Virko Baley: Sculptured Birds

For his work for clarinet and piano, Sculptured Birds, Ukrainian-American composer Virko Baley (b 1938) chose four modern artists for his four movements, beginning in 1978 and continuing in 1982 through 1984.

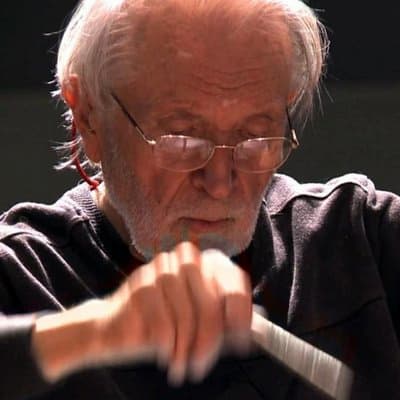

Virko Baley

The Sculptured Birds suite began in 1978 with a single movement, The Jurassic Bird, before the additional movements were added at the request of clarinetist William Powell. The subject of the four movements, beyond birds, is that of flight.

David Smith (1906–1965) took abstract expressionism to sculpting and painting. He’s best known for his large street abstract sculptures. Traditional metal sculptures were done by bronze casting, however, Smith moved to direct welding of steel and other metals, applying a painterly style to his sculpture creations. He saw the advantage of sculpture over painting that sculpture had a third dimension denied to 2-dimensional painting.

His work from 1945, Jurassic Bird, shows, in his words, ‘Three levels of the Jurassic Age. 1. Underground, two lung fish uphold the earth. 2. Emerging level—part cannon—part pleosoris, where the cannon should have stayed. 3. Aerial Form—Skeleton of Jurassic made as bow of ship with ribs located as slaves in a galley ship.’

David Smith: Jurassic Bird, 1945 (Private collection)

(Photo by David Heald)

In his music, Baley wants the first movement to be ‘a remembrance of the precursor of flight’. The composer notes that ‘fragments of that memory are lamented in the piano part, as a 2-voice chorale in B minor (based on the old “Dies irae” chant), preceded by a short percussive chord which is used as an invocation to remembrance.

Virko Baley: Sculptured Birds – I. Jurassic Bird (after David Smith) (William Powell, clarinet; Virko Baley, piano)

The second movement, The Eagle, is based on a sculpture by Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964). Ukrainian-born Archipenko moved to Paris in 1908 and in 1910 discovered cubism. Four of his cubist sculptures were part of the famous Armory Show in New York in 1913. He had been one of the first to create in the cubist style, following Pablo Picasso and the French-Hungarian sculptor Joseph Csaky, exhibiting at the Salon des Indépendants and Salon d’Automne, in 1910 and 1911, held in Paris.

No work entitled ‘The Eagle’ appears in Archipenko’s catalogue.

In his second movement, Baley depicts the Slavic melos, melodrama, and the screams of outrage that seem to be an explicit feature of the Slavic aesthetic profile. The clarinet comes to the fore in this movement, with florid and extreme melodic passagework over an extended piano cadenza until both performers seem to collapse from exhaustion.

Virko Baley: Sculptured Birds – II. The Eagle (after Alexander Archipenko) (William Powell, clarinet; Virko Baley, piano)

Romanian artist Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957) made his career in France and was an important foundation in the development of modern sculpture. His emphasis on symbolic allusions and clean lines led him to create works that were about the essence of an idea rather than merely copying appearances.

Bird in Space was one of his most famous series. Abstract shapes caught the idea of a bird in flight. Starting with the series of birds called Măiastra, which were recognisable as birds but smoothed out, his next step in creating his Birds in Space was to remove all detail.

Brâncuși: Bird in Space, between 1932 and 1940 (New York: Guggenheim Museum)

This work is not about the bird, but about the bird in flight. The pointed top is all that remains of the beak, while the bottom indent defines the tail.

Baley described his third movement, Bird in Glide, as an activation of Brâncuși’s Bird in Space. The essential ‘birdness’ of the sculpture is taken by the clarinet, with the piano as its earthbound support. In the clarinet part, Baley has the performer extend from the basic chordal foundation into the overtones, growing out into space.

Virko Baley: Sculptured Birds – III. Bird in Glide (after Constantin Brancusi) (William Powell, clarinet; Virko Baley, piano)

Two different birds inspired the final movement. The first was Max Ernst’s collage The Chinese Nightingale and the second Casanova’s bird in Fellin’s film Casanova.

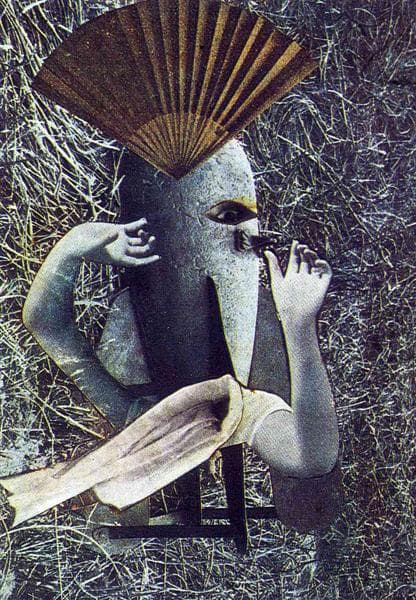

Max Ernst: The Chinese Nightingale, 1920

Fellini: Casanova: Casanova’s bird statue, 1976

In his work in 1919 and 1920, Ernst used images from military publications to create his collages. The Chinese Nightingale started with a picture of an English bomb lying on the grass. Arms, a flowing cloth, a fan and an eye were added, and our bird appears. The story of the Chinese Nightingale is familiar from Hans Christian Andersen’s story The Nightingale, where the Chinese emperor is given a nightingale, but which leaves him when he likes his mechanical replacement better. When the emperor is dying and his mechanical toy no longer works, the nightingale returns to restore the emperor’s health and to drive death away.

Ernst, caught up in the horrors of the first world war, where he was in the artillery, brought the idea of the collision of bodies and machines together. Perhaps we shouldn’t look at this as arms added to a bomb, but what’s left after the bomb hits.

Casanova’s mechanical bird statue, which moves with a frenetic pumping motion and has its own strange music, brings a compulsive and mechanical side to some of Baley’s setting.

Virko Baley: Sculptured Birds – IV. The Chinese Nightingale (after Max Ernst) (William Powell, clarinet; Virko Baley, piano)

Just as each of the artists defined a time, so Baley’s separate movements try to set them to music. From references to traditional chants for the dead to extended clarinet flights above the piano, Baley takes the idea of flight into music into a new sound world.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter