, 1914

Let’s go back to the creation of this work. It all started when the publisher Lucien Vogel had an idea for an artist’s book. Vogel was the publisher of La Gazette du Bon Ton, the influential Paris fashion magazine, and the intention was to show the latest fashions of the affluent while at play. An artist’s book was an extravagant limited-edition book that usually centered on an artist but that might have associated prose or poetry, or even music with the illustrations. Bon Ton illustrator Charles Martin created 20 copper engravings based on subjects that Vogel devised, Stravinsky was approached to write the music (but declined because the fee was too small) and then Satie was approached (he nearly declined because the fee was too large!), and in 1914, the work was complete.

Charles Martin: Le Pique Nique, 1922

Then came the war. All art book production ceased and Vogel closed his company in 1916 with the death of his partner. The project languished. The music plates (in 2 colours) and the copper-plate engravings were sold to ‘Mr. Maynial.’ After the war, Vogel set up a new company ‘Les Editions Lucien Vogel et du Bon Ton’, purchased back the rights from Maynial, and then commissioned new drawings from Martin because the 1914 designs were too old-fashioned looking for anything associated with Bon Ton to be publishing.

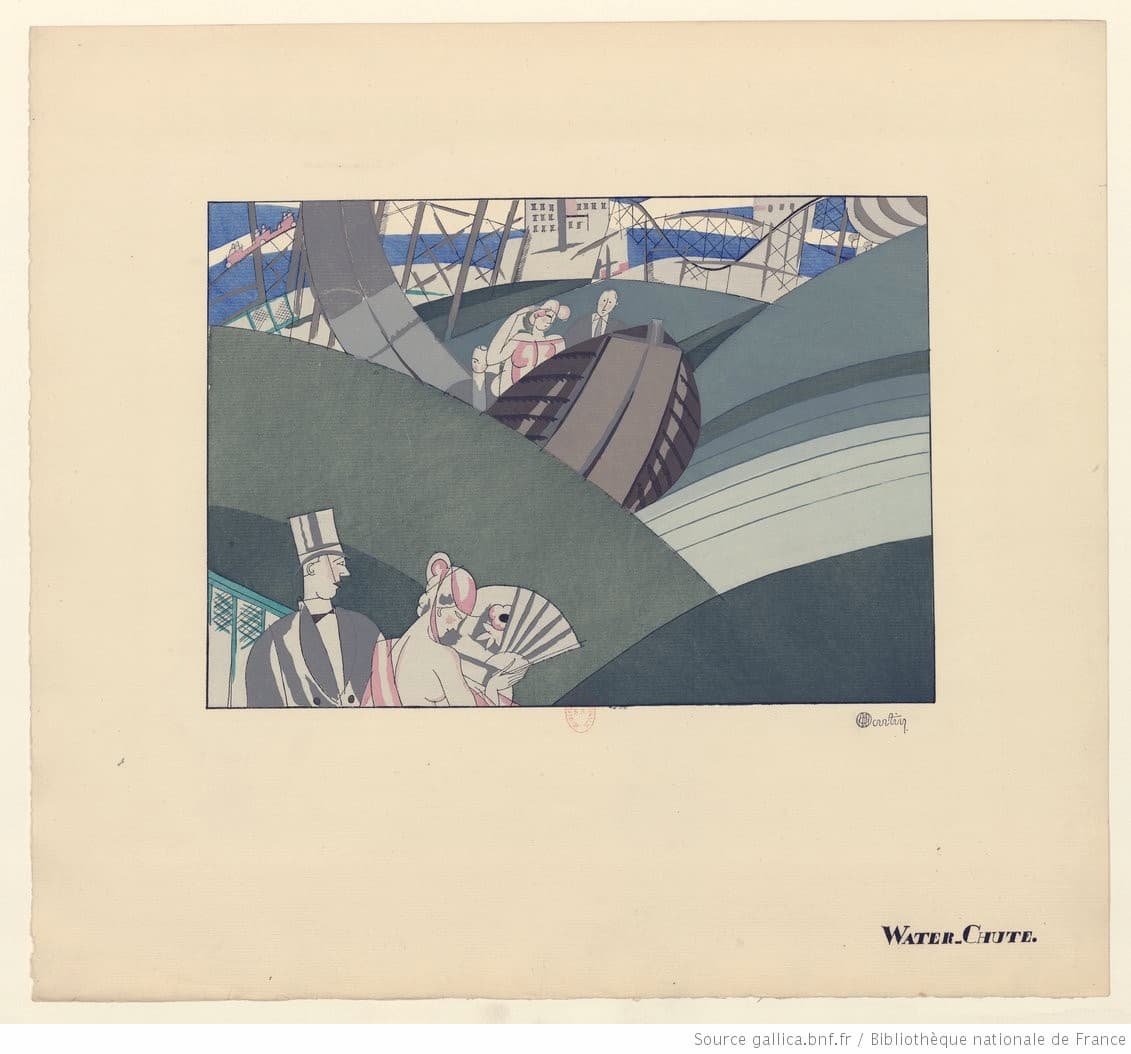

Charles Martin: Le Water-Chute, 1922

Erik Satie: Sports et Divertissements – XVI. Le Water-Chute (Olof Höher, piano)

Martin’s new design embraced cubism and was designed to be hand-coloured. The pochoir technique of hand colouring with stencils was applied by Jules Saudé. In the new illustrations, children are not to be seen. These are adults at play in the go-go 1920s. The title of the book Sports and divertissements was a common phrase used by the resorts of the time to attract the bright young things.

The new edition was ready to go to print in 1922.

At this point, Éditions de La Sirène intervened, saying that they had exclusive publishing rights to all of Satie’s music, ignoring the fact that Satie had signed his contract with Vogel 6 years before he signed the exclusive contract with La Sirène. This was resolved and, in late 1923, the work was finally published in 3 editions concurrently, numbering 900 copies.

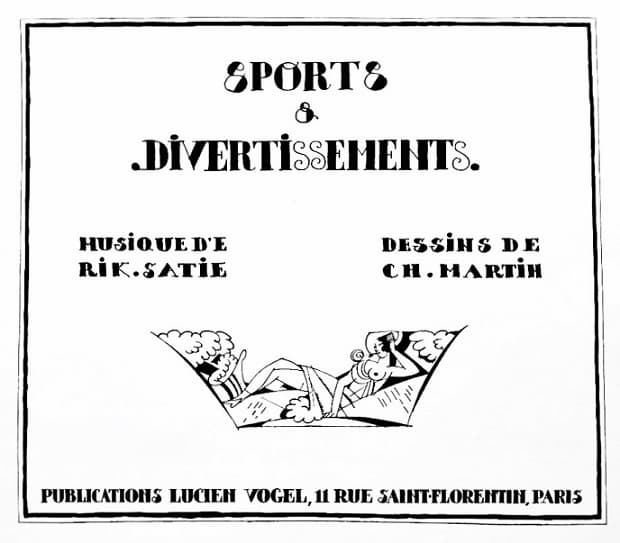

Title page of Erik Satie’s Sports et Divertissements

Copies 1-10 included both the 1914 copper plate and the 1922 coloured prints, Martin’s engraved table of contents, and engraved title pages for each piece with little vignettes. All 10 copies were given to Librairie Maynial, who had bought the edition when Vogel closed his company in 1916. One copy is currently in the Harvard University Library.

Copies 11-225 have Martin’s 1922 coloured plates and title pages.

Copies 226 to 900 have Martin’s title pages but only one coloured illustration, used as the frontispiece.

In all editions, Satie’s music appears in two colours. There are 20 illustrations, but 21 pieces of music, with Satie adding a ‘Choral Inappétissant’ (Unappetising Chorale) to the beginning because Satie had a fetish for things happening in sets of threes.

Erik Satie: Sports et Divertissements – I. Choral inappetissant (Olof Höher, piano)

Over time, we have changed our view on this book. It’s no longer an artist’s book by Charles Martin with associated piano music by Erik Satie, it’s become a delightful book of tunes and amusements by Eric Satie, and, oh yes, there’s some art. The next edition, in 1926, completely eliminated Martin’s art but also rendered Satie’s two-colour music only in black and white. This was reprinted in 1964. It wasn’t until 1982 that the two parts were reunited, but with Martin’s illustrations in black and white, with only the cover image giving a colour version of the originals.

Martin’s art and cubism have waned over the years, but we continue to be fascinated by the unique workings of Satie’s brain.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter