Hector Berlioz was born at 5pm on Sunday, 11 December 1803 in the small village of La Côte-Saint-André in the département of Isère. His father, Louis-Joseph Berlioz was a hardworking town physician who advocated such progressive cures as hydrotherapy and acupuncture. In fact, his treatise on acupuncture was published in 1816. He might have had a career of national prominence, but “instead chose to lead a life of quiet respectability in his native region.” He was remembered as “a generous and good man, particularly with regard to his concern for the poor.”

Berlioz as a child

As Hector would later write, “my father’s afflictions included a certain melancholia and a confirmed political and intellectual skepticism.” The composer’s mother, Marie-Antoinette-Joséphine, née Marmion, was described as “a strict Catholic and easily aroused to fits of temper,” but nevertheless she was the heart of the family, who sang her children lullabies and sentimental songs. Hector and his siblings grew up in a literate household that was supportive of the liberal arts. At the age of six, Hector was sent to the local seminary for elementary education but only stayed there for a couple of years. Starting from the age of ten, he was educated by his father at home.

Hector Berlioz: Recueil de romances (Stéphanie d’Oustrac, mezzo-soprano; Thibaut Roussel, guitar)

Berlioz apparently enjoyed reading books on travel and ancient legends, but he also became interested in composer biographies and some treatises on composition. He did receive some basic instructions on the flute and guitar, but he never studied the piano. Berlioz later commented that not playing the piano was actually an advantage, as it “saved me from the tyranny of keyboard habits, so dangerous to thought, and from the lure of conventional harmonies.” During the summer of 1815, the twelve-year-old boy met the eighteen-year-old niece of a neighbor, a young woman named Estelle Dubœuf.

Louis-Joseph Berlioz,

father of Hector Berlioz

Berlioz quickly developed a youthful crush, and he later described her hair, her good looks, and above all her pink boots. “She was standing on a rock, her hand resting on the trunk of a cherry tree, and seemed the embodiment of Florian’s Estelle, a pastoral romance he had recently read.” In his imagination, she became a literary conceit, and she knew nothing of his affections. “Her reaction upon learning of his love half a century later was one of perplexed amusement.”

Hector Berlioz: “Amitié, reprends ton empire” (Francoise Pollet, soprano; Anne Sofie von Otter, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Allen, baritone; Cord Garben, piano)

Enfolded by passion, Berlioz began to take first music lessons with M. Imbert, second violinist in the pit orchestra of the Lyon theatre. He had been hired by Joseph Berlioz and other prominent townspeople to provide music lessons for twelve students in town and to instruct and rehearse the National Guard band. By all accounts, Imbert was a kind man and successful teacher who established an active society of chamber musicians. Berlioz started to write chamber music for them, especially quartets, quintets, and arrangements of popular songs. According to a biographer, “his first extended composition was a potpourri concertant sur des themes italiens for flute, horn, two violins, viola, and cello, written perhaps in early 1818.” Berlioz offered this composition to two Parisian publishers, but he was rejected. He followed up with a selection of songs, and some of these musical ideas would later resurface in more mature compositions. As his interest in music increased, so did his father’s insistence that he study medicine. It was agreed that he would travel to Paris to prepare for a medical career.

Hector Berlioz: 8 Scènes de Faust, Op. 1 (Angelika Kirchschlager, mezzo-soprano; Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, tenor; Frédéric Caton, bass; Radio France Choir; Claude Zibi, guitar; Radio France New Philharmonic Orchestra; Yutaka Sado, cond.)

Hector Berlioz, 1839

For the first couple of weeks in Paris, Berlioz was disoriented and confused. However, he was soon invited to cotillions and soirées, and found companionship in a circle of young intellectuals. He also ventured to the Opéra, and within a couple of weeks, he had seen works by Salieri, Méhul, and Boieldieu. He was also able to fulfill one of the dreams of his childhood and saw Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride. Berlioz discovered the masterworks of Spontini, Rossini, Auber, and Meyerbeer, and the true aversion to the study of medicine and his love for music and poetry is detailed in his memoirs.

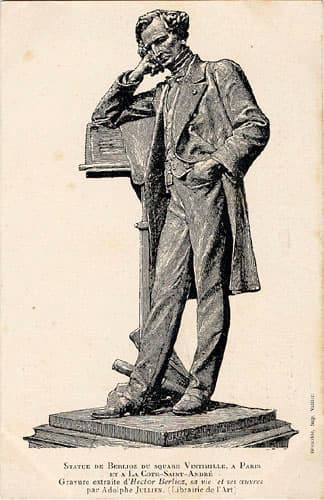

Statue of Berlioz in Paris and La Côte-Saint-André

He writes, “Become a doctor! Study anatomy! Dissect! Take part in horrible operations instead of giving myself body and soul to music, sublime art whose grandeur I was beginning to perceive! Forsake the highest heaven for the wretchedest regions of earth, the immortal spirits of poetry and love and their divinely inspired strains for dirty hospital orderlies, dreadful dissection-room attendants, hideous corpses, the screams of patients, the groans and rattling breath of the dying! No, no! It seemed to me the reversal of the whole natural order of my existence. It was monstrous. It could not happen.” Berlioz pursued his medical studies for just over a year, and a complete break with his family plunged him into an archetypal struggle, not only for financial survival but also for the acceptance of his artistic ideas.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Hector Berlioz: “Overture” to Les francs-juges, Op. 3