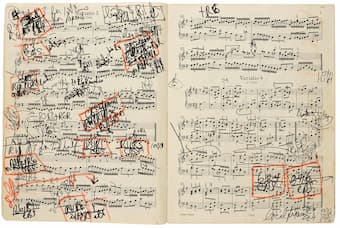

Glenn Gould’s annotations on Bach’s Goldberg Variations

The musical score is both a text and a visual artefact that can be converted by the musician into an aural experience, for player and audience. In order to achieve this, virtually every score is annotated by those musicians who worked on it, and the notion of a pristine, clean score seems alien to most of us. From an interpretative point of view, the score is not just a set of instructions from the composer but the starting point for a musical journey of exploration, allowing personal interpretation and meaning. Annotations assist in this journey, from fingering schemes to articulation, dynamics and expressive markings to more personal signs and symbols that enable us to navigate and interpret the musical text (for example, I favour “TYT”, borrowed from one of my teachers, which means “Take Your Time” in passages where I tend to hurry, or a series of dots to indicate rubato).

Coming back to a previously annotated score after an absence from it can be an interesting experience. Just as one’s musical development does not stand still, nor reach a point of “finishedness”, as it were, so one’s annotations may also change over time. Previous annotations offer a snapshot of where one was, technically, interpretatively and artistically, with the music at that time, while teachers’ annotations mark the point where one was in one’s study.

Often existing annotations can be helpful (fingering schemes being the most obvious), but sometimes they are a distraction – as I found when I revisited Liszt’s three Petrarch Sonnets for a recent masterclass. My original annotations were over 10 years old, from the time when I was working towards a professional performance diploma, and they reveal my insecurities about my technical and artistic abilities with regard to this music. Looking back through the score, it was quite evident to me that, at that time, I relied heavily not only on clear directions about “how to play” this music, but also nudges and hints to ensure details were not overlooked, plus some rather colourful descriptions to bring out certain effects -“dirty pedalling”, for example, to create a specific wash of sound in one passage.

For me, these old annotations were now a major distraction and I erased most but the essential markings, to enable me to start afresh with the music.

Franz Liszt: Années de pèlerinage, 2nd year, Italy, S161/R10b – No. 6. Sonetto 123 del Petrarca (Sonnet 123 of Petrarch) (Francesco Piemontesi, piano)

However, in the case of Schubert’s penultimate piano sonata, the D959 in A Major, a piece with which I spent some four years of study in preparation for my final performance diploma, I kept my original working copy of the score, by this time very dog-eared and heavily annotated, as a document to refer back to, while buying a replacement copy (same edition) for daily practice, plus an additional copy in which my teacher could write his notes. I’ve still got all these copies of the score and they now represent almost “historical documents” for me – a reminder of a time when I worked almost exclusively on that sonata.

An encounter with an adult amateur player, who came to me recently for a one-off lesson on Mozart’s Rondo in A minor, K511 (a work which I adore), made me realise how personal our annotations can be. Aware that the other person was eagerly trying to see my annotations on the score – and copy them into her own edition! – I hastily shut the music and returned it to my bookshelf. It was clear that the student thought that my annotations could give her some special insights into the music, or the key to how to play it (in both instances, a fallacy!), and I really didn’t want my markings to be used in this way; they were the result of my own research into the music and represented my own personal interpretative thoughts about it.

Looking at images of Glenn Gould’s annotations on his score of the Goldberg Variations, one wonders how he managed to navigate the music, the notes almost entirely obscured by his own markings. One can only assume that at some point he had the music sufficiently memorised, and the annotations become, in his mind, absolutely integral to the printed score. I suspect we all have annotations like this on our scores – those markings that we simply cannot bear to erase and which become so familiar to us, visually.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Rondo in A Minor, K. 511 (Jeremy Denk, piano)