Kenneth Fuchs: Cloud Slant

American artist Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) started appearing in American art galleries in the 1950s and continued her career for the next 60 years. Her field was abstract expressionism and her developments over her career changed modern art. Starting with inspiration from the splatter paintings of Jackson Pollock, she developed her own ‘painting on the floor’ technique that gradually drove her out of the centre of the canvas by using fluid shapes, abstract masses, and eventually, what was known as ‘colour field painting’.

Characterized by large, flat fields of colour, colour field painting became important in Frankenthaler’s work and is the first Frankenthaler’s painting that American composer Kenneth Fuchs uses in his concerto for orchestra, Cloud Slant.

Kenneth Fuchs (b. 1956) was inspired by Frankenthaler’s work early in his career and he has composed, to date, six pieces based on her paintings. He first discovered Frankenthaler’s work while a student at Juilliard in the 1980s, after seeing it in a documentary. When he saw her work in person at an exhibition in December 1983, he felt an instant affinity with her work. He saw her painting Out of the Dark and made it part of his own work of that title, based on her large paintings: Heart of November, Out of the Dark, and Summer Banner. The suite was originally written for chamber ensemble and then revised as work for chamber orchestra.

The latest Frankenthaler inspired work is Cloud Slant, begun in the 1990s and then abandoned until 2019 when Fuchs resumed work on it.

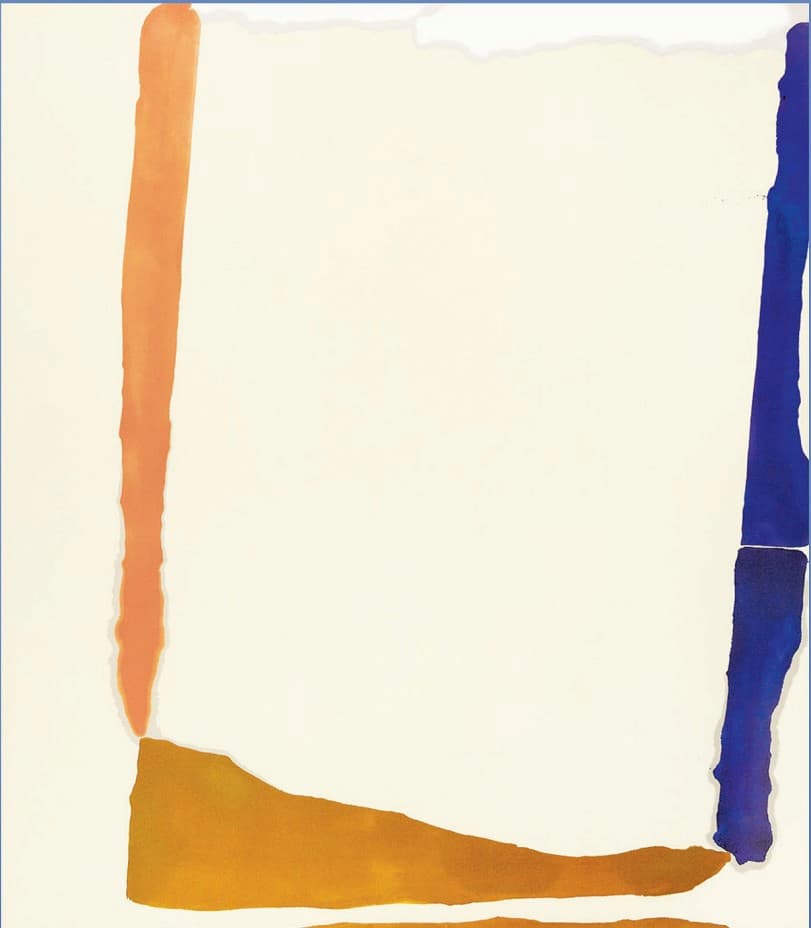

Inspired by three different works, Fuchs has written a three-movement work that follows the paintings in chronological order. In her 1966 painting Blue-Fall, Frankenthaler cascades a vivid blue down onto a gold-yellow stripe at the base.

Frankenthaler: Blue-Fall, 1966 (Milwaukee Art Museum)

In his music, the first movement starts with what the composer calls an ‘aural frisson’, repeated twice to start the work.

Kenneth Fuchs: Cloud Slant – I. Blue Fall (Sinfonia of London; John Wilson, cond.)

The music was created in three sections, with alternating tempos – sometimes the notes, like the paint, rush in a torrent over the edge, and, in other sections, seem to lie like a limpid pool or just meander.

Although Fuchs calls for a standard orchestra, it has all the extra instruments, too: piccolo, English horn, high E flat and bass clarinets, an alto saxophone, contrabassoon, a quintet of percussionists, plus harp, piano, and celesta. This is Fuchs’ colour field, in a sense. The orchestration doesn’t pick out individual instruments but gives us washes of instrumental colour in a section.

Frankethaler’s Flood, dating from 1967 shows a distinctive change from the year before Blue-Fall. Now the oil paint has been thinned to the consistency of watercolour. Like Pollock, she placed this canvas on the flood and poured out her colours, rarely resorting to a brush. We’re given a simplified landscape: sky cloud, mountain, forest, and water, with the additional emotional load created by the colours used: zones of oranges, pinks, green, and purple. Frankenthaler said about this work: ‘I think of my pictures as explosive landscapes, worlds, and distances, held on a flat surface’.

Frankenthaler: Flood, 1967 (Whitney Museum of American Art)

Just as Frankenthaler’s painting draws the eye to the light at the top before falling to the darkness at the bottom, Fuchs’ sound starts calm and light but darkens as it develops. The aural frisson of the first movement reappears in an extended form before the strings take over. A horn melody evolves into trumpet fanfare before slowing at the end, led by the woodwinds.

Kenneth Fuchs: Cloud Slant – II. Flood (Sinfonia of London; John Wilson, cond.)

The final painting gives Fuchs’ work its title: Cloud Slant. Critics see this work as a critical breakthrough in her development. She’s moved the painting off the canvas by tilting the image and it seems to float off the edge. There’s also the implication of a mirror image at the bottom of the painting, with the repeated brown colour. Although these three paintings are only separated by a year each, tremendous changes in both her painting technique, the material used, and even the concept of what goes on the canvas can be seen.

Frankenthaler: Cloud Slant, 1968 (Private Collection)

Fuchs’ final movement is infused with the same kind of light in Frankenthaler’s painting: it begins with a gentle opening and then, as befits a concerto for orchestra, solo instruments make their appearance. Like the image, the movement flows but it’s an irresistible flow.

Kenneth Fuchs: Cloud Slant – III. Cloud Slant (Sinfonia of London; John Wilson, cond.)

By taking 20 years between inception and completion, Fuchs has given us the sonic equivalent of taking a step back, taking a retrospective examination of a painter’s output, and giving us a work that, as a whole, is both a re-examination and a reflection.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter