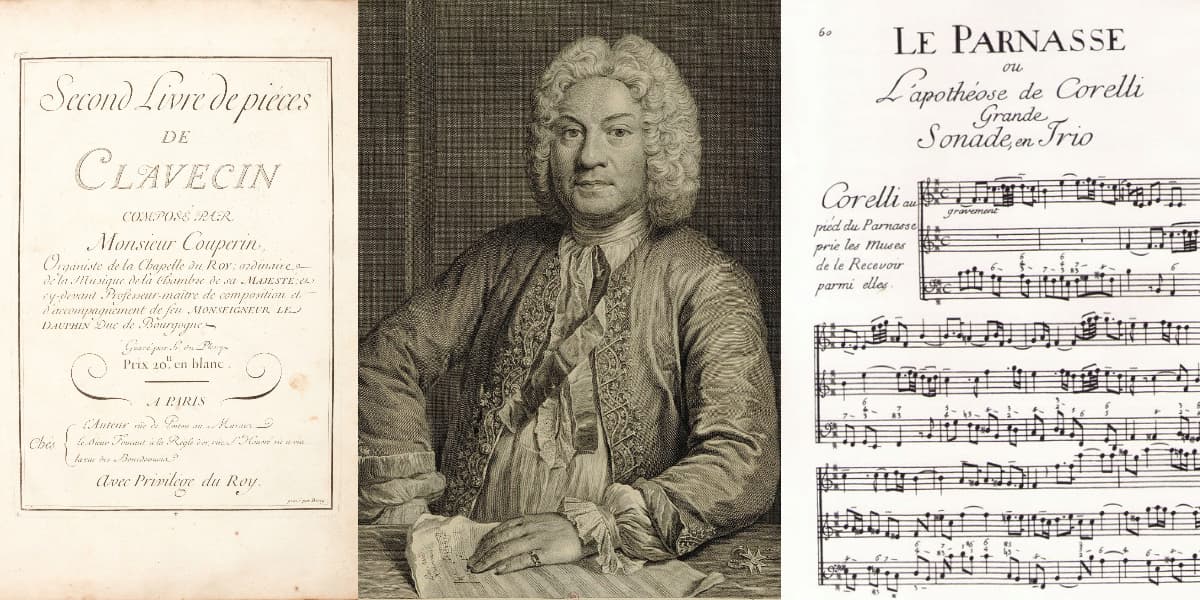

Historians frequently regarded François Couperin as “a composer of elegant trifles written for a sophisticated, yet frivolous, audience.” Charles Burney, for example, described Couperin’s music as “so crowded and deformed by beats, trills, and shakes, that no plain note was let to enable the hearer of them to judge whether the tone of the instrument on which they were played was good or bad.” While French music of the 17th and 18th century still presents an enigma to many listeners, both Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel described Couperin as “the epitome of French music.” After all, he would write some of the finest music of the French classical school, “far surpassing his contemporaries in his use of ambitious harmony, range, and melodic construction.” François, born on 10 November 1668 in Paris, belonged to one of the greatest dynasties of professional musicians. Active in and around Paris from the late 16th century to the mid-19th century, the Couperin family was closely linked with the church of St. Gervais, “where for 173 years members of the family occupied the organ loft.”

François Couperin: Pièces de clavecin, Book IV, 21 Ordre “La Couperin”

The Couperin family was officially chronicled at the beginning of the seventeenth century when the village lawyer Mathurin Couperin plied his trade at Beauvoir, in Brie. His son Denis eventually became a royal notary, while his other son, Charles, established himself as a tradesman in the neighboring town of Chaumes. By all accounts, Charles was an amateur musician, playing the organ at the parish church and the Benedictine abbey in the town. He was the grandfather of “Couperin le Grand,” a name attached to François to distinguish him from other members of the family, and three of his eight children became professional musicians.

In 1685 François Couperin was installed as organist at St. Gervais

Louis, François’s uncle, was born in 1626 and after relocating to Paris he took on the post of organist at St. Gervais and also played viol and violin in the ballet music of the court. Upon his early death, his brother Charles, François’s father, took over the organist post and established a family. Young François probably received his first musical instruction from his father, and when Charles died in 1679, he inherited the organist’s post from him.

François Couperin: Pieces de clavecin, Book 2: 8th Ordre in B Minor (excerpts) (Stefano Lorenzetti, harpsichord)

François was only ten, but the famous organist Jacques-Denis Thomelin, organist at St. Jacques-de-la-Boucherie and keyboardist to the King, took the boy under his wing. As had been agreed upon, François took over the musical reigns at St. Gervais in his eighteenth year. Four years later he married Marie Anne Ansault, who had influential family connections in the business world. In the year after his marriage, Couperin obtained his first royal privilege to print and sell his music. This license was valid for six years, and he lost no time in publishing a collection of organ pieces. As far as we know, this is the only organ music Couperin actually wrote down, although he was celebrated as a great improviser. A scholar writes, “it was as an organist that he first gained a foothold at court, being Louis XIV’s choice in 1693 as successor to his former teacher, Thomelin.” Couperin had only been seventeen when Archangelo Corelli published his first book of trio sonatas for two violins and basso continuo. Couperin’s admiration for the Italian master now inspired a set of trio sonatas.

François Couperin: Messe a l’usage ordinaire des paroisses (Mass for the Parishes) (Jean-Baptiste Robin, organ)

François Couperin has composed sets of Pièces de clavecin and trio sonatas

As Couperin would later write, “Charmed by the sonatas of Signor Corelli, whose works I shall love as long as I live, just as I do the French works of Monsieur de Lully, I attempted to compose one myself which I then had performed in the concert series where I had heard those of Corelli. Knowing the keen appetite of the French for foreign novelties above all else, and being unsure of myself, I did myself a very good turn through a little technical deceit. I pretended that a relation of mine, my cousin Marc-Roger Normand, in very truth in the service of the King of Sardinia, had sent me a sonata by a new Italian composer. I rearranged the letters of my name to form an Italian one, which I used instead. The sonata was devoured with eagerness, and I need not trouble to defend myself. However, I was encouraged. I composed others, and my italianized name brought me, in disguise, considerable applause. My sonatas, fortunately, won enough favour for me not to be in the least embarrassed by the subterfuge.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

François Couperin: Trio Sonata in C minor “La Visionnaire”