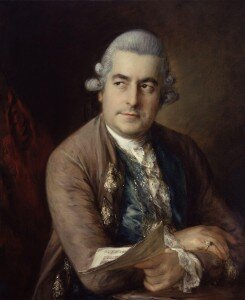

Gainsborough: Johann Christian Bach (1776)

(National Portrait Gallery, London)

In April 1782, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart famously wrote to his father, “I suppose that you have heard that the English Bach is dead? What a loss to the musical world!” Johann Christian Bach, known in London circles as John Bach, had found fame, success and financial stability in the British Isles. He rubbed shoulders with the royal family and gave music lessons to the queen and her children, organized chamber concerts at court, directed the queen’s band, and accompanied the flute-playing king. His operas were immediately successful and financially profitable and he lived comfortably in Soho and Mayfair, and later in Richmond and Paddington. John Bach cleverly took advantage of the flourishing music trade and published a whole series of works, including a number of highly influential keyboard concertos and sonatas.

Johann Christian Bach: Keyboard Concerto in F Major, Op. 13, No. 3 (Anthony Halstead, piano/cond.; Hanover Band)

Alexandre Auguste Robineau: Karl Friedrich Abel

In his day, John Bach was one of the leading composers and musicians in London, and he counted aristocrats, authors, poets, painters and musicians as his close personal friends. And that included Leopold, Nannerl, and Wolfie Mozart, who visited London in 1764. Wolfie was only eight years old and Georgian London presented him with a vibrant and exciting musical environment. John Bach took young Mozart under his wings and introduced him to musical styles and conventions from Germany, Italy, and England. In turn, Mozart retained his admiration, love and respect for John Bach throughout his life. A humorous anecdote relates that when Mozart borrowed, studied and copied the score to John Bach’s opera “Lucio Silla” from Georg Joseph Vogler, he was greeted by the following words a couple days later. “Vogler asked me with an obvious sneer: ‘Well, do you find it beautiful?… It has one fine aria…why of course, that hideous aria by Bach, that filthy stuff.” Mozart subsequently wrote to his father, “I thought I should have to seize his front hair and pull it hard, but I pretended not to hear him, said nothing, and walked away.”

Johann Christian Bach: Adriano in Siria (excerpts) (Anna Devin, soprano; Eleanor Dennis, soprano; The Mozartists)

Hanover Square

Johann Christian Bach was born on 5 September 1735, the eighteenth child of Johann Sebastian Bach. He showed great musical aptitude, and after the death of his father, he moved to Berlin and studied with his half-brother Carl Philipp Emanuel. However, he was not happy in Berlin and departed for Italy in 1755. His Italian operas soon attracted much attention, and the management of the King’s Theater in London contacted him. After some negotiations, Johann Christian was commissioned to compose two works for the 1762/3 Season. John Bach quickly joined the best European musicians working in London, all attracted by the emergence of a new merchant class and the promise of financial rewards. Bach became roommates with the composer and viola da gamba player Carl Friedrich Abel, who had studied with Johann Sebastian in Leipzig. They decided to collaborate in a series of concerts known as the Bach-Abel concerts.

Johann Christian Bach: Symphony in G minor, Op. 6, No. 6 (Hanover Band; Anthony Halstead, cond.)

John Nixon: Karl Friedrich Abel

The Bach-Abel concert series had a major impact on London concert life, and programs included “the latest symphonies, concertos, chamber and vocal works of Bach, Abel and other fashionable composers. The performers were the best in London, and often of German origin; they included the oboist J.C. Fischer, the violinist Wilhelm Cramer (father of John, the pianist) and later the pianist J.S. Schroeter, one of Bach’s pupils.” The Bach-Abel concerts, the first subscription concerts in England, reached a great level of popularity, and in 1774 they acquired a property in Hanover Square. In partnership with Sir John Gallini they build a new concert hall, the Hannover Square Rooms or the Queens Concert Rooms. Primarily slated for musical performances, the lavishly appointed building was adorned with paintings by Thomas Gainsborough. “This was the final home of the Bach-Abel concerts, but it also marked the beginning of their decline as Bach’s finances were depleted and receipts diminished.”

Johann Christian Bach: Quintet in D Major, Op. 22, No. 1 (English Concert; Trevor Pinnock, harpsichord)

It has been reported that either a servant or a minor business partner defrauded John Bach of more than £1000. In the event, his bank account became overdrawn and the Bach-Abel concerts continued to lose money. Bach’s health also continued to decline and his wife, the singer Cecilia Grassis reported, “he suffered from a long illness which led him to the tomb.” On 14 December 1781 the singer Angelo Morigi sent news to Padre Martini that Bach was suffering from a chest illness. Bach died on 1 January 1782 and he was buried in St Pancras churchyard one week later. His death “elicited obituaries particularly in German magazines.” John Bach left behind a substantial musical legacy, but also substantial debts. A benefit concert held on 27 May 1782 was unable to erase his debt, but Queen Charlotte personally got involved and Cecilia Bach was able to return to Italy via Paris in the summer of 1782. The music of J.C. Bach is probably more cosmopolitan and varied “than that of any other of the J.S. Bach’s son.” However, his reputation has severely suffered based on his own self-deprecatory remark, “My brother C.P.E. Bach lives to compose, I compose to live.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johann Christian Bach: Keyboard Sonata in C minor, Op. 17, No. 2 (Brigitte Haudebourg, harpsichord)