Ellen Taaffe Zwilich: Images, for two pianos and orchestra

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich

American composer Ellen Taaffe Zwilich responded to a commission from the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) with a work that reflected the contents of the museum’s collection. Written for the opening of their permanent gallery in 1986, the work Images, for two pianos and orchestra, was given its premiere with Leeanne Rees and Stephanie Stoyanoff as pianists and with Fabio Mechetti leading the National Symphony Orchestra.

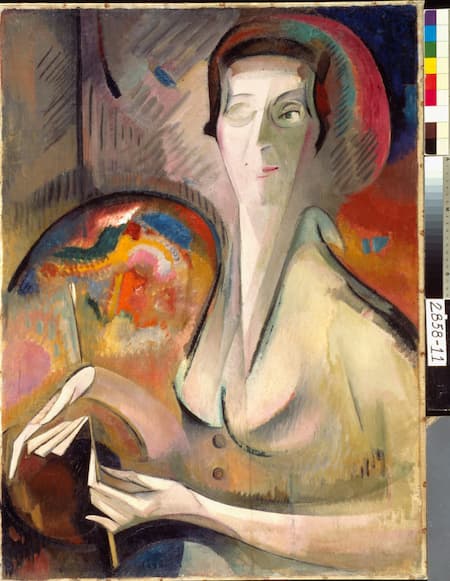

She opens with a self-portrait by Swiss painter Alice Bailly (1872-1938). The work is unusual in its presentation of a traditional artist’s self-portrait, combining a number of different art styles in one work: Cubism, Fauvism, Dadaism, and Italian Futurism. The colours are dissonant, yet the shapes are geometric and organic, some elements are carefully delineated while the entire right side of her face is painted out. In the music, the same mix of organic development mixed with dissonance holds sway. Zwilich saw the artist as creating a ‘(literally) self-effacing portrait’.

Alice Bailly: Self-Portrait (1917) (NMWA)

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich: Images – I. Opening (Read Gainsford and Heidi Louise Williams, pianos; Florida State University Symphony Orchestra; Alexander Jiménez, cond.)

Movement II uses La Poupée Abandonnée (The Abandoned Doll) by Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938) as its inspiration. French painter Valadon grew up in Paris and a fall from a trapeze when she was a circus performer led her to a new profession. From 1880 to 1893, she modelled for the important Parisian painters of the time, including Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec, and learned from her friend Degas about drawing and etching techniques. As a rare woman involved in the late 19th century art world, Valadon brought women’s ideas to the fore in many of her paintings. La Poupée Abandonnée shows us the transition of a young girl from child to adult. Her doll, with its red hair bow, lies discarded on the floor, and she looks to the mirror to show her the development of her body, and her own red hair bow. Her sharp naked definition will change in time to that of her mother seated next to her – covered in a shapeless black gown and grown heavy with life. With its use of colour and staging in a bedroom, the picture is almost another version of Van Gogh’s The Bedroom, which also has a red coverlet on a bed in a room with a wooden floor. Zwilich’s music moves us up from the floor to the bed, with a melancholy edge that may actually reflect not the girl but the thought of her mother as she dries off the no-longer-child with a towel. The music still has some elements of child’s play and rhymes, but it’s overlaid with darker colours.

Suzanne Valadon: La Poupée Abandonnée (1921) (NMWA)

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich: Images – II. La Poupée Abandonée (Read Gainsford and Heidi Louise Williams, pianos; Florida State University Symphony Orchestra; Alexander Jiménez, cond.)

Movement three, Iris, Tulips, Jonquils and Crocuses, brings us into the late 20th century. The work, by American artist Alma Woodsey Thomas, was part of her experimentation with abstract painting. Her early works were realistic and once she retired from teaching in 1959, she moved to abstract painting and in doing so, found her style. Thomas was the first African-American woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art and she was an important role model in modern art for women and older artists. The painting presents the flower colors in a mosaic-like vertical striping. In her movement, Zwilich has the pianists hammer at a single pitch while the orchestra comments in the background.

Alma Woodsey Thomas: Iris, Tulips, Jonquils and Crocuses (1969) (NMWA)

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich: Images – III. Iris, Tulips, Jonquils and Crocuses (Read Gainsford and Heidi Louise Williams, pianos; Florida State University Symphony Orchestra; Alexander Jiménez, cond.)

Elaine de Kooning’s Bacchus #3 (1978) gradually, upon study, resolves from pure abstraction to a figure group. She captures the twisting form that was the traditional representation of Bacchus, the god of wine, adding in his Bacchante followers, who gather around their god of drinking. The greys, blues, and purples of the interwoven bodies is set off by the greens and yellows of their pastoral setting. Zwilich conveys the twisting and intertwining of the bodies, focused on their inebriation, while brass convey, perhaps, the temporary nature of all this fun.

Elaine de Kooning: Bacchus #3 (1978) (NMWA)

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich: Images – IV. Bacchus No. 3 (Read Gainsford and Heidi Louise Williams, pianos; Florida State University Symphony Orchestra; Alexander Jiménez, cond.)

The work closes with the most abstract of all the works in this collection: Helen Frankenthaler’s Spiritualist. A second-generation Abstract Expressionist, Frankenthaler followed artists such as Jackson Pollock in painting while her canvas lay on the ground. In this work, the canvas is untreated and the paint has the effect of staining, rather than sitting on top of the material. Colours flow and cross by chance and Frankenthaler does little to manipulate them. She creates different levels of texture in the painting; the untreated canvas comes through the lightly applied paint and then on top, she’s added short black lines to extend or define areas. In her music, Zwilich begins with a solemn opening in the strings and then adds percussion for definition. The work as a whole cycles back to the beginning with quotations from the opening movement appearing again.

Helen Frankenthaler: Spiritualist (1973) (NMWA)

Ellen Taaffe Zwilich: Images – V. Spiritualist (Read Gainsford and Heidi Louise Williams, pianos; Florida State University Symphony Orchestra; Alexander Jiménez, cond.)

In what is a virtual history of women’s art over the 20th century, Images does not match those works with music of the same time periods. This is a century’s worth of art viewed through a late–20th-century viewpoint. The instrumentation of 2 pianos is unusual, particularly in that they are often heard as one massive keyboard, rather than as two pianos fighting for supremacy. The choice of art by Swiss, French, and American women artists, both black and white, is a measure of how far 20th century art had come from being the sole province of white men, as well as a reflection of the meaning of the Museum itself.

The National Museum of Woman in the Arts, which began in 1981 and opened its doors in 1987, is the only major museum in the world solely dedicated to championing women through the arts. The museum addresses the gender imbalance in the presentation of art by researching and exhibiting important women artists of the past while promoting women artists working today.

Each of these paintings was a gift of Wallace F. and Wilhelmina Cole Holladay to the Museum, founders of the Museum, and Zwilich’s work is dedicated to Wilhelmina Cole Holladay.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter