Ivan Mazepa

Lord Byron’s narrative poem from 1819, Mazeppa, was one of the great influential pieces of Romantic writing. Plays, musical pieces, operas, novels, even circus performances were based on the work.

The poem tells the legend of Ivan Mazepa (1639-1709). Mazepa is caught in a love affair with a Polish countess. When her husband discovers them, he binds the naked hero to a wild horse and lets it loose, to take the errant lover back to the Ukraine, his homeland. The majority of the poem is about Mazeppa’s endurance and suffering as he struggles to free himself. The story is told in flashback by Mazeppa to King Charles XII of Sweden after a defeat by the Russian forces. The King admires Mazeppa’s skill with horses and Mazeppa tells him how he learned his horsemanship.

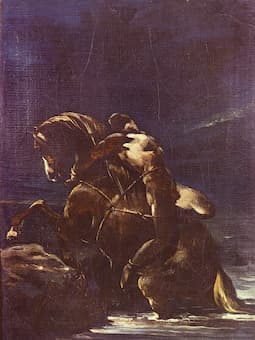

Géricault: Mazeppa, ca. 1823

Byron’s poem used Voltaire’s biography of Charles XII (1731) as his source for the story, but the story appears to have been in circulation even before Voltaire took it up. Byron wrote his poem in 1818-1819 and it’s been described as treading a line between ‘high emotion and lighter irony.’ Bryon presents the story but doesn’t indicate if he finds Mazeppa a hero or not. Some find Mazeppa’s story in keeping with those told about their youth by tiresome old men and other’s find the story of the wild ride the point of transformation of Mazeppa from a careless lover to a man who can control his passions.

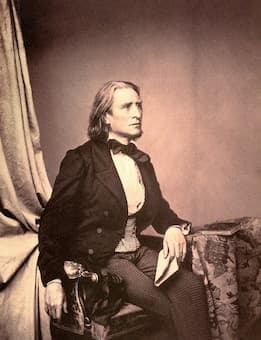

Franz Liszt (1858)

The story was taken up by the French writer Victor Hugo in his poetry collection on liberty, Les Orientales (The Orientals), where he divides the story into two parts: first is the story of Mazeppa and the horse, which he rides until its death, and the second part is about his spiritual process of getting back to life. The latter is taken as an allegory of the search for a creative life.

For artists who encountered his story, it served as a well of inspiration. Romantic period painters often had horses as their subjects and Mazeppa’s story was taken up by Franz Liszt as the subject for his symphonic poem of the same name.

Oskar Fried (left) in 1928 celebrating Maurice Ravel’s birthday, joined by singer Éva Gauthier, composer and violinist Manoah Leide-Tedesco, with George Gershwin at the right and Ravel at the piano.

He started with an étude in 1826, creating an extended version in 1840 that was later refashioned in 1851 as the fourth of his Études d’exécution transcendante. When he created the symphonic poem in 1854, he reworked the coda so it wouldn’t have such an abrupt ending. He wanted to show Mazeppa who ‘falls as if dead, but rises to become a great leader of men.’ The new conclusion takes music from Liszt’s earlier March Héroïque to bring the story to an uplifting finale.

German conductor Oskar Fried leads the Berlin Philharmonic in this recording made in Berlin in 1928. Fried (1871-1941) was a noted conductor of Mahler’s works. He met Mahler in 1905 in Vienna and shortly thereafter, led the second complete performance of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony in Berlin. In 1920, he led a (nearly) complete Mahler cycle in Vienna, missing only Symphony No. 8, which he apparently never conducted.

Performed by

Performed by

Oskar Fried

Orchestra of the Royal Philharmonic Society

Recorded in 1928

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter