To start with, I have to confess that although I have long been fond of Schubert, he hasn’t been among my “favourites” (if such a term is appropriate). Somehow, I have found a barrier between Schubert and me that prevented me from understanding the true intent of his music until recently.

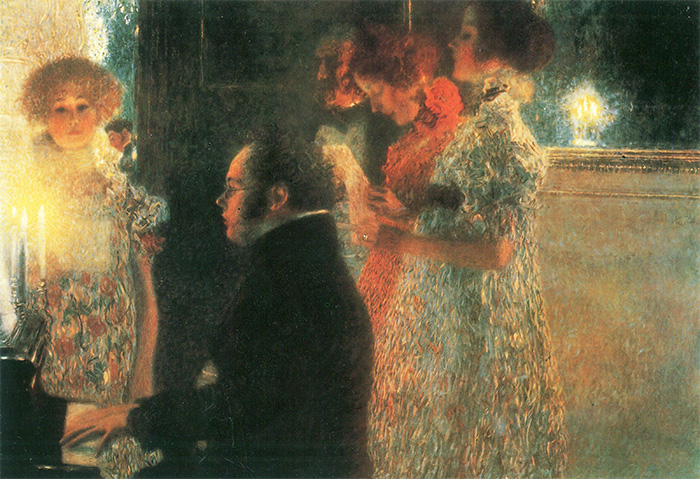

Schubert at the Piano – Gustav Klimt (1899)

Schubert is probably the only composer who can create music that is even more heart-wrenching and disturbing in major keys than in minor keys. An example I would immediately think of would be his Klavierstücke No. 2 in E-flat major. Starting with a gentle and intimate atmosphere, it then transits into the tumultuous first trio and later the more poignant second trio in A-flat minor. There’s a moment where the music suddenly detours into A-flat major (a dominant seventh technically) for merely one bar and then returns to the original tonality. Compare 6:36 and 9:07 in the recording below – this never fails to give me goosebumps, as if there’s finally a gleam of hope, but it’s extinguished in a matter of seconds.

Franz Schubert: Klavierstücke, D. 946 No. 2 in E-Flat Major (Grigory Sokolov, piano)

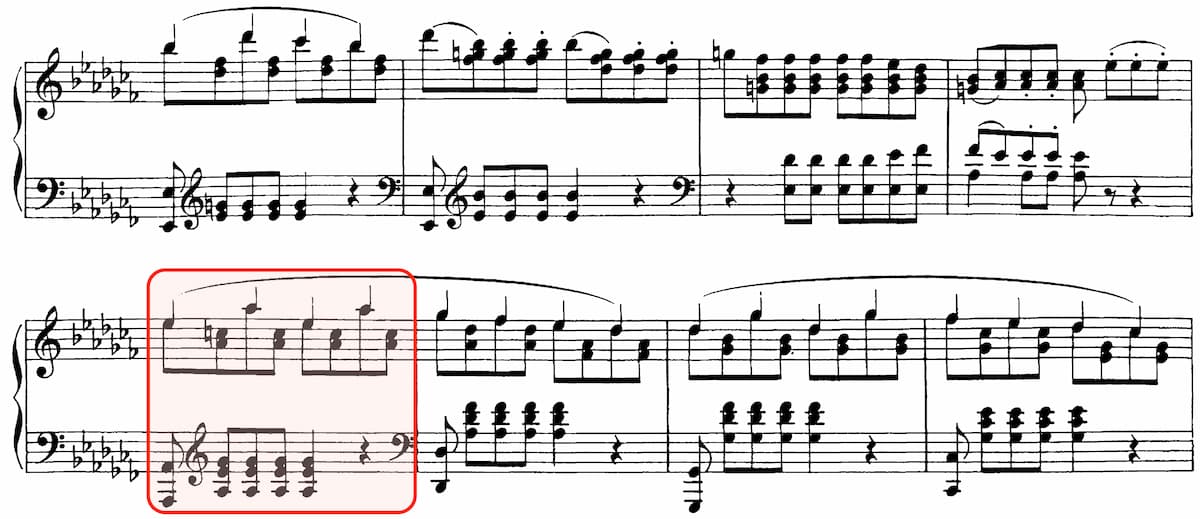

Figure 1

The bar highlighted in blue appears for the first time in A-flat minor.

Figure 2

This time it is in A-flat major but returns to the original tonality after one bar.

Schubert is always a complex figure, with his music oozing so much nostalgia, hope, loss, grief, frustration, and many more. All these emotions are what make human beings fragile, but at the same time, what make us human. His music is often suffused with bittersweetness, in the sense that the apparently more joyous moments are, in fact, reminiscences of the unattainable past, while the music often draws us back to the darker side as if an interrupted dream.

Paul Lewis illuminated Schubert’s emotional landscape with an uncompromising interpretation of his sonatas in Hong Kong. In the Sonata in A major, D.664, I experienced embracing warmth, a sense of relief despite tinges of sorrow, and the imagery of rustic scenes, with the third movement full of buoyancy and a dancing pulse. On the other hand, Schubert’s neuroses and anguish fully came through in the Sonata in A minor, D. 845, coupled with such abandon and immensely white-hot passion from Lewis.

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 13 in A Major, Op. 120, D. 664 – III. Allegro (Paul Lewis, piano)

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 16 in A Minor, Op. 42, D. 845 – I. Moderato (Paul Lewis, piano)

In my interview with Paul Lewis, he aptly described the “lack of resolution” in Schubert’s music, with which I greatly sympathise. Schubert often brings up conflicts without offering an answer, leaving us in a state of ambivalence. That’s something that makes his music close to my heart – after all, not everything in the world has or requires a resolution or an answer. Unlike Beethoven, Schubert accepted his fate as it was, and such an acceptance is most evident in his late sonatas.

Franz Schubert: Piano Sonata No. 21 in B-Flat Major, D. 960 – IV. Allegro ma non troppo (Radu Lupu, piano)

Chopin once said, ‘Bach is an astronomer, discovering the most marvellous stars. Beethoven challenges the universe. I only try to express the soul and the heart of man.’ We can perhaps draw a parallel here. Schubert neither explored the topics of divinity and religion nor attempted to fight against his fate. Instead, it is all about the deepest, often ineffable human emotions, which is probably why listening to his music can provoke such a probing ache.

As with Schubert’s music, this piece of musing (or nonsensical mumbling for some) shall come to an end without a resolution, which is paradoxically yet to be discovered in his music per se.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Franz Schubert: 6 Moments musicaux, Op. 94, D. 780 – No. 6 in A-Flat Major: Allegretto (Pauul Lewis, piano)

Anson you need to listen to András Schiff play Schubert on fortepiano. This will revolutionise your listening. The Sokolov is wonderful but the lags in tempo are annoying. Schubert does not need an iota of feeling added — the emotion is intrinsic to the music when obeyed.

When we feel a piece of music intensively, it is natural to assume that the emotions we feel motivated the composer as he wrote the music. This is absurd. We have no way of knowing the mood of a composer when he writes a piece of music or his feelings as he goes about the rest of his life. Music is a language and each piece is created by the composer, using the same musical tones as all other composers. Music does not express emotion; it EVOKES IT! The degree to which it evokes it cries with each composer. Even second or third rate compositions can evoke emotions (I call these “cheap thrills”). That Beethoven was able to inject humor in his music even when he was deaf, or that Brahms can give us exquisite schmaltz despite his being the most rational, organized and disciplined composer who demanded the highest craftsmanship for himself (and foreswore marriage in order to put his music first) is indicative of the fact that music is an intellectual craft first and foremost, not the gypsy violin music played at your table in a restaurant. Nor does music convey political leanings or social conditions, whether it is a “peace” oratorio or memorial to someone’s death. It affects us

deeply but our emotional response is evoked by the content and form of the piece. For all we know Schubert wrote Die Erlkonig

while he was having a beer in a bierstube.