I have recently been listening to a lot of Frédéric Chopin’s music, and I am constantly in awe of the unbelievable and imaginative sound world he was able to create. It is a world of incredible passion and of poetry, a world that seemingly communicates the essence of human experiences and emotions. If you have ever taken serious piano lessons, you must surely remember countless hours of practicing scales and exercises to train and refine specific aspects of piano technique. Many composers of name and rank have written études to aid in this quest, but once we get to Chopin it all changes. He turned mundane and boring finger exercises into a veritable art form. Chopin composed three sets of études between 1829 and 1839, and they “not only represent a developing style of playing that reflects the new aspects of the piano, but also provide an encapsulation of Chopin’s unique style.”

Chopin playing the piano

They are still assigned to piano students all over the world because they are “carefully constructed pedagogical pieces with a specific technical aim.” However, they have also made it onto the concert stage because they are beautiful. When we have a closer look at the Chopin Études we quickly notice that a good many of them carry fanciful nicknames. It might surprise you that Chopin named very few of his own compositions, almost always preferring to refer to them by opus and by number. As such, the nicknames come from a variety of sources, including enthusiasts, critics, performers, or fans. Whatever their origins, these nicknames attempt to describe a particular technical aspect or peer beyond the notes to discover some thinly veiled emotions. In this little exploration of nicknamed compositions by Frédéric Chopin, let’s get started with the “Waterfall.”

Frédéric Chopin: Étude in C major, Op. 10, No. 1 “Waterfall”

Nobody really knows where the “Waterfall” nickname originated, and the legendary Vladimir Horowitz refused to perform this étude in public. He explained, “For me, the most difficult one of all the études is the C Major, the first one, Op. 10, No. 1.” Friederike Müller-Streicher, a student of Chopin relates that her teacher told her, “You shall benefit from this Etude. If you learn it according to my instructions, it will expand your hand and enable you to perform arpeggios like strokes of the violin bow. Unfortunately, instead of teaching, it frequently un-teaches everything.”

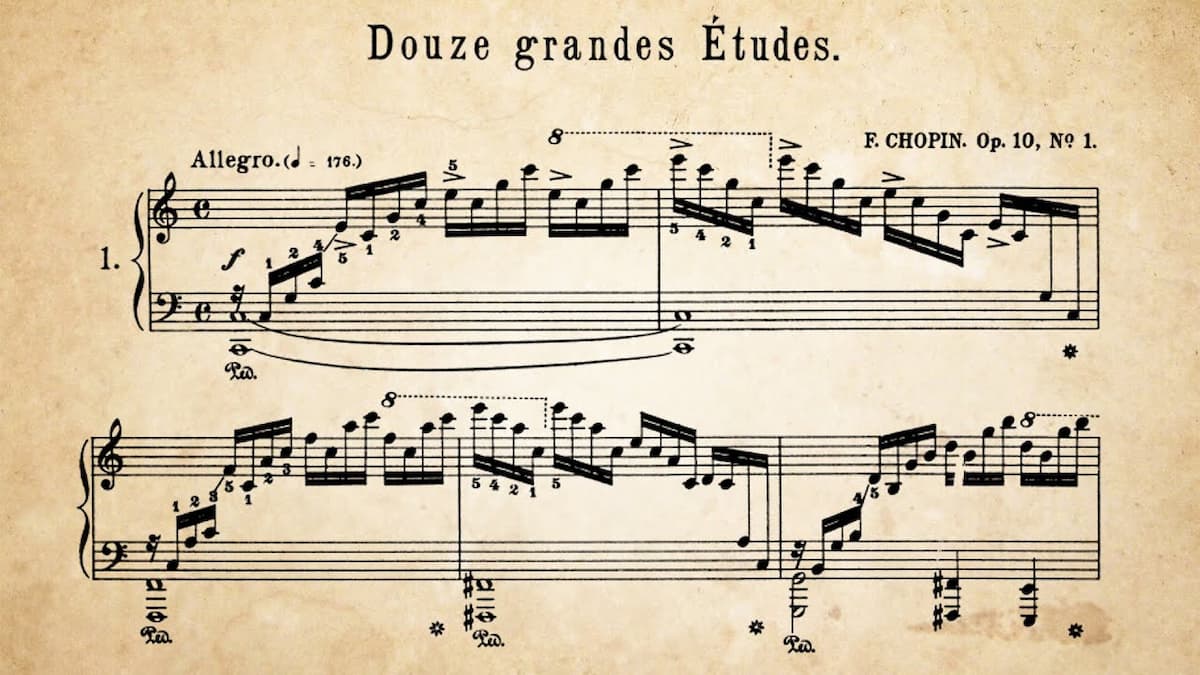

Opening of Etude Op. 10 No. 1 “Waterfall”

The piece focuses on a rippling chord progression based on chords of a tenth and covering up to six octaves. Supported by slow legato octaves in the left hand, the right-hand cascades up and down the keyboard. It almost becomes hypnotic, and the “Waterfall” nickname seems to fit the character of the piece really well.

Frédéric Chopin: Étude in E major, Op. 10, No. 3 “Tristesse”

The étude in E major, Op. 10, No. 3 is often likened to a nocturne. “It is a piece of intimate character and rich cantabile melodies, relieved in its middle section by a highly effective and novel character.” Early commentators considered it among Chopin’s loveliest compositions as it “combines classical chasteness of contour with the fragrance of romanticism.” This study carries the “Tristesse” (Sadness) or sometimes “L’Adieu” (Farewell) nicknames. These names were not supplied by Chopin but are based on an anecdotal description by the Chopin biographer Frederick Niecks. Apparently, Chopin said to his German pupil and copyist Adolph Gutmann that he “had never in his life written another such beautiful melody.” And when Gutmann was studying this piece “Chopin lifted his arms with his hands clasped, suddenly began weeping and cried, O, my fatherland!” If we hear this étude within this context, it is easy to discover sadness and an expression of nationalism. Despite its undoubtedly highly emotional appeal, however, many critics and performers consider the nicknames poorly chosen. They suggest that it should probably be heard as an expression of nostalgia for his homeland, and it is undoubtedly one of Chopin’s most popular and best-loved compositions.

Frédéric Chopin: Étude in G-flat major, Op. 10, No. 5 “Black Keys”

While the so-called “Black Key Étude” is one of the composer’s most popular pieces, the composer did not believe it to be his most interesting one. In a letter to his pianist friend Julian Fontata from 25 April 1839, he commented on a performance of this étude by Clara Wieck. “Did Wieck play my Étude well? How could she have chosen precisely this étude, the least interesting for those who do not know that it is intended for the black keys, instead of something better! It would have been better to remain silent.” It is easy to see how this particular étude gets its nickname, as the quick accompaniment in the right hand is primarily played on the black keys of the piano. In his article on piano etudes for the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in 1836, Robert Schumann classified this study under the category “speed and lightness.” His compatriot Theodor Kullak heard a piece “full of Polish elegance,” and the Chopin scholar Robert Collet believes that it “needs to be played with real gaiety and wit, though not without tenderness.” Since all keys matter, there is one white key used in the right hand, can you find it?

Frédéric Chopin: Étude in C minor, Op. 10, No. 12 “Revolutionary”

The concluding étude of the Op. 10 set is the so-called “Revolutionary Étude,” or alternately “étude on the Bombardment of Warsaw.“ That particular nickname is not by Chopin, but its associated sentiment makes it one of the composer’s most famous works. It was composed in the autumn of 1831 during Chopin’s first year in Paris.

Russian attack on Warsaw, 1831

Away from his home and his friends and family, Chopin was worried about the ongoing political turmoil in Poland. It all came to a head in the failed November Uprising of 1831, when Russian forces crushed the Polish mutineers. Chopin questioned the existence of God, “and if he did exist, how could He not avenge the Russian crimes against Poland.” Supposedly he cried out, “All this has caused me much pain. Who could have foreseen it?” Whether it was intended or not, it is easy to hear Chopin’s frustration and anger in this work. Just listen to the opening dramatic chord and the downward spiraling lines. The left hand certainly never stops moving, and this study has been described as a “stormy and conflicted work, with a seemingly never-ending outpouring of emotion.”

Frédéric Chopin: Étude in A-flat major, Op. 25, No. 1 “Aeolian Harp”

While the set of Études Op. 10 is dedicated to “his friend Franz Liszt,” the second set of Études published only four years later as his Op. 25, is dedicated to Liszt’s mistress, Marie d’Agoult. The first study in Op. 25 is aptly nicknamed “Aeolian Harp.” Robert Schumann already praised this work and called it “a poem rather than a study.” In fact, the nickname “Aeolian Harp” was actually coined by Schumann, who believed the piece to sound similar to this mythical stringed instrument played by the wind. The alternate nickname “The Shepherd Boy” is based on a supposed anecdote related by the Polish pianist Jan Kleczyński. Apparently, Chopin advised a student to “picture a shepherd boy playing the melody on a flute while taking refuge in a grotto to avoid a storm. Personally, I like the “Aeolian Harp” image better as the melody notes in the right hand give the impression of being plucked, while the rustling accompaniment evokes the image of a harp being strummed.

Frédéric Chopin: Étude in F minor, Op. 25, No. 2 “The Bees”

Nobody knows who first appended the nickname “The Bees” to the Étude in F minor, Op. 25, No. 2. To be sure, it derives its nickname from the perpetual motion melody, “which buzzes with gentle chromaticism and meanders like a bee from flower to flower.” When I listen to this piece, I keep wondering if the commentators could not have come up with a better nickname. The primary interest is not really in the buzzing melody, but it is found in the tricky polyrhythm. The right hand in eighth-note triplets naturally has its accents on every third or every sixth note, while the left hand plays in quarter-note triplets against it. It’s comparatively simple to perfect the right and left hand alone but putting them together is the real challenge. Nickname aside, this étude prominently features in an anecdote involving Alexander Dreyschock and Franz Liszt. Apparently, Dreyschock tried to impress Liszt by playing the left hand of the Revolutionary Etude in octaves. It is reported that Liszt responded by playing the right hand of “The Bees” in octaves at full speed. Poor Dreyschock was left speechless.

Frédéric Chopin: Étude in E minor, Op. 25, No. 5 “Wrong Note”

The fifth étude in the Op. 25 set is nicknamed “Wrong Note,” as it abounds with minor seconds. Since Chopin hated it when people gave nicknames to his pieces, the moniker “Wrong Notes” almost certainly did not originate with the composer.

Opening of Etude Op. 25 No. 5 “Wrong Note”

In fact, there is nothing “wrong” with this étude at all, as the nickname simply describes grace-note chords in a series of resolving dissonances.

Frédéric Chopin: Étude in A minor, Op. 25, No. 11 “Winter Wind”

Chopin refused programmatic intent for his music, but since his music is very evocative of images and emotions, many of his compositions have attracted nicknames or titles. Étude Op. 25, No. 11 in A minor, is often referred to as the “Winter Wind.” Considered one of the most difficult études in Chopin’s arsenal, the opening four bars referencing the main melody were added just before publication. This calm before the storm is followed by a study requiring stamina, dexterity, and technique. With the right hand providing cascading passagework that requires the passing of the thumb under the 5th finger, the left-hand plays the stern chords of the “Winter Wind.”

Frédéric Chopin: Étude in C minor, Op. 25, No. 12 “Ocean”

It is not difficult to hear why the Étude No. 12 in C minor carries the nickname “Ocean.” This study is a passionate journey up and down the keyboard for both hands. The chordal pattern of the opening seems relatively simple, but things get complicated in the tension-filled middle section. In fact, there seems to be some controversy on how these lush chromatic chords are to be voiced and performed, and which notes are to be emphasized. Either way, this study places tremendous technical demands and exceptional interpretative considerations on the performer. While the nickname “Ocean” seems well chosen, the emotional qualities have frequently been described as “mournful, yearning, sublime, and sentimental.”

Frédéric Chopin: Prelude in D-flat major, Op. 28, No. 15 “Raindrop”

Nicknames aren’t confined to Chopin’s Études; we also find them in his 24 Preludes. Maybe the most famous is Op. 28, No. 15 nicknamed “Raindrop.” A delightful anecdote relates that ” target=”_blank”>George Sand and her son Maurice returned one evening to Mallorca in 1838. They found a highly emotional Chopin exclaiming, “Ah, I knew well that you were dead because while I was playing the piano, I had a dream.” According to Sand, “Chopin saw himself drowned in a lake. Heavy drops of icy water fell in a regular rhythm on his breast, and when I made him listen to the sound of the drops of water indeed falling in rhythm on the roof, he denied having heard it. He was even angry that I should interpret this in terms of imitative sounds. He protested with all his might—and he was right to—against the childishness of such aural imitations. His genius was filled with the mysterious sounds of nature, but transformed into sublime equivalents in musical thought, and not through slavish imitation of the actual external sounds.” We really don’t know which prelude Chopin played for Sand, but the repeating A-flat does suggest the gentle patter of rain to lots of listeners.

Frédéric Chopin: Waltz Op. 64, No. 1 “Minute”

The Danish-American pianist and comedian Victor Borge performed one of my favorite classical-music comedy sketches. Borge wondered how the Chopin Waltz in D-flat major, Op 64, No. 1 got its nickname “Minute Waltz.” The comedian’s answer is very simple, as he tells the fictional story that Chopin loved perfectly soft-boiled eggs. Since his housekeeper could never get the timing correct, he composed the “Minute Waltz.” Once he had played the waltz three times, the egg would be perfect. It’s certainly a fun and highly unlikely story as performances of that particular waltz will typically be closer to two minutes. And while the nickname “Minute Waltz” is primarily known throughout English-speaking regions, the piece is sometimes referred to as “Valse du petit chien” or waltz of the puppy. According to a Chopin biographer, this waltz got its name from Chopin watching a small dog chasing its tail. Whatever the actual origin of this nickname, this waltz is undoubtedly one of the most famous and best-loved Chopin compositions.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Dear Hermione Lai. As we share a passion for Chopin’s music and since reading your feature on his Grandes Etudes – I wonder if you would be interested to receive a copy of my book, ‘Chopin – Interpreting the Grandes Etudes’, which includes two CDs. The 2nd CD is presented as an illustrated commentary on each etude with comparative interpretations and variants, based on my intensive research into all original sources over many decades. The 1st CD is a performance of the opp. 10 and 25 complete. // Throughout my career as an international pianist, I have recorded over 15 cds of Chopin. Currently my 6-cd series is available via my website, along with information and one of my articles on Chopin interpretation. I would be really pleased to hear from you if you require more details. With best wishes. Angela Lear http://www.angelalear.com

Dear Angela, thank you so very much for your kind comment. There is still so much I want and have to learn about Chopin and his wonderful music. I will look at your website immediately. Could you possibly send a soft copy of your book to [email protected]? I would love to read about your research and your interpretations.

All the best,

Hermione

The above letter is addressed to Hermione Lai, following her excellent feature on Chopin’s Etudes. Thank you.

Thank you so much for this thorough and enlightened article on Chopin’s music.

However,I have been wondering about the nickname ” winter waltz” mentioned several times on Youtube for Chopin’s waltz in C sharp minor opus 64 no2, and have not been able yet to pinpoint any clue or explanation for it.

What about it?can you give me some clues about the origin and / or legitimacy of the nickname .

Best regards

Armelle

Hi Armelle, in all my readings I’ve never come across the name “Winter Waltz.” Is it possible that youtubers confuse it with the “Winter Etude”? I’ll keep looking….”

Best

Hermione