Nicolas-Charles Bochsa, 1842

He was a forger, bigamist, and womanizer whom Fétis called “as distinguished an artist as he was a miserable man.” His name was Nicolas-Charles Bochsa (1789-1856), and we must count him among the greatest harpists of the 19th century. Born in Montmédy, not far from the Belgian border, young Nicholas was a prodigious musical talent. He composed a flute concerto at the age of eleven, and an oratorio at sixteen. At the same age he also wrote the opera Trajan, which was produced in honor of Napoleon’s visit to Lyons. Once the family moved to Paris—after a short time in Bordeaux—he entered the Paris Conservatoire in 1806. He finally decided to make the harp his principal instrument, although throughout his life he was a skillful player of almost every known instrument. Intensely curious, he constantly expanded the technical and expressive range of the instrument and discovered new effects. While his music is not really profound, it is rather adventurous and occasionally brilliant.

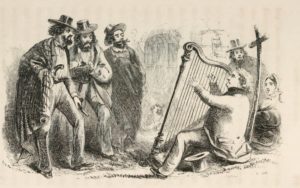

Bochsa playing for Mexican Bandits

Bochsa became incredibly popular in France and abroad, and by 1813 he was named harpist to the emperor Napoleon. Before receiving his appointment with Louis XVIII in 1816, he composed seven operas for the Opéra-Comique, and a 15-movement requiem for the beheaded remains of Louis XVI. At the height of his popularity and musical career, Bochsa surprisingly turned to a life of crime. He developed a rather lucrative business in forged documents of various kinds, including faking signatures ranging from the Duke of Wellington to his own compositions professor Étienne Méhul. Once he was found out, Bochsa quickly fled to England to escape prosecution. On 17 February 1818 the Paris Court of Assize condemned him, in his absence, to 12 years imprisonment with a fine of 4000 francs, and to be “branded with the letters ‘T.F.’ (‘travaux forcés’, or forced labour – the standard penalty for forgers).” However, things initially went well for Bochsa in England. He soon had more students than he could accommodate, and he was in constant demand as a harpist and conductor. In 1822 he was appointed professor of harp at the newly formed Royal Academy of Music, and he was named general secretary and director of the Lenten Oratorios.

Charles Nicholas Bochsa: Harp Concerto in C Major (Olga Erdeli, harp; Victor Kornachev Chamber Orchestra; Victor Kornachev, cond.)

Anna Bishop, 1856

Not all went smoothly in England for Bochsa, however. News of his forgery conviction had reached the Isles, and it was suggested that he had a wife in France despite the fact that he had married Amy Wilson in England. There was also a rumor that Bochsa had gotten sexually involved with a nun! In addition, he declared bankruptcy on 4 May 1824 and lost his position at the RAM in 1827. He did retain his conducting appointment at the King’s Theatre and gave annual concerts, which were exceedingly popular. He also composed three ballets and got in serious trouble for reducing the salaries of the orchestral players. When the principal players resigned, he simply replaced them with inferior and cheaper musicians. Bochsa toured the British Isles throughout the 1830’s to extreme popular success, and he teamed up with the composer Sir Henry Bishop and his wife Anna. Anna Bishop was known for her lovely high soprano voice, and in 1839 Bochsa and Anna eloped.

Charles Nicholas Bochsa: Grand Sonata, Op. 52 (Olivier Dartevelle, clarinet; Rachel Talitman, harp)

Sheet music of Bochsa’s ‘Je Suis La Bayadere’

They stopped in Naples for two years, and first appeared in New York in 1847. American moral outrage aside, the couple achieved resounding success on Broadway and a grand tour took them to New Orleans in the south, Quebec in the north, and major cities in between. They even toured Mexico from June 1849 to May 1850, and California in 1854 and 1855. Having to avoid France and England, the couple arrived in Sydney, Australia, in December 1855. Bochsa became ill, and they gave one last concert together. It has been suggested that Bochsa wrote a requiem for himself while on his deathbed, but a contemporary source states “he merely wrote down a mournful refrain on a scrap of paper, which was used as the basis for a requiem at his funeral.” Anna Bishop was heartbroken and commissioned an elaborate tomb for him in Camperdown Cemetery. She subsequently returned to New York, and having finally been granted a divorce from Sir Henry, returned to London to marry Martin Schultz on 20 December 1858. A biographer compared the harpist’s criminal tendencies to “Gesualdo’s crime, Wagner’s lifestyle, and Beethoven’s personality” and suggests “that the judgment against their deed should not influence the evaluation of the quality of their talent.” I let you be the judge of that.

Charles Nicholas Bochsa: Nocturne Op. 51, No. 1 (Pierre Henri Xuereb, viola; Rachel Talitman, harp)