George Frideric Handel

The Fishamble Street Musick Hall in Dublin was abuzz with jittery electricity on 13 April 1742. The musical superstar George Frideric Handel was ready to present his oratorio Messiah to the public, and the audience reached a record 700 listeners. In fact, management had pleaded with “ladies to wear dresses without Hoops, and gentlemen were requested to remove their swords” in order to free up space for more patrons.

The Fishamble Street Musick Hall in Dublin

Handel and his music were not the only draw on this day, however, as the celebrated English singer and actress Susannah Maria Cibber, the sister of composer Thomas Arne, was to feature on stage as well. She was universally admired for her ability to move her audiences emotionally, but she was also involved in a rather scandalous marriage to actor Theophilus Cibber. Her husband was said to have been abusive and a big spender, “even selling off some of his wife’s wardrobe and personal effect to pay his creditors.” The couple had taken in a wealthy tenant named William Sloper, and it is said that Cibber forced his wife at gunpoint to sleep with Sloper in order to gather testimony for a lawsuit accusing Sloper of “assaulting, ravishing and carnally knowing his wife.” Cibber did win the court case, but in the event, Susannah and Sloper ran off together and had a daughter.

George Frideric Handel: Messiah “Part 1”

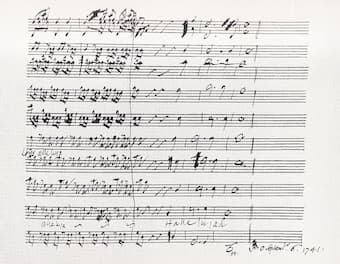

Score of Hallelujah Chorus from Messiah

Once the performance got underway, “men and women in attendance sat mesmerized from the moment the tenor followed the mournful string overture with his piercing opening line: “Comfort ye, comfort ye my people, saith your God.” Soloists alternated with wave upon wave of chorus, until, near the midway point, Cibber intoned: “He was despised and rejected of men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.” So moved was the Rev. Patrick Delany that he leapt to his feet and cried out: “Woman, for this be all thy sins forgiven thee!” The Dublin notices were full of praise for Cibber’s acting and her singing, with a critic writing, “What then must the mighty force of oratorical expression be, when conveyed to the heart with all the superadded powers and charms of musick? No person of sensibility, who has had the good fortune to hear Mrs Cibber sing the oratorio of the Messiah, will find it very difficult to give credit to accounts of the most wonderful effects produced from so powerful a union.”

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, “He was despised”

Charles Jennens

Handel had completed the score, to a libretto by Charles Jennens, in a breathtaking 24 days. From the beginning of the project Jennens was overjoyed and wrote to a friend, “I hope Handel will lay out his whole genius and skill upon it, that the composition may excel all his former compositions, as the subject excels every other subject.” There are several reasons why Handle selected the city of Dublin for the premiere of Messiah. For one, as a critic writes, “Handel had been downcast by the apathetic reception that London audiences had given his works the previous season. He did not want to risk another critical failure, especially with such an unorthodox piece.” Secondly, Handel had received an invitation from the Duke of Devonshire, who was serving as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. In addition, Handel’s violinist friend Matthew Dubourg, was in Dublin as the Lord Lieutenant’s bandmaster. Thirdly, Dublin was one of the fastest-growing and most prosperous cities in Europe, “with a wealthy elite eager to display its sophistication and economic clout to stage a major cultural event.” To be sure, Handel did not inform Jennens as he wrote, “it was some mortification to me to hear that instead of performing Messiah here he has gone into Ireland with it.”

George Frideric Handel: Messiah, HWV 56 (1751 Version) (Henry Jenkinson, treble; Otta Jones, treble; Robert Brooks, treble; Iestyn Davies, counter-tenor; Toby Spence, tenor; Eamonn Dougan, bass; Oxford New College Choir; Academy of Ancient Music; Edward Higginbottom, cond.)

Statue of Handel

Handel arrived in Dublin on 18 November 1741, and he arranged a subscription series of six concerts, immediately followed by a second series. By early March, Handel was scouting for locations and was given permission to use the choirs of two cathedrals for the occasion. The performing forces totaled sixteen men and sixteen boy choristers, and the women soloists were Christina Maria Avoglio, and Susannah Cibber. To accommodate the range of his singers, Handel made some last minute alterations, and the premiere performance in Fishamble Street Hall was announced for 12 April, but eventually given one day later. The premiere benefitted three charities, and it earned unanimous praise from the assembled press. “Words are wanting to express the exquisite delight it afforded to the admiring and crowded Audience.”

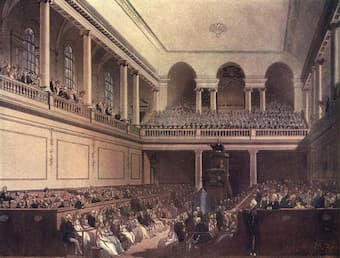

Foundling Hospital

Handel remained in Dublin for four months after the premiere, and he organized a second performance of Messiah on 3 June. Even more impressive, the success in Dublin was quickly repeated in London, particularly in the chapel of the Foundling Hospital. Messiah became Handel’s best-known composition and Mozart re-orchestrated the work in 1789, insisting that “any alterations to Handel’s score should not be interpreted as an effort to improve the music.” And Beethoven famously proclaimed Handel to be the “greatest composer that ever lived.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

George Frideric Handel: Messiah “Part 3”