Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826) was suffering from the advanced effects of tuberculosis when he received a letter from the impresario Charles Kemble in London on 18 August 1824. The letter issued an invitation to come to London and compose and direct a new opera for the following season. Weber’s doctors were strictly against such a journey and warned him that he could only expect a few more months, or perhaps weeks, of life. Looking at the financial benefits, however, Weber accepted the commission.

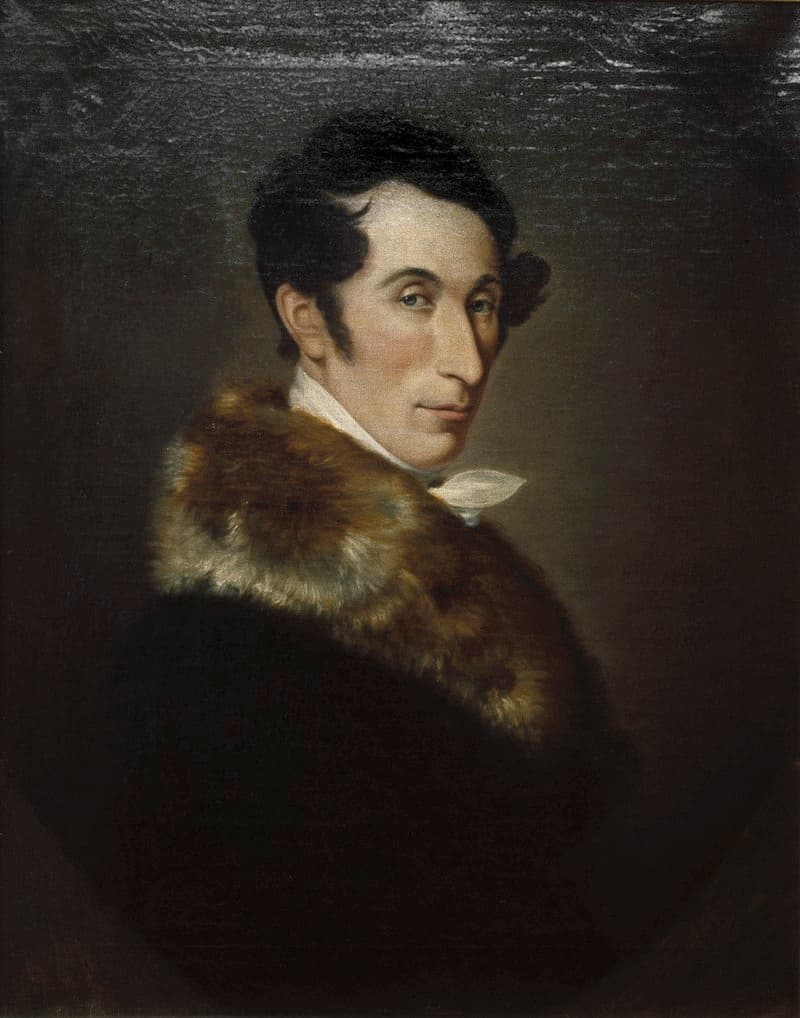

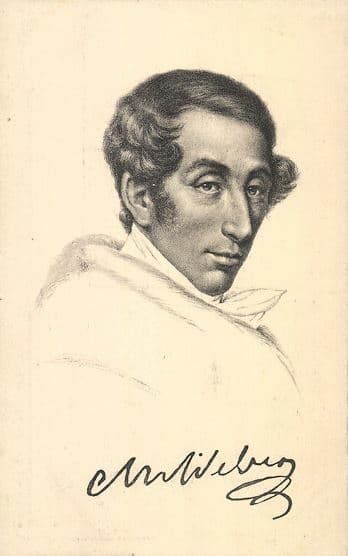

Carl Maria von Weber

In order to prepare for his London adventure, Weber began an intensive study of English in October 1824, and he took 153 lessons in all. He was also given the choice of opera subjects in Faust or Oberon, and once he had decided on the latter, the British dramatist James Robinson Planché crafted the words of the only English opera ever set by Weber. When the libretto had not arrived in December 1824, it was quickly decided that the opera would have to be postponed until the 1826 season.

Carl Maria von Weber: Oberon, “Ouverture”

Once the libretto had finally arrived, Weber was concerned with the nature of the writing and he commented to Planché. “The intermixing of so many principal actors who do not sing, the omission of the music in the most important moments, all these things deprive our Oberon the title of an opera, and will make him unfit for all other Theatres in Europe; which is a very bad thing for me, but passons la dessus.”

Lucia Elisabeth Vestris as Fatima in Oberon

Weber understood that the libretto catered to English tastes and that a German version would be in need of major revision. Weber had composed the bulk of the opera when he departed for London via Paris. He made an unannounced visit to Rossini, who records, “I am shocked at finding him so pale and wasted, coughing so much and exhausted by the efforts of climbing the stairs.” Rossini did his best to dissuade him from the London trip, but after seeing a number of productions and being visited by Cherubini twice, Weber was finally on his way to London. Weber was received like royalty as he writes, “Could one expect or hope for more enthusiasm, more affection? Are these the ‘cold’ English welcoming me?

Carl Maria von Weber: Oberon, J. 306 – Act II: Ariette: Arabiens einsam Kind (Vesselina Kasarova, mezzo-soprano; Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; Marek Janowski, cond.)

Rehearsals for Oberon began on 9 March, but several of the solo numbers were still missing. Amid exhausting rehearsals, concerts, and social engagement, Weber penned arias for the immensely popular tenor John Braham, Mary Ann Paton, and Lucia Elizabeth Vestris. Once Weber had put the finishing touches on the overture, Braham requested a substitute aria, and at the very last minute Braham also wanted another aria to “show off a different quality in his voice.”

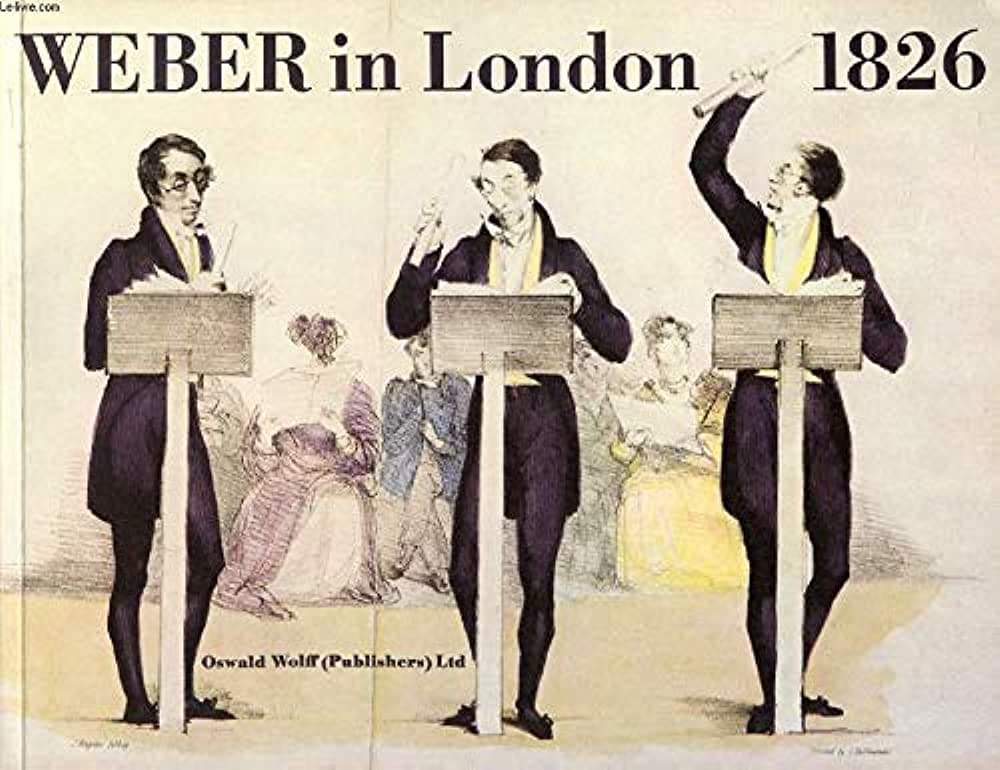

Weber in London, 1826

A biographer writes, “By the beginning of April Weber had sunk even lower physically, with severe chest constriction, fever, and diarrhea, and consumed with homesickness. His face drained of colour, his hands shook so violently that he could hardly feed himself and could only manage a glass if it were half filled, his feet were so swollen that he could not get into his smart shoes and stocking in order to attend receptions. On the day of the final rehearsal, a piece of scenery fell on Ann Paton’s head and the rehearsal had to finish without her.

Carl Maria von Weber: Oberon, J. 306 – Act I: Eil, edler Held! (Inga Nielsen, soprano; Vesselina Kasarova, mezzo-soprano; Berlin Radio Chorus; Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin; Marek Janowski, cond.)

The first twelve performances of Oberon had been sold out for weeks, and when Weber appeared on the evening of 12 April, “the audience rose to him, shouting and cheering, waving hats and handkerchiefs, while the orchestra tapped their violins with their bows, a custom unfamiliar for him and whose sound seems to have bewildered him.” The première on 12 April was an enormous success; the overture was encored, as were all the individual numbers, some twice.

Carl Maria von Weber

Weber immediately made plans for revising the work on his return to Germany, however, his health had greatly deteriorated. He was now obsessed with thoughts of home, and he was only able to rouse himself to bursts of activity even when completely limp with fatigue. Weber died, at the age of 39, in his sleep during the night of 5 June 1826 at the home of his good friend and host Sir George Smart. As a scholar writes, “It is a remarkable testimony to Weber’s operatic genius that, notwithstanding the unmitigated awfulness of its libretto, Oberon has maintained a toe-hold in the repertory. The imaginative and expressive quality of his writing for the principals invests them with a depth of characterization far beyond the implications of the text, while his sensitivity to colour and atmosphere in the orchestral and concerted numbers lifts the work above the level of shallow pantomime suggested by its libretto.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Carl Maria von Weber: Oberon, “Ocean! Thou mighty monster!”