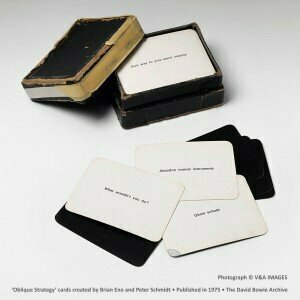

Oblique Strategies (subtitled Over One Hundred Worthwhile Dilemmas) is a deck of 7 by 9 centimetres (2.8 in × 3.5 in) printed cards in a black container box, created by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt and first published in 1975. Each card offers an aphorism intended to help artists (particularly musicians) break creative blocks by encouraging lateral thinking. (Source: Wikipedia)

Oblique Strategies (subtitled Over One Hundred Worthwhile Dilemmas) is a deck of 7 by 9 centimetres (2.8 in × 3.5 in) printed cards in a black container box, created by Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt and first published in 1975. Each card offers an aphorism intended to help artists (particularly musicians) break creative blocks by encouraging lateral thinking. (Source: Wikipedia)

The Oblique Strategies cards were most famously employed by Brian Eno during the recording of David Bowie’s Berlin triptych Low, “Heroes” and Lodger in the 1970s. These brief gnomic aphorisms, selected randomly, can bring new or unexpected ways of thinking to seemingly intractable problems and difficulties, not just those encountered during creative processes such as writing, composing or painting/making art, but also in everyday life. Oblique Strategies Cards can also be used in music practice to help enliven practising or shine a new light on an issue which may have been causing one problems, or just to help one think and act more creatively and spontaneously during practice.

I have taken just a few Oblique Strategies and considered how they might be used in day-to-day practising, and also in preparation for performance. These are my own responses to the cards, and are simply suggestions and perhaps an inspiration to others to try this approach.

‘Repetition is a form of change’

So, we all know that repetitive practise is the activity which fixes music in head, hands, eyes and ears. Repetition is what trains the muscular memory (what psychologists call “procedural memory”, since in reality our muscles do not retain a memory of movement). But practising the same phrase or section over and over again, 20, 50, perhaps 100 times, can be dull and unsatisfying. So make each repetition count: listen, look, think, consider, so that each subsequent repetition has value.

‘What mistakes did you make last time?’

An obvious and useful aphorism. Never ignore mistakes: consider why they happened and how they can be resolved. See them in a positive light – we can always learn from mistakes – and take action to ensure they do not reoccur.

‘Look at the order in which you do things’

An excellent suggestion! If your practise sessions always follow the same pattern – warming up with scales and exercises, perhaps, before moving on to work on pieces – try mixing things up a bit. Maybe do some warm up exercises away from the piano while thinking about what you need to work on, and then try a quick study or some sight-reading?

‘Listen to the quiet voice’

Taking time to listen carefully and play quietly (and slowly) is an important element of practise and one that is too often overlooked by youngsters (and more senior players too) who may want to play with all the exuberance of youth, or who simply want to get through their practise session as quickly as possible. When we play quietly and slowly we allow ourselves more time to consider the music: look at the details, the different “voices” and lines of melody. Maybe a “quiet voice” in the left hand has not been given enough attention? Try highlighting it and see what effect it has.

‘You don’t have to be ashamed of using your own ideas’

Don’t always rely on a teacher to guide you in aspects of technique, interpretation and musicality. Trust your instincts and be brave, learn from listening and observing others, in concert and on recordings. Make your own judgements. A good teacher will guide and advise and offer suggestions if something you are doing is “tasteless” or not in keeping with the genre or character of the music.

‘Use “unqualified” people’

This ties in with the previous card. Asking non-specialists and those who have little knowledge of music to listen to your playing can be a useful and enjoyable exercise. Take their comments on board. As musicians it is not healthy to exist in an isolated ivory tower.

‘Turn it upside down’

My father used to do this when he was practising. He was a fine amateur clarinettist. Turning the music upside down was a common practice in orchestral rehearsals to break the monotony and add a new slant on familiar music. It’s not as straightforward for a pianist, but it’s a fun exercise. Or try practising everything with each hand, and things in symmetrical inversion, or transpose (keeps the brain alert!).

“Are there sections? Consider transitions”

Music is constructed from clear ‘architecture’, and usually in defined sections. We tend, by necessity to learn section by section and this can lead to a piece sounding disjointed, despite our best efforts to create a sense of flow throughout the entire work. So, take time to consider the bridges and transitions between sections: practise the endings and beginnings of sections and think about how the different sections relate to one another, or offer contrasts.

‘Use fewer notes’

Not to be taken literally for we should always show fidelity to the score, but sometimes our playing can genuinely appear too “notey”. Try different forms of touch and attack, consider the sounds, phrasing, and dynamic range.

‘Make a sudden, destructive, unpredictable action; incorporate’

If you’re someone who enjoys improvisation, this will strike a chord (forgive the pun!). And even if you’re not a natural improviser, why not try incorporating some improvisation into your regime? And even within the rather stricter confines of serious practising, one should allow the unexpected and see where it leads…..

‘Convert a melodic element into a rhythmic element’

Another improvisatory impulse which can be incorporated into everyday practise. And maybe that melody could do with more rhythmic vitality to bring additional colour to it?

‘Define an area as “safe” and use it as an anchor’

Here’s one to help with performance anxiety. Think about the last time you played that piece or pieces and recall the positive feelings associated with it. Try and recreate those feelings in your mind, and body, as you prepare for the next performance. Instead of focusing on the “what if’s?” or allowing negative thoughts to creep in, anchor your attention onto positives drawn from previous successful performances.

And a few more of my favourites, for no particular reason:

‘Change nothing and continue with immaculate consistency’

‘Make an exhaustive list of everything you might do and do the last thing on the list’

‘Imagine the music as a moving chain or caterpillar’

‘What would your closest friend do?’

There are a number of random Oblique Strategies generators online, smart phone apps, and even a few Twitter accounts, or of course you could purchase the cards in their traditional format. Thank you for reading: I’m off to ‘do the washing up’.

Listen to ‘Heroes’ by David Bowie

More Opinion

-

The Predictability of the 2025 Van Cliburn Competition Was Hong Kong's Aristo Sham the 'predictable winner'?

The Predictability of the 2025 Van Cliburn Competition Was Hong Kong's Aristo Sham the 'predictable winner'? -

The Unpredictability of the 2025 Queen Elizabeth Competition Discover why these results have sparked debate among classical music fans

The Unpredictability of the 2025 Queen Elizabeth Competition Discover why these results have sparked debate among classical music fans -

What Makes a Good Concert? A memorable concert requires four essential elements. Find out here

What Makes a Good Concert? A memorable concert requires four essential elements. Find out here -

The Musician’s ‘Non-Negotiables’ Want to level up your music practice? Take inspiration from 'The Bear'

The Musician’s ‘Non-Negotiables’ Want to level up your music practice? Take inspiration from 'The Bear'