In folklore, mythical creatures fulfill the worlds our imaginations create: trolls in the underworld, mermaids in the water, and unicorns in the forests and fields.

We’ll start in the underworld. One of the most famous trolls in music comes from Grieg’s Peer Gynt, when our hero finds himself in the Hall of the Mountain King.

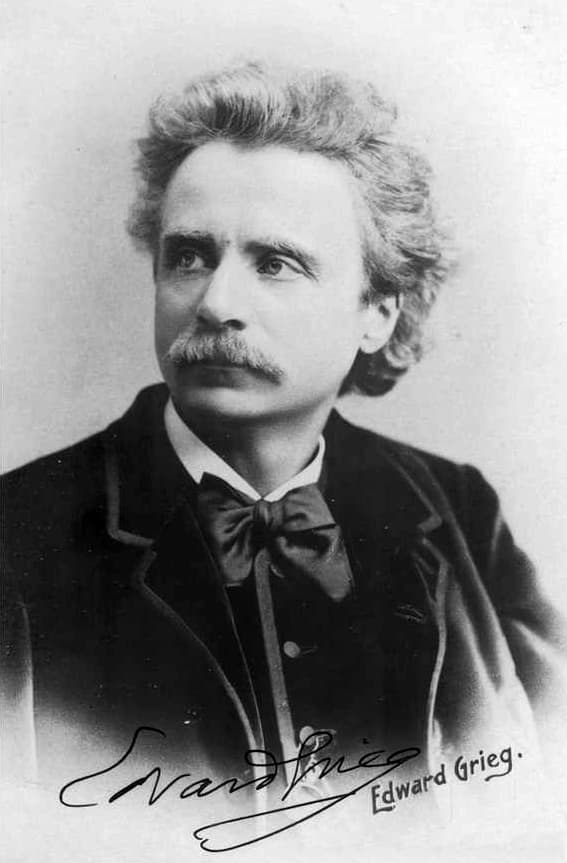

Edvard Grieg, carte de visite, 1889

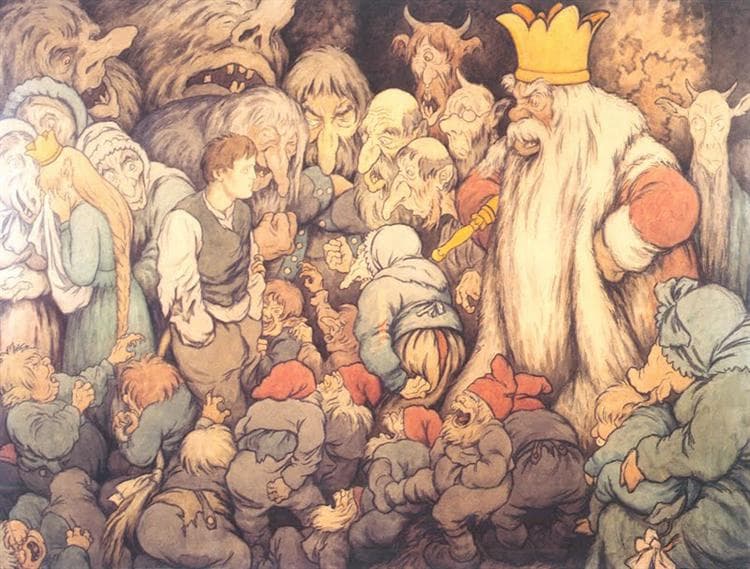

As the incidental music for Ibsen’s play, the music has menace. You have to imagine yourself in the darkened theatre, curtain down, as the music starts its long climb from the lowest voices to end in a wild climax. When it was first on stage in 1876, it caused consternation and it was seen as shocking when the curtain came up on a scene of the underworld with swarming trolls.

When he set the music for Peer Gynt, Grieg was in somewhat of a quandary, as he felt that the story was essentially ‘unmusical’ and that the best he could do was to concentrate on external effects. Grieg wrote that ‘the musical element in the trolls’ realm was pure parody so I came up with something for the Mountain King’s hall that I literally can’t bear to listen to: it reeks of cow pies, exaggerated Norwegian provincialism and trollish selfishness!’. We’ll let Peer have the last word on this: ‘Both the dancing and the playing – may the cat claw my tongue – were utterly delightful’. Grieg did not attend the premiere for fear of the audience’s reaction – it was only gradually that he warmed to the world he had created.

Theodor Severin Kittelsen: I Dovregubbens hall (In the Hall of the Mountain King), 1890

Edvard Grieg: Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 – IV. I Dovregubbens hall (In the Hall of the Mountain King) (Malmö Symphony Orchestra; Bjarte Engeset, cond.)

Finnish composer Heino Kaski (1885-1957) wrote lovely miniatures, including this one of trolls. The work has been described as ‘Grieg-like’ but these are much less menacing than Grieg’s mountain dwellers.

Heino Kaski

Heino Kaski: Vuorenpeikkojen iltasoitto (Trolls Playing Taps), Op. 15, No. 1 (Risto Lauriala, piano)

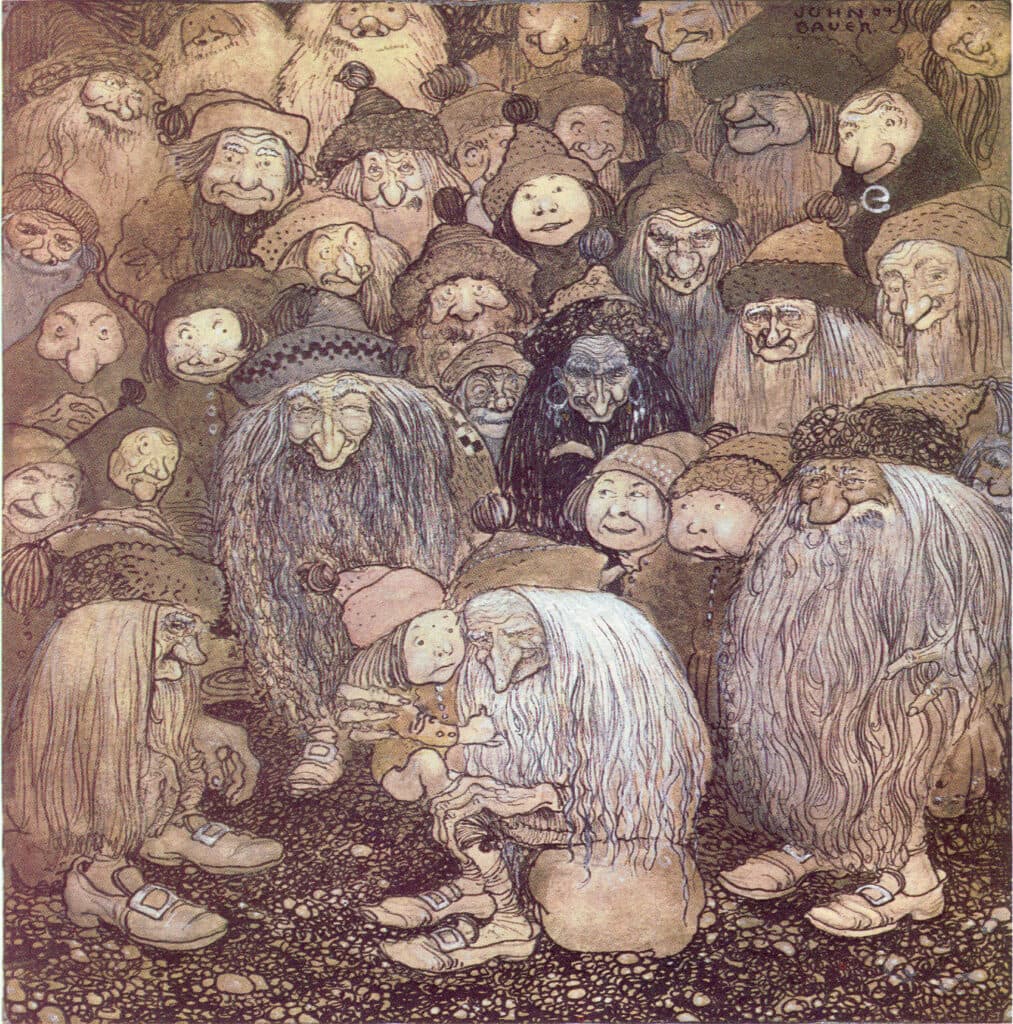

Rackham: In the Hall of the Mountain King

In his lyric pieces, Grieg wrote another troll piece, this time the March of the Trolls, which seems to keep part of their metal-working or digging activities as part of the initial section of music. It’s the lyrical middle section that gives us another view of the troll life.

Edvard Grieg: Lyric Pieces Op. 54, No. 3 – March of the Trolls (Balázs Szokolay, piano)

Swedish composer Hugo Alfvén (1892–1960) made his venture into the troll world in his 1923 ballet Bergakungen (The Mountain King). Unlike Grieg, who found little intrinsically musical in Peer Gynt, Alfvén found that the setting gave him great latitude to be creative.

It was so much fun to write that ballet because I had the opportunity to depict nature in all its different moods in the enchanted forest…. I got the opportunity to depict the hall of the Mountain King. … I never had so much pleasure as when I wrote this work.

In the third act, we have the trolls’ dance.

Hugo Alfvén

Hugo Alfvén: Bergakungen (The Mountain King), Op. 37 – Act III Scene 1 – Trollens andra dans (The second dance of the trolls) (Malmö Symphony Orchestra; Stig Rybrant, cond.)

Later in the third act, as the troll Humpe faces down the herdsman after he has attempted to steal away the herdsmaid, he’s confronted by an unexpected sword in the herdsman’s hand – his reaction is a unique sound in the orchestra. You’ll hear it at 01:37, where the four clarinetists play only their mouthpieces, having removed the rest of the instrument to the side. Alfvén said he thought this was a very troll-like sound. The conductor at the premiere said Wagner would be jealous that he hadn’t found that sound first!

John Bauer: The Trolls and the Gnome Boy, 1909

Hugo Alfvén: Bergakungen (The Mountain King), Op. 37 – Act III Scene 2 – Humpe forsoker rova bort vallflickan (Humpe tries to steal the herdsmaid away) (Malmö Symphony Orchestra; Stig Rybrant, cond.)

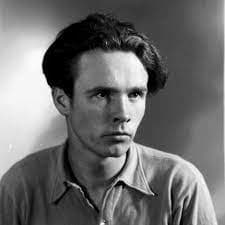

Norwegian composer Geirr Tveitt (1908–1981) studied in Germany at the Leipzig Conservatory and in Paris with Honegger and Villa-Lobos as well as Nadia Boulanger before heading to Vienna to work with Egon Wellesz, a former pupil of Schoenberg, giving him one of the most diverse backgrounds of his contemporaries. He was the center of a strong nationalist movement in Norway but became marginalized by the Norwegian musical community because of his views. A fire at his house destroyed some 300 works, an estimated 80% of his compositions, and he went into an alcoholic decline that eventually killed him.

One of his greatest works was his Opus 151 collection of folk tunes from the Hardanger district. Tveitt settled in the area in 1940 and worked with the local folk musicians. Taking traditional songs and imbuing them with his musical knowledge of the avant-garde, he was able to not only preserve the melodies but also invoke the ‘atmosphere, mood and scenery in which it belonged’.

Suite No. 5 of the 100 Folk-Tunes from Hardanger is entitled Troll Tunes and Tveitt brings out both the underground trolls and the hidden forces of the nature around them. The first piece, Trollstemt hardingfela (Troll-tuned Hardanger fiddle), refers to one of the many different tunings of local hardanger fiddle – troll tuning permits ‘numerous very mournful notes’.

Geirr Tveitt

Geirr Tveitt: 100 Folk-tunes from Hardanger, Suite No. 5 – Troll tunes, Op. 151: 61. Trollstemt hardingfela (Troll-tuned Hardanger fiddle) (Stavanger Symphony Orchestra; Ole Kristian Ruud, cond.)

Trolls come from Nordic folklore and in the music above, we’ve seen how Norwegian, Finnish, and Swedish composers have taken them as subjects. In the older Norse sources, trolls live in isolated rocky areas as families and ‘are rarely helpful to human beings’. In Scandinavian folklore, they are considered dangerous to humans – their appearance may be ugly and hairy, or they may look exactly like humans.

As night or underground creatures, they turn to stone on contact with sunlight. This idea was used by J.R.R. Tolkien in The Hobbit where Bilbo Baggins saves his company by delaying trolls until dawn petrifies them. And, as another kind of Scandinavian troll, we always have the Moomins.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter