François-Louis Gounod

Charles Gounod, born on 17 June 1818 in Paris, is primarily remembered as the composer of the opera Faust and an Ave Maria descant to the first prelude of J.S. Bach’s C-major prelude from the WTC. Yet in his day, he was one of the most respected and prolific composers in France. Scholars suggest, “his musical influence on the course of French music was highly significant, but in the fractured post-Wagnerian critical climate towards the end of his life, his reputation took a severe hit.”

Gounod in his youth

He was born in the Latin Quarter of Paris, the second son of François Louis Gounod and his wife Victoire, née Lemachois. His father was a painter and engraver of considerable talent, and like two generations of ancestors, worked for royalty. According to the composer, “his father was prevented from achieving greater fame only by modest ambition.” His mother, born at Rouen, was a talented pianist who had studied piano with Louis Adam. Shortly after Charles’s birth François was appointed official artist to the Duc de Berry, a member of the royal family, and Charles spent his early years at the Palace of Versailles, where the family was allotted an apartment.

Charles Gounod: Messe brève et salut in G Major, Op. 1, “Mass No. 2” (Brassus Choral Society; François Margot, organ; Andre Charlet, cond.)

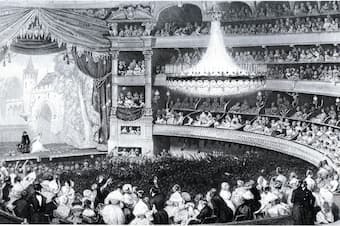

Théâtre-Italien in Paris, c. 1840

When François died prematurely in 1823, Victoire established a piano teaching studio to support her two sons. In his autobiography, Gounod writes, “My mother, who nursed me herself, had certainly given me music with her milk. She always sang while she was nursing me, and I can say that I took my first lessons unconsciously… I acquired a very clear idea of the various intonations, of the musical intervals they represent, and of the elementary forms of modulation… Thus my ear was thoroughly practiced.” His mother invited a local musician to pass judgment on the boy’s musical abilities, “and he put me in the corner of the room, with my face to the wall, and sitting down at the piano improvised a succession of chords and modulation. At each change he would ask what key am I playing, and I never made a single mistake in all my answers.” As Gounod writes, “my mother was triumphant. Little did she dream, when she took me, a six-year-old boy, to the Odeon to hear “Robin Hood,” that she had stirred my first impulse toward the art that was to govern all my life.”

Charles Gounod: “Le soir” (Annette Betanski, soprano; James Sommerville, horn; Rena Sharon, piano)

Antoine Reicha

When his mother’s health began to fail, Gounod was sent to various boarding schools in Paris. By all accounts, he was a good student and excelled in Latin and Greek. His mother always remained hopeful that Gounod would secure a career as a lawyer, “but his interest were in the arts. He was outstandingly musical and highly talented painter.” Dominique Ingress later made a remark at the French Academy in Rome that “Gounod might have competed successfully for a Prix de Rome in fine arts.” His mother had been his piano teacher, and he had a clear and sweet voice. However, his musical fire was decidedly stoked by frequent visits to the Théâtre-Italien. In 1831 he heard Rossini’s “Otello,” and “went nearly wild with impatience and delight. I remember I could not eat for excitement… Oh what a night, what rapture; the voices, the orchestra; I was literally beside myself.” Hearing Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” in 1835, he wrote, “Mozart is already so utterly perfect from a musical and sensuous point of view, he added the deep and penetrating influence of the most absolute purity united to the most consummate beauty of expression. I sat in one long rapture from the beginning of the opera to its close.” And when he heard performances of Beethoven’s Pastoral and Choral symphonies, “his fate to become a musician was sealed.”

Charles Gounod: Fernand (Judith van Wanroij, soprano; Yu Shao, tenor; Nicolas Courjal, bass; Brussels Philharmonic; Hervé Niquet, cond.)

Charles Gounod, 1841

His mother finally relented, and arranged for Gounod to leave school one day each week for private lessons in harmony and counterpoint with Antoine Reicha. Gounod writes, “Reicha had the highest possible reputation as a theoretical musician. Besides being Professor of Composition at the Conservatoire, Reicha received private pupils in his own home… As samples of my boyish talent, I brought him a few sheets of manuscript music—ballads, preludes, scraps of valses, and so forth. Looking over them, Reicha said to my mother, “This child already knows a good deal of what I shall have to teach him, but he is unconscious of the knowledge he possesses.” Gounod was admitted to the Conservatoire de Paris in 1836 and studied compositions with Fromental Halévy, Henri Berton, Jean Lesueur and Ferdinando Paer, and piano with Pierre Zimmerman. A scholar writes, “The group represented an eclectic mix of compositional styles in 1830s Paris and each instructor passed away before Gounod had studied with him for 18 months. None proved to have a lasting influence on Gounod’s style and aesthetics, although he undoubtedly derived some of his admiration for Gluck from Le Sueur.” During his time at the Conservatoire he did meet Hector Berlioz, and he later wrote, “Berlioz and his music were among the greatest emotional influences of my youth.” Gounod competed for the Prix de Rome for the first time in 1837 at the tender age of 19 and won second prize. After a failed attempt the next year, he finally earned the Grand Prix in 1839 with the cantata “Fernand.” Gounod had surpassed his father, as François had taken the second prize in the Prix de Rome for painting in 1783.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Bach/Gounod: “Ave Maria”