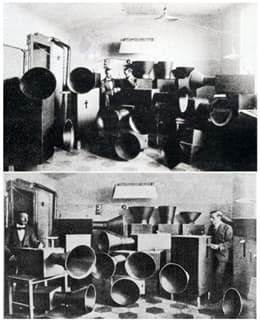

Luigi Russolo and Ugo Piatti with noise machines, Milan, 1913

The percussion ensemble is a relatively new performance genre among all classical music ensembles. Even though percussion instruments were used in orchestral works as early as in the Baroque era, music written only for percussion instruments did not come into play until the 1930s. At the turn of the 20th century, more prominent percussion elements were found in some significant compositions, such as Igor Stravinsky’s Petrushka (1911) and The Rite of Spring (1913). His L’Histoire du Soldat (1918) is widely known as one of the earliest examples of a multi-percussion set up for a single percussionist. The rise of popular music and dance in the 1900s and the futurist movement further opened the door to percussion music.

L’Arte dei Rumori (The Art of Noises)

The futurist movement, founded by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909, was supported by groups of artists who pursued everything modern at the time. One notable example is Luigi Russolo’s futurist manifesto, the L’Arte dei Rumori (The Art of Noise) in 1913, which proposed the expansion of sonic experiences, such as noise, in music compositions. Russolo created a set of 27 intonarumori instruments that imitate different types of “noise.” As such, machine music became one of the compositional styles in the 1920s. George Antheil’s Ballet Mécanique is the most prominent representative of this genre.

Amadeo Roldán

After such a long introduction to percussion music, when did the earliest percussion ensemble music appear? One of the earliest examples of percussion ensembles was Rítmicas No. 5 and No. 6 (1930) by the celebrated Cuban composer Amadeo Roldán Gardes (1900-1939). Rítmicas No. 5 is based on the Cuban son, which was originated as a rural song and dance in a duple meter at a moderate to fast tempo. It is scored for nine performers; except for the timpani, all the instruments are traditional Cuban instruments, such as clave, bongo, quijada, and marimbula. Rítmicas No. 6 includes similar instruments as in No. 5, but it features another popular Cuban genre, rumba.

Amadeo Roldán: “Ritmica No. 5”

Amadeo Roldán: “Ritmica No. 6”

In addition to Amadeo Roldán Gardes, there were other influential Latin American composers who pioneered the development of the percussion ensemble repertoire. These composers include Cuban José Ardévol and Mexican composer Carlos Chávez, who wrote significant works for percussion ensemble during the 1930s-1940s.

José Ardévol

José Ardévol (1911-1981) was born in Spain and moved to Cuba in 1930. His Estudio en forma de preludio y fuga (1933) was his earliest composition for percussion ensemble and the largest ensemble for percussion in the 1930s. It is scored for 31 performers to play over 35 instruments. Percussion instruments include Afro-Cuban instruments (claves, güiros, maracas, bongos, cowbells, and African drums), orchestral instruments (cymbals, triangle, gong, tam-tam, small military drum, snare drums, timpani, and bass drums). It also includes police whistles, sirens, whips, anvils, and handclaps to produce the sound effect throughout the piece.

José Ardévol: Estudio en forma de preludio y fuga

Carlos Chávez

Mexican composer Carlos Chávez (1899-1978) was one of the most influential composers of the 20th century. Besides his second symphony, Sinfonía India, his Toccata for percussion instruments (1942) remained one of his most famous works. It is a three-movement work scored for sextet. Latin American instruments, such as Indian drums, claves, maraca, are used in the piece, along with standard percussion instruments like glockenspiel, xylophone, chimes, gongs, etc.

Carlos Chávez: Toccata for percussion instruments

Henry Cowell playing the shakuhachi with Edgar Varèse © The Cowell Estate

Both Roldán’s and Chavez’s use of Latin American music styles influenced many of their contemporaries, such as Edgard Varèse (1883-1965), and Henry Cowell (1897-1965). Edgard Varèse’s Ionisation was written one year after Rítmicas. Roldán and Varèse had a good friendship; Roldán not only sent some Cuban percussion instruments to Varèse but also gave him advice on the instrumentation of Ionisation.

Ionisation features the expansion and variation of rhythmic cells to symbolize the ionization of molecules. The score calls for 13 players, and the instruments include anvils, bass drum, castanets, a large Chinese cymbal, Chinese blocks, cowbell, cymbals, guiro, gong, whip, and more.

Edgard Varèse: Ionisation

Henry Cowell’s famous percussion ensemble piece, Ostinato Pianissimo (1934), was written after visiting Cuba in 1929. Cowell was familiar with Roldán, who later gave him advice on instrumentation in Ostinato Pianissimo. The piece calls for eight percussionists and incorporates the Cuban guiro and bongos with other percussion instruments like woodblocks, tambourine, and xylophone. It also requires string piano, an extended technique that requires playing directly on the strings.

Henry Cowell: Ostinato Pianissimo

When Varèse’s Ionisation was premiered at a Pan American Association concert on March 6th, 1933, William Russell’s Fugue for Eight Percussion Instruments, also made its premier. William Russell (1905-1992) was a leading American composer of percussion pieces, and he was particularly famous for incorporating African, Caribbean, and Asian instruments into his works. In the Fugue, a rhythmic subject is first introduced by a muted snare drum marked “Handkerchief over drum head.” This rhythmic subject is played by other percussion instruments one after the other.

William Russell: Fugue for Eight Percussion Instruments

In 1939, William Russell composed Percussion Studies in Cuban Rhythms. The music uses Cuban instruments to portray the Cuban sound and style, including bongos, cowbells, güiro, maracas, claves, quijada (jawbone), and marímbula. It was premiered in 1939 with John Cage conducting.

William Russell: Three Cuban pieces

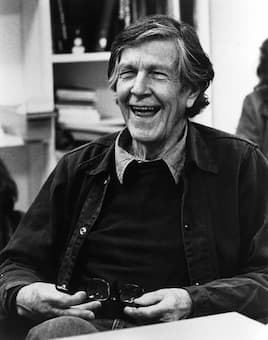

John Cage

The experimentalist composer John Cage (1912-1992) composed many significant percussion works throughout his career. Living Room Music (1940) is my favorite among his earliest compositions written for percussion. Dedicated to then-wife Xenia Andreyevna Kashevaroff, Living Room Music is a percussion quartet with four movements. The first and the last movements, titled To Begin and End, are particularly written for percussion “instruments,” but Cage did not specify any percussion instruments. Instead, he instructed performers to use any household objects as instruments, such as magazines, cardboard, and floor. The second movement is a speech quartet, and the text is adapted from The World is Round by Gertrude Stein. The third movement is an optional movement with a given melody played by one of the performers on “any suitable instrument.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

John Cage: Living Room Music