Sergei Prokofiev would make a compelling case study for a textbook investigating the psychology of the exceptional child. Supremely talented in musical matters, Sergei had composed a number of overtures, various piano pieces and his first opera The Giant by age 9! Eagerly supported by a highly educated and ambitious mother, Sergei keenly knew that he was special. His confidence in musical matters, however, was contrasted by some rather awkward behavior within his social surroundings. Several years younger than most of his classmates at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, he was viewed as eccentric and arrogant, and he delighted in annoying his fellow students by keeping statistics on their errors and mistakes. Yet, sporting a full head of fiery-red hair and always dressed in his Sunday best, Prokofiev was rather popular with the fairer sex. His conservatory classmate Vera Alpers wrote in her diary in 1908, “Prokofiev was becoming very “in”… During a rehearsal he paid attention to my long fingers, took my hand, embarrassed me by saying it was beautiful… I wonder why I like him so much. He is a real egoist badmouthing everyone… And still…”

Sergei Prokofiev would make a compelling case study for a textbook investigating the psychology of the exceptional child. Supremely talented in musical matters, Sergei had composed a number of overtures, various piano pieces and his first opera The Giant by age 9! Eagerly supported by a highly educated and ambitious mother, Sergei keenly knew that he was special. His confidence in musical matters, however, was contrasted by some rather awkward behavior within his social surroundings. Several years younger than most of his classmates at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, he was viewed as eccentric and arrogant, and he delighted in annoying his fellow students by keeping statistics on their errors and mistakes. Yet, sporting a full head of fiery-red hair and always dressed in his Sunday best, Prokofiev was rather popular with the fairer sex. His conservatory classmate Vera Alpers wrote in her diary in 1908, “Prokofiev was becoming very “in”… During a rehearsal he paid attention to my long fingers, took my hand, embarrassed me by saying it was beautiful… I wonder why I like him so much. He is a real egoist badmouthing everyone… And still…”

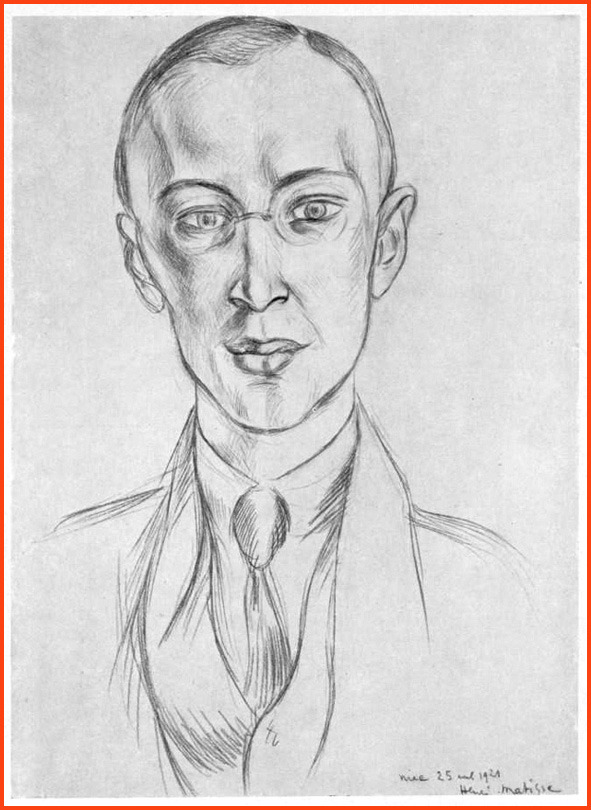

Sergei Prokofiev: “Eleonora,” 10 Pieces, Op. 12, No. 7 (version for harp)

Prokofiev’s first serious romance was clearly in the making when he called his fellow classmate Eleonora Damskaya “an ugly, miserable humpback.” In reality, she was stunningly beautiful, intelligent, an interesting conversationalist, and on her way to becoming a celebrated harpist. In fact, Eleonora would become famous throughout the Soviet Union performing under her married name, Eleonora Damskaya-Tontegoda. Prokofiev was completely infatuated, and he immortalized their relationship in music. His Prelude for Piano and Harp—also transcribed for solo harp—is one of the Ten Pieces for Piano, Op. 12, which is dedicated to Damskaya. Whenever Prokofiev was away from Petersburg, he sent postcards and flirtatious letters to Eleonora. “Mamselle Eleonora,” he writes from London on 25 June 1914, “I was very happy to receive your letter. True, I had to go get a magnifying glass, but that doesn’t matter. Though, in all honesty, you have miserable handwriting. Nevertheless, the contents were so interesting that they made up for ruining my eyesight…I’m waiting for your second letter.”

Their intimate and flirtatious correspondence continued even after Prokofiev was forced to depart from revolutionary Russia in 1918. Having decided to travel to America to stay for a while, Prokofiev traveled across Siberia to the Pacific. “My dear friend, what I’m seeing through the window has become more animated, and Baikal is just remarkably beautiful. My mood is excellent and we are circling around Khabarovsk on the new route to Vladivostok. Kharbin is impassable, so it’s impossible to get into China.” In the meantime, the revolutionary authorities raided Prokofiev’s old apartment. A public garage sale was quickly organized and Prokofiev’s personal belonging offered for sale. Eleonora borrowed money to buy the Schröder grand piano Prokofiev had been awarded upon his graduation from the St. Petersburg Conservatory. And thus, Prokofiev and his piano were reunited many years later. Prokofiev eagerly reported his impressions from America, while Eleonara was in the center of the action back home. Prokofiev had a frivolous attitude towards the Russian Revolution, and a number of letters to Damskaya from that time period have long been censored with the justification that “the portrait the letters paint of the composer was inappropriate for one of the leading figures of Soviet music, and would lead to awkward questions about his acceptance of Lenin, communism, and Soviet power.”

After a seriously long absence, Prokofiev was invited to play a number of concerts in Moscow and Leningrad in 1934. By this time he was married and father of two sons—more on that in our next episode—and Eleonora had long since married as well. However, an old proverb tells us that old flames burn hottest, and so it’s no wonder that the former lovers would meet again face to face. Nine months later, and not entirely unexpected, Eleonora gave birth to a son christened Alexander. Apparently, little Alexander looked like a carbon copy of his famous father, and Eleonora never made a secret as to the real identity of the boy’s actual father. Financially supported by his father, Alexander Tontegod became a research fellow at the local Institute of Physics and Technology in Leningrad. He was even awarded the State Prize of the Soviet Union for his research on solid-state matters. When Prokofiev died in March 1953, Eleonora donated over 200 of Prokofiev’s personal effects to the Moscow museum of music history.

You May Also Like

- Bigamist Prokofiev?

Sergei Prokofiev and Mira Mendelson Dictatorial societies are notorious for fostering environments of suspicion and fear. -

Sergei Prokofiev: Salvation for Modern Music? It is somewhat surprising that Prokofiev's earliest effort in the symphonic genre also became one of his most popular and most frequently programmed works.

Sergei Prokofiev: Salvation for Modern Music? It is somewhat surprising that Prokofiev's earliest effort in the symphonic genre also became one of his most popular and most frequently programmed works. - Lina and the Wolf

Sergei Prokofiev and Lina Codina The love story of Prokofiev and Spanish-born singer Lina Llubera -

Sergei Prokofiev: Enfant Terrible The piano was the prominent vehicle for Sergei Prokofiev’s musical expression.

Sergei Prokofiev: Enfant Terrible The piano was the prominent vehicle for Sergei Prokofiev’s musical expression.

More Love

- Untangling Hearts

Klaus Mäkelä and Yuja Wang What happens when two brilliant musicians fall in love - and then fall apart? -

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more

The Top Ten Loves of Franz Liszt’s Life Marie d'Agoult, Lola Montez, Marie Duplessis and more - Mathilde Schoenberg and Richard Gerstl

Muse and Femme Fatale Did the love affair between Richard Gerstl and Mathilde Schoenberg served as a catalyst for Schoenberg's atonality? - Louis Spohr and Marianne Pfeiffer

Magic for Violin and Piano How did pianist Marianne Pfeiffer inspire a series of chamber music?