John Zorn’s Musical Work La Machine de l’être Inspired by Antonin Artaud

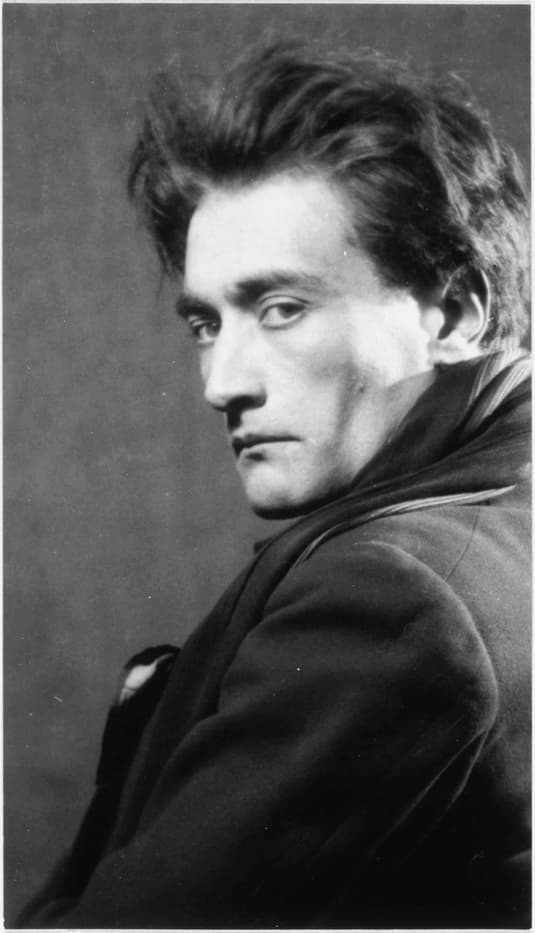

French actor and writer Antonin Artaud (1896–1948) tried to move early 20th-century theatre away from its reliance on text and towards more primal expressions of sound, movement, and light. Called Théâtre de la Cruauté (The Theatre of Cruelty), one of its ideas was that artists assault the senses of the audience. In the early 1920s, he was a member of the surrealist movement in Paris before being thrown out of the movement by André Breton for his ‘radical independence and his uncontrollable personality, perpetually in revolt’. In developing his new theatre, Artaud was influenced by non-Western performances he saw, such as that by a Balinese dance troupe he saw at the Paris Colonial Exhibition in 1931. He thought that ‘gestures, sounds, unusual scenery, and lighting [could] combine to form a language, superior to words…’.

Antonin Artaud

As with many post–WWI artists, Artaud was seeking ways to change the existing social structure that had permitted global warfare. By making the audience get around the language of thought and logic, he could prepare them to truly examine, both inside themselves and in society, the faults that ended up with society on the battleground.

The ‘cruelty’ of his theatre was not that of violence, but the physical shattering of a false reality. Text had been leading theatre for too long and Artaud wanted a new vocabulary ‘halfway between thought and gesture’. Beyond the story of a single individual or the actions of a group, Artaud wanted to plumb the subconscious to examine root causes. By exorcising those destructive feelings, the audience would reach through them to regain the joy normally suppressed by society.

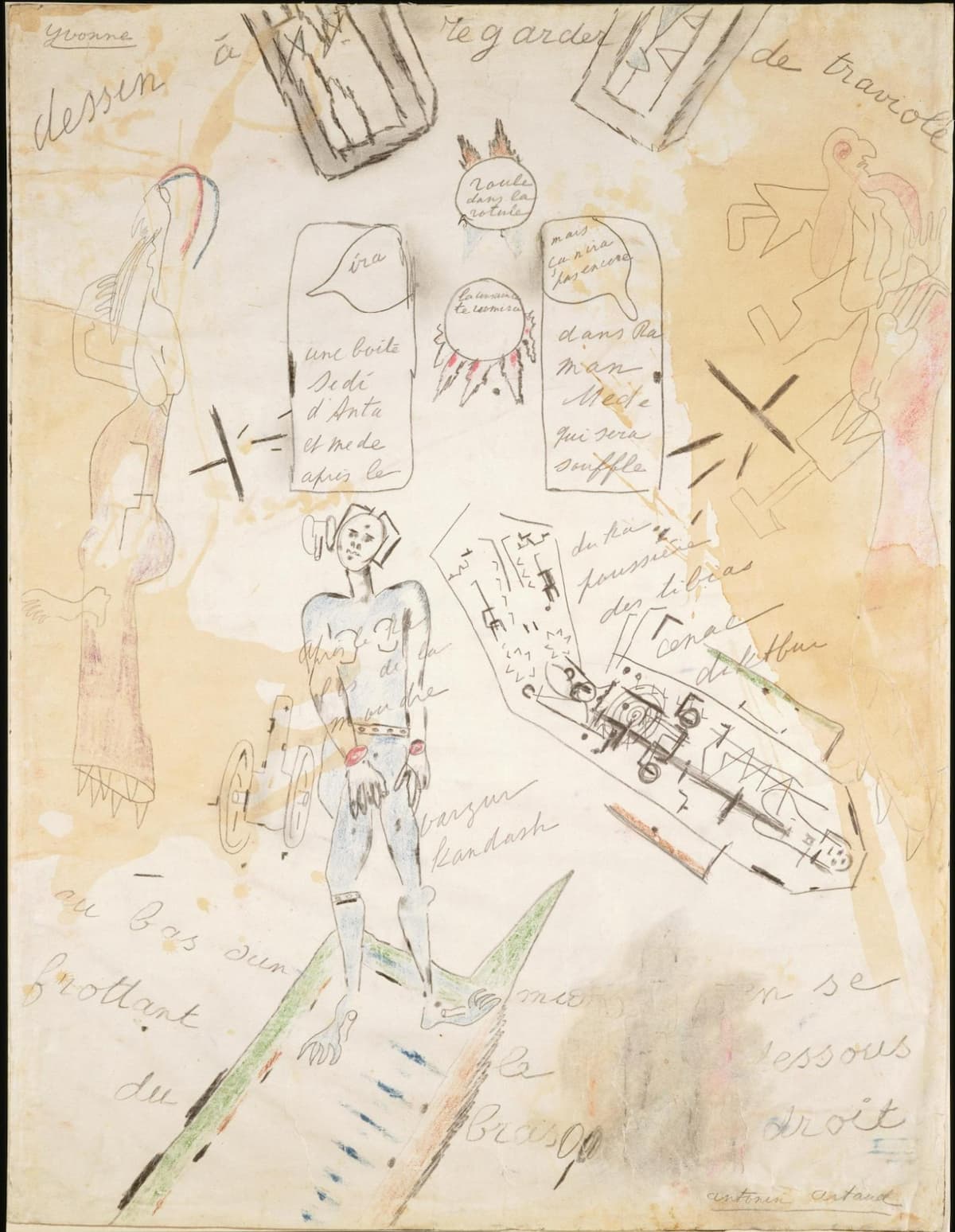

One of his 1946 drawings, with the title of La Machine de l’être ou Dessin à regarder de traviole (The Machine of Being or Drawing to Look at Askew), was an inspiration for New York composer John Zorn’s musical work La Machine de l’être.

Artaud: La Machine de l’être

Artaud had created this drawing and a number of others while at the psychiatric hospital at Rodez, where he was a patient from January 1945 through May 1946. Drawn in his schoolboy notebooks, the drawings were a ‘continuous flood of words and pictograms…’. Maxims, songs, glossolalia, scraps of sentences, shards of texts, scattered memories, interjections, invocations, endless lists of names and food…constitute the fragments of a textual work capable of “weeding out” his mind, eliminating the conventional “corseted language” that imprisons him…’. Here, writing and oral become visible. He wants his drawings to permit him ‘to rebuild a body with the bone of music of the soul’.

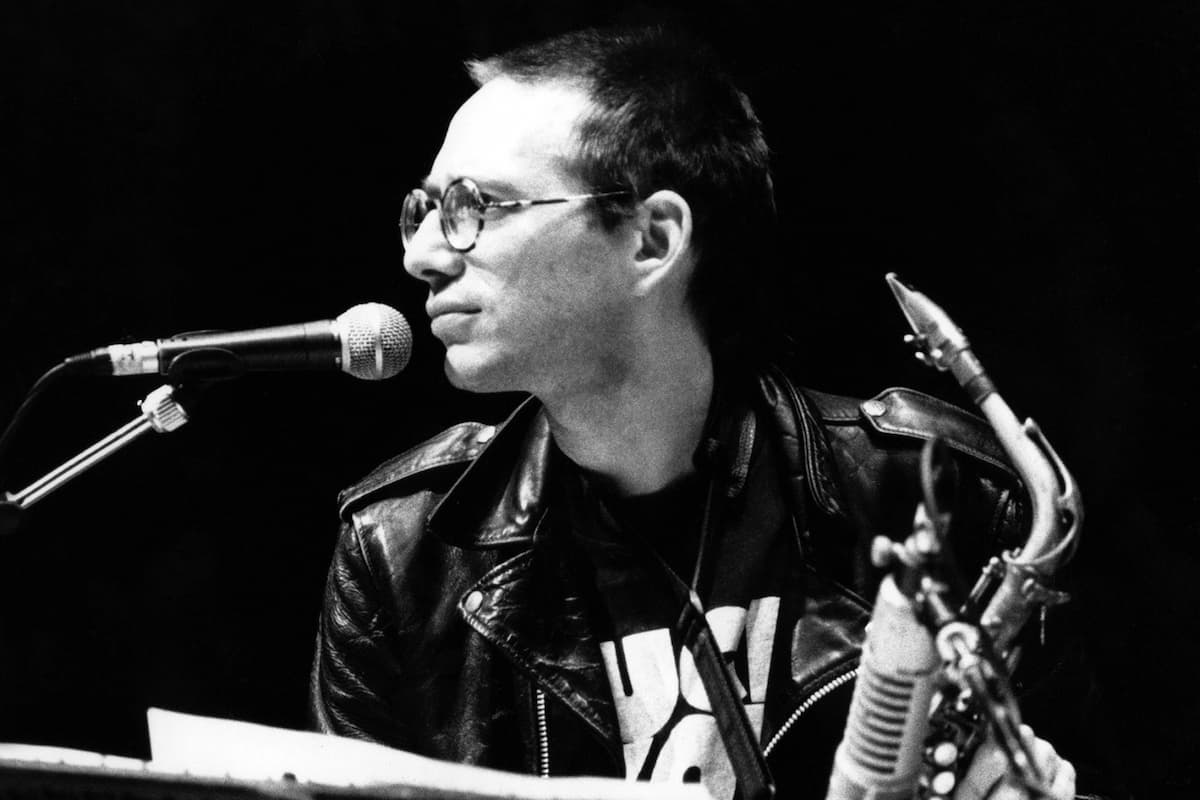

John Zorn

In keeping with Artaud’s philosophy that wanted to replace text with other ways of drawing out the human imagination, Zorn’s work is textless. Relying on the voice to express the emotions of the work, Zorn takes Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty out of the theatre and onto the concert stage. ‘… this work sets the stage for the voice as a kind of absolute presence – an indescribable medium for, or the unmediated expression of unadulterated feelings such as euphoria or madness. Without words or plot, focus is placed upon the voice and its boundless expressive potential’.

John Zorn: La Machine de l’être – I. tetème (Anu Komsi, soprano; Lahti Symphony Orchestra; Sakari Oramo, cond.)

John Zorn: La Machine de l’être – II. Le révelé (Anu Komsi, soprano; Lahti Symphony Orchestra; Sakari Oramo, cond.)

John Zorn: La Machine de l’être – III. Entremêles (Anu Komsi, soprano; Lahti Symphony Orchestra; Sakari Oramo, cond.)

Capturing Artaud’s ground-breaking philosophy in music pushes the audience to enter Artaud’s world. The text-less soprano line goes from the lyrical to the hysterical and all ranges in between. Silence has a role, particularly in the last movement, as much as sound.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter