Friedrich Gulda

Pianist Friedrich Gulda is commonly regarded as the “cross-over” pioneer of his time. Known for his extraordinary interpretations of the music of Bach, Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven, he freely cultivated an interest in jazz and composition. Stylistic references to jazz gave way to improvisations and arrangements of the popular-music repertory. Teaming up with the likes of jazz great Chick Corea, Gulda uncompromisingly expressed his anti-bourgeois artistic convictions by jarringly juxtaposing elements and styles borrowed from jazz, folksong, electronic music and the classical music repertory. It is hardly surprising that in classical circles he earned the nickname “terrorist pianist,” a moniker Gulda was predictably rather proud of. Gulda was born on 16 May 1930 in Vienna, the second child of Friedrich Johann Gulda and Marie Aloysia Gulda, née Súttay. He received his first piano lessons at the Viennese Conservatory at the age of seven. In contrast to his elder sister, Hedwig, who gave up her piano lessons after just one year, Friedrich Gulda (or Fritz as his parents called him) continued his lessons and received private instruction from Professor Felix Pazovsky starting in 1937.

Friedrich Gulda: Piano Variations (Friedrich Gulda, piano)

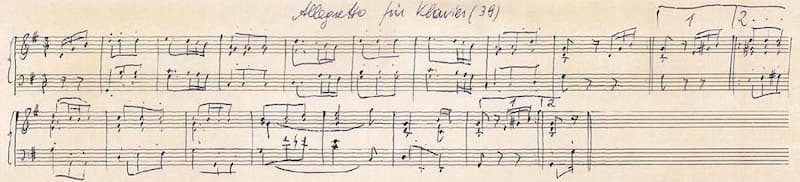

Gulda produced his first composition, an “Allegretto for piano” at the age of nine, and in 1942 he completed the entrance examination for the Viennese College for Music. He studied piano with Bruno Seidlhofer and music theory with Joseph Marx. During his first year of study, Gulda first performed in public as part of a College concert on 20 December 1942, performing a Scherzo and Impromptu by Schubert. Two years later, on 24 June 1944, Gulda featured in the Schumann piano concerto with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. During the war, Gulda and his friend Joe Zawinul “would perform forbidden music including jazz, in violation of the government’s prohibition on the playing of such music.” Gulda spent the end of the war with his mother in a small village southeast of Vienna, where he trained the local choir and acted as the church organist. His father returned to Vienna in September 1945, after being released from captivity as a Russian prisoner of war.

Gulda produced his first composition, an “Allegretto for piano” at the age of nine, and in 1942 he completed the entrance examination for the Viennese College for Music. He studied piano with Bruno Seidlhofer and music theory with Joseph Marx. During his first year of study, Gulda first performed in public as part of a College concert on 20 December 1942, performing a Scherzo and Impromptu by Schubert. Two years later, on 24 June 1944, Gulda featured in the Schumann piano concerto with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra. During the war, Gulda and his friend Joe Zawinul “would perform forbidden music including jazz, in violation of the government’s prohibition on the playing of such music.” Gulda spent the end of the war with his mother in a small village southeast of Vienna, where he trained the local choir and acted as the church organist. His father returned to Vienna in September 1945, after being released from captivity as a Russian prisoner of war.

Gulda Plays Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23, K. 488

Friedrich Gulda and Martha Argerich

In 1946, 354 participants took part in the International Music Competition in Geneva. Among them was a small group of hungry and scared musicians from Austria. Gulda was only 15 at the time, and he played Bach, the Beethoven Sonata Op. 111, and Debussy “Feux d’artifice.” Gulda certainly made a big impression, but the jury initially favored the Belgian pianist Lode Backx. When the final vote was taken, Gulda was declared the winner. One of the jurors, Eileen Joyce, stormed out in rage claiming that Gulda supporters had unfairly influenced the other jurors. Gulda received a hero’s welcome back in Vienna, and he performed Beethoven’s 4th Piano Concerto with the Vienna Philharmonic at the Concert of the Austrian Prize Winners from the International Music Competition in Geneva 1946. On 10 December 1946, Gulda played his first solo recital in Vienna, performing works by Bach, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin, Debussy and Prokofiev.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 31 in A-Flat Major, Op. 110 (Friedrich Gulda, piano)

Friedrich Gulda: Allegretto for piano, 1939

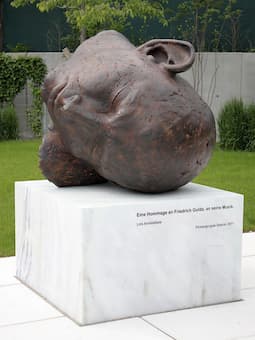

Statue of Friedrich Gulda

During 1948, Gulda performed close to 30 concerts across Europe, and in 1949 he toured South America playing 37 concerts in Rio de Janeiro, Sào Paolo, Montevideo and Buenos Aires. His debut at Carnegie Hall in New York took place on 11 October 1950, and Gulda gathered his first impressions of live jazz performances at the New York “Birdland” club. Highly sought after as a piano teacher, his students included Martha Argerich and Claudio Abbado. However, Gulda openly began to flaunt classical music etiquettes and conventions, playing some recitals in the nude. He certainly had a strong dislike of authority, as he refused to accept the “Beethoven Ring” offered by the Vienna Academy in recognition of his performances and recordings. His concert programs increasingly combined jazz, free improvisation and classical music. He once said, “There can be no guarantee that I will become a great jazz musician, but at least I shall know that I am doing the right thing. I don’t want to fall into the routine of the modern concert pianist’s life, nor do I want to ride the cheap triumphs of the Baroque bandwagon.” Gulda strongly believed that all music had worth, regardless of how society judges it. He famously said, “Play every tone as if your life depends on it! For your life really does depend on it.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Friedrich Gulda Plays Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No.5 “Emperor”

Thank you! The most beautiful classical music of Mozart that I have ever heard.

It brings tears of joy.

I know nothing of this artist. This presentation was fascinating

Agree

I love his DGG recordings of # 20 and 21!

He left his mark with originality.

I love following the growth of this artist from his early renditions of the classics to his later ones. He is/was a genius . Just love him for what he attempted to do.