Arturo Toscanini and Giacomo Puccini, 1910

Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) saw Victorien Sardou’s play La Tosca in Florence in 1895 with Sarah Bernhardt in the leading role. He immediately envisioned an opera without excessive proportions or a decorative spectacle, nor one that called for a superabundance of music.

Giuseppe Giacoso

Unfortunately Sardou had granted the rights to the librettist Luigi Illica and the composer Alberto Franchetti, however, the publisher Ricordi quickly persuaded Franchetti to withdraw from the project. The versification was now in the hands of Giuseppe Giacoso, who initially complained, “there was too much plot, and too little room for lyrical expansion.” With the completed libretto in hand, Puccini set to work on establishing the authenticity of certain details. His friend Father Pietro Panichelli supplied information on plainsong melodies, the correct order of the cardinal’s procession and the costumes of the Swiss Guard. He even “learnt the exact pitch of the great bell of St. Peter’s, and he made a special journey to Rome to hear the matins bells from the ramparts of the Castel Sant’ Angelo.”

Terfel: Tosca, “Te Deum”

Elvira Puccini, Giacomo Puccini, Antonio Puccini

The opera was completed in October 1899, and Puccini’s publisher Ricordi arranged the première in the Italian capital on 14 January 1900. Critical reception was mixed, as some reviewers objected to the brutality of the plot. Nevertheless, the opera ran for 20 evenings in Rome, and two months later in Milan under Toscanini. The first foreign performance was given at Buenos Aires in June the same year, followed on 12 July by the London première, at Covent Garden, Despite its popular success, Tosca did receive fiery opposition on account of its swift and naturalistic action. Misleadingly labeled ‘verismo,’ the opening act introduces Cesare Angelotti, who escaped political imprisonment and is seeking refuge in his family’s chapel. The sacristan, meanwhile, banters with the painter Mario Cavaradossi, who is finishing a portrait of Mary Magdalene.

Giuseppe Zocchi: View of the Tiber Looking Towards the Castel Sant’Angelo, with Saint Peter’s in the Distance

In his painting, he has succeeded in blending the charms of his beloved Tosca with the blonde beauty of an unknown woman—actually Angelotti’s sister– whom he has often observed at prayer in the church. Angelotti greets his friend and political ally, but the singer Floria Tosca interrupts their conversation. The portrait of Mary Magdalene arouses Tosca’s jealousy, but she is eventually appeased by Cavaradossi’s assurances. Angelotti’s escape is discovered and the chief of police, Baron Scarpia enters the church with his lieutenant Spoletta. They find evidence of Angelotti’s presence, interrogate the sacristan and Cavaradossi, and Scarpia passionately declares his love for Tosca.

Callas: Tosca, “Vissi d’Arte”

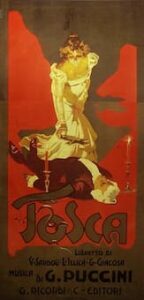

Tosca (1899)

At the beginning of the second act, Scarpia rejoices at having captured Cavaradossi, but the painter refuses to denounce his friend. Tosca, who is forced to listen to her lover’s screams of agony under torture, finally divulges Angelotti’s hiding place. She asks for the price of Cavaradossi’s freedom, and Scarpia demands her body. News arrive that Angelotti has committed suicide, and Tosca accepts Scarpia’s proposal. Scarpia orders a mock execution, and after penning a safe-conduct note, is killed by Tosca. She arranges Scarpia’s body for funeral and departs to the sound of distant and ominous drums. The final act finds Cavaradossi awaiting his execution. He manages to write a note to Tosca, who arrives with Spoletta. She tells him how she killed Scarpia, and explains the mock execution. When the firing squad leaves, the tragic truth, however, is revealed. Scarpia had never intended to keep his word and Cavaradossi is dead. In the meantime, Scarpia’s murder has been discovered, and before Spoletta is able to arrest Tosca, she leaps to her death.

Pavarotti: Tosca, “E Lucevan le stelle”

Cover of the libretto for Tosca

Tosca is the most Wagnerian of Puccini’s operas. It musically relies on a web of musical Leitmotivs, which identify objects, ideas and people, although none of them is developed or modified. In addition, they also provide us with glimpses of a character’s thoughts and emotional state. Puccini’s musical language, featuring diatonic melodies and successions of unrelated chords, perfectly compliments the theatrical and dramatic aspects of the work. Puccini’s sophisticated style of orchestration cleverly aligns specific instrumental groups and orchestral timbres to match distinct dramatic moments, or to establish atmospheric backgrounds. Scholars consider the only weakness in the drama to be “Puccini’s inept handling of the political elements; but issues of this kind held no interest for the composer.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gheorghiu: Tosca, “Final Scene”