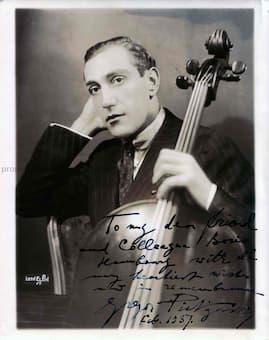

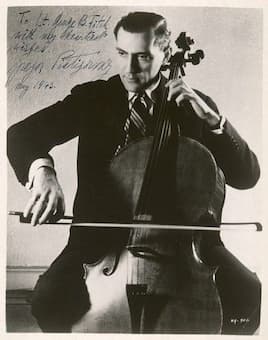

Gregor Piatigorsky

For several decades in the mid-twentieth century, Gregor Piatigorsky (1903-1976) was the undisputed cello superstar. Some say, that he “was the greatest string player of all time, possessing a glorious low-register sound characterized by a distinctive fast and intense vibrato.” He was able to execute with consummate articulation all manner of extremely difficult bowings, and his wonderful musical imagination led him to explore the subtlest shades of articulation. Some of the greatest composers of his day composed dedicated works for him, including Sergei Prokofiev, Paul Hindemith, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, William Walton, Vernon Duke, and Igor Stravinsky. A delightful anecdote tells that at a rehearsal of Richard Strauss’ Don Quixote, which Piatigorsky performed with the composer conducting, after the dramatic slow variation in D minor, Strauss announced to the orchestra, “Now I’ve heard my Don Quixote as I imagined him.” Piatigorsky was a warm and deeply expressive musician who took “cello technique to dazzling new heights.”

Piatigorsky Plays Chopin’s Sonata, 2nd Movement

Gregor Piatigorsky was born in Ekaterinoslav, currently Dnipropetrovsk in Ukraine, on 17 April 1903. He received violin and piano lessons from his father, but when he saw and heard the sounds of the cello at an orchestra concert, he was determined to become a cellist. Piatigorsky took up the instrument in earnest at the age of seven, but he was not considered a child prodigy. In fact, a student of the famed German cellist Julius Klengel told him that he had no talent whatsoever. Piatigorsky ignored his advice and won a scholarship at the Moscow Conservatory, studying with Gubariov, von Glehn, and Brandoukov. The October Russian Revolution took place when he was only 13, and he became member of a string quartet. Apparently, Piatigorsky objected to the name “Lenin Quartet,” and he supposedly had a lengthy discussion with Lenin himself as to why it should be called the “Beethoven Quartet.” In the event, Piatigorsky was hired as the principal cellist for the Bolshoi Theater at the age of 15.

Gregor Piatigorsky was born in Ekaterinoslav, currently Dnipropetrovsk in Ukraine, on 17 April 1903. He received violin and piano lessons from his father, but when he saw and heard the sounds of the cello at an orchestra concert, he was determined to become a cellist. Piatigorsky took up the instrument in earnest at the age of seven, but he was not considered a child prodigy. In fact, a student of the famed German cellist Julius Klengel told him that he had no talent whatsoever. Piatigorsky ignored his advice and won a scholarship at the Moscow Conservatory, studying with Gubariov, von Glehn, and Brandoukov. The October Russian Revolution took place when he was only 13, and he became member of a string quartet. Apparently, Piatigorsky objected to the name “Lenin Quartet,” and he supposedly had a lengthy discussion with Lenin himself as to why it should be called the “Beethoven Quartet.” In the event, Piatigorsky was hired as the principal cellist for the Bolshoi Theater at the age of 15.

Sergei Prokofiev: Cello Sonata in C Major, Op. 119 (Gregor Piatigorsky, cello; Rudolf Firkušný, piano)

Heifetz, Rubinstein and Piatigorsky

Piatigorsky was eager to further his studies in the West, but Soviet authorities flatly refused his request. Anatoly Lunacharsky had been appointed Commissar of The People’s Commissariat for Education, and he was in charges of dealing with musicians. Piatigorsky was on good terms with Lunacharsky, and he repeatedly asked him for permission to leave. Yet, he was always denied and told “that he was needed in Moscow.” Piatigorsky, however, would not be denied and he defected into Poland by taking a cattle train to the frontier, and then fleeing across the border with his cello. The story goes that border guards started to shoot at him and his companions, including a voluptuous opera singer, when they were crossing a river. When the soprano heard the shots, “she grabbed Piatigorsky and crushed his cello in the process.” Everybody remained unhurt, but the cello did not survive. Piatigorsky enjoyed initial success with the Warsaw Philharmonic, with a critic writing, “Piatigorsky from Moscow is a young artist undoubtedly extremely talented and very advance in technique. His sound is enormously resonant and clean… and he captured our hearts.” He remained in Warsaw for the conclusion of the orchestral season before relocating to Germany to study with Hugo Becker and Julius Klengel.

Maurice Ravel: Piano Trio in A Minor (Arthur Rubinstein, piano; Jascha Heifetz, violin; Gregor Piatigorsky, cello)

Piatigorsky remembered, “Becker was the first and only teacher I had to pay for lessons; he charged a great deal.” The relationship between Becker and Piatigorsky was an uneasy one, but Becker favorably compared him to cellist Emanuel Feuermann, “Piatigorsky’s talent lies more in the direction of the emotional, while Feuermann in that of dexterity.” In the fall of 1922, Piatigorsky decided to study with the other major icon of the cello, Julius Klengel, in Leipzig. He was accepted as a private student, and remembers, “After spending a little more time in Berlin, I went to see Klengel and tried to find my happiness in Leipzig. Leipzig, just as Berlin, did not excite me at all. Unfriendly boarding houses aside, I really liked Klengel, at least as a person. After seeing him, I was pretty sure that I will finally learn something new, and started practicing. After I played for him, he was so amazed that he did not want me to study with him. He based his decision on the fact that he thought that I was a complete, grown artist and he could not teach me anything I did not already know…Truthfully, I would have liked it a lot more if he criticized me.” Life in Berlin was extremely difficult, and to earn a living Piatigorsky played in a trio in a Russian café in Berlin. Lady luck finally smiled on him when the conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler heard him play and arranged an audition for principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonic. Piatigorsky was given the post, which he held until 1929, and until he decided to pursue a career as a traveling concert artist.

Piatigorsky remembered, “Becker was the first and only teacher I had to pay for lessons; he charged a great deal.” The relationship between Becker and Piatigorsky was an uneasy one, but Becker favorably compared him to cellist Emanuel Feuermann, “Piatigorsky’s talent lies more in the direction of the emotional, while Feuermann in that of dexterity.” In the fall of 1922, Piatigorsky decided to study with the other major icon of the cello, Julius Klengel, in Leipzig. He was accepted as a private student, and remembers, “After spending a little more time in Berlin, I went to see Klengel and tried to find my happiness in Leipzig. Leipzig, just as Berlin, did not excite me at all. Unfriendly boarding houses aside, I really liked Klengel, at least as a person. After seeing him, I was pretty sure that I will finally learn something new, and started practicing. After I played for him, he was so amazed that he did not want me to study with him. He based his decision on the fact that he thought that I was a complete, grown artist and he could not teach me anything I did not already know…Truthfully, I would have liked it a lot more if he criticized me.” Life in Berlin was extremely difficult, and to earn a living Piatigorsky played in a trio in a Russian café in Berlin. Lady luck finally smiled on him when the conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler heard him play and arranged an audition for principal cellist of the Berlin Philharmonic. Piatigorsky was given the post, which he held until 1929, and until he decided to pursue a career as a traveling concert artist.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Piatigorsky Plays Walton’s Cello Concerto