Arturo Toscanini

On New Year’s Day 1957, Arturo Toscanini suffered a stroke. Unable to recover, he passed away on 16 January at the age of 89 at his home in the Riverdale section of the Bronx in New York City. His body was transferred to Milan, and his epitaph is taken from his remarks concluding the 1926 premiere of Puccini’s unfinished Turandot. “Here the opera ends, because at this point the maestro died.” For a good many people, Toscanini was a god who could do no wrong. Charismatic to the point of ruthlessness, he kicked Mahler out of New York City and in the process entrenched an essentially modern performing style—faster tempos, less rubato, and away from musically milking individual phrases to instead fixate on the structural architecture of the music. His ear for orchestral detail and color combined with an almost overbearing sense of perfection and intensity, and “his insistence on the primacy and purity of the musical text, made him one of the great cult figures of his time.”

Toscanini: Ride of the Valkyries

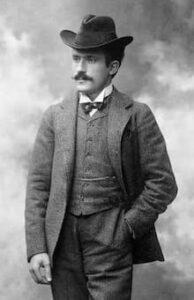

Arturo Toscanini, c. 1900

Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) had trained to be a cellist at the Parma Conservatory. He also studied piano and composition, and from an early age was known for “a prodigious musical memory and ear, insatiable curiosity, great powers of concentration, and a dominating and uncompromising character alike.” During a tour in Brazil in 1886, Toscanini was called upon to take over a performance of Aida in Rio de Janeiro. Apparently, he conducted, without a score, in masterly fashion, and achieved a success from which there could be no turning back.” Toscanini built a reputation as a powerful and exacting conductor, who above all championed Wagner, whom he called “the greatest composer of the century.” Toscanini was a fierce enemy of complacency, mediocrity, and routine, and he had the temper to prove. I could completely fly off the handle at the slightest provocation, or musical inattention. “He demanded precise playing and was plunged into despair over a single lapse. He insisted that any musician, no matter how famous, who did not share his attitude be fired. He would sooner quit than tolerate the slightest lapse in standards.”

Richard Strauss: Death and Transfiguration (NBC Symphony Orchestra; Arturo Toscanini, cond.)

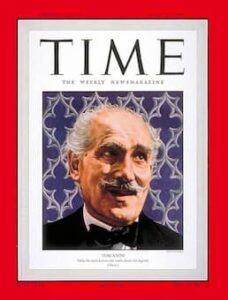

Toscanini on Time Magazine, 1948

It has been written that “Energy, single-mindedness, impetuosity combined with an inflexible will, fanatical perfectionism, and an almost morbid self-criticism were among Toscanini’s most remarkable characteristics.” In short, it was Toscanini’s way or the highway. His musical interpretations grew from the composer’s score, which he considered the ultimate authority. For his admirers Toscanini objectively and faithfully interpreted the composer’s intentions. His electric intensity produced interpretations “that gave the impression of being conceived and carried out as single organic wholes: they seemed in some mysterious way to relive the fiery moment of the music’s actual creation.” He certainly had a tremendous sense of musical architecture and rhythmic continuity. As a scholar writes, “his feeling for the singing line and the wide-spanned arch of melody was irresistible and exerted a magnetic power over orchestras.”

Johannes Brahms: Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a, “St. Anthony Variations” (NBC Symphony Orchestra; Arturo Toscanini, cond.)

Arturo Toscanini caricature

by Enrico Caruso

Toscanini featured three times on the cover of Time Magazine and he was idolized by musicians, critics and the public. Younger generations have been less complimentary, and assert that Toscanini actually did great harm to 20th-century composers in general, and American composers in particular. Toscanini has also been criticized for his rhythmically too rigid performances that have been likened to the mechanical exactitude of a metronome. But what really rubs a good many current commentators the wrong way, was Toscanini’s unshakable belief that no performer had the right to deflect attention from the composer; the music needed to speak for itself. Above all, however, “Toscanini stunned the musical world with a new style which proved so influential that it became the interpretive norm… his objectivity startled the musical world with its simple effectiveness and paved the way to our modern standards of interpretation.”

Gioachino Rossini: Italian Girl in Algiers – Act I: Overture (New York Philharmonic Orchestra; Arturo Toscanini, cond.)

Toscanini conducting Verdi’s Hymn of Nations

Much of the current revisionism is focused on Toscanini’s cult status rather than on his achievements as a conductor. And that achievement is preserved in huge number of recordings, many of them digitally restored. He made his first recordings in December 1920 with the La Scala Orchestra in the Trinity Church studio of the Victor Talking Machine Company in Camden, New Jersey, and his last with the NBC Symphony Orchestra in June 1954 in Carnegie Hall. “Toscanini’s extraordinary genius,” as one scholar puts it, “remains one of the great phenomena of the history of musical performance in the last 100 years, and marks a highpoint in the development of the conductor’s art.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Toscanini: “Act IV” Rigoletto