Kurt Masur, 1968

For well over three decades, Kurt Masur was one of the world’s most celebrated conductors, having established an international reputation as “a sensitive and innovative interpreter of the Classical and Romantic repertoire, specifically Mendelssohn, Brahms and Tchaikovsky.” He was also known as the most prominent musician from communist East Germany. Masur never joined the Communist Party, and he was a thorn in the side of communist leadership. Masur declined repeated offers to leave East Germany, and instead became actively involved in the cause for freedom. In 1989, growing anti-government protests shook the city of Leipzig, and Masur publically criticized the violence by riot police against the demonstrators. On 9 October 1989, he read a public appeal for freedom of discussion in the socialist state. His appeal is widely regarded as helping convince Leipzig police to disregard orders from Berlin and allowed the protests to continue. “In the same century that saw two world wars, I was witness to a peaceful revolution,” he told reporters. The Berlin Wall fell in 1990 and led to the reunification of Germany, with Masur mentioned as a possible candidate for the German presidency. He declined, “I am a musician, not a politician,” he said. “I was only one among many people who overcame their fear.”

Kurt Masur and the Gewandhaus Orchestra: Brahms’ Symphony No. 2

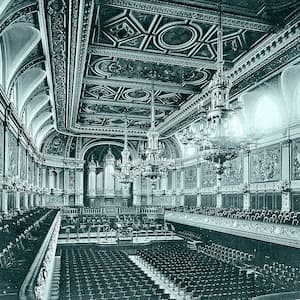

Interior of the Gewandhaus, 1886

Kurt Masur was born on 18 July 1927 in the city of Brieg, Silesia, now Brzeg, Poland. His father was an electrician, and he was destined to follow in his father’s footsteps. However, it became clear early on that his true passion and happiness lay in music. He taught himself to play the piano as a young child, and initially studied piano and cello at the Landesmusikschule in Breslau. Once he returned from conscription to the Second World War, he entered the University of Music and Theatre in Leipzig and studied composition and piano. However, Masur quickly specialized in conducting, “despite suffering from a nervous stutter.” He discontinued his studies in order to take up the position of répétiteur and staff conductor at the Halle Landestheater in 1948 and was subsequently first Kapellmeister at the city theatres of Erfurt and Leipzig, and conductor of the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra and the Komische Oper of East Berlin. In 1970 Masur received the crowing appointment of his early career: music director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, a position he would hold for 26 years.

Kurt Masur and the Gewandhaus Orchestra: Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazade (excerpt)

Kurt Masur laying the foundation stone of the current Gewandhaus

In the early 1970s, Leipzig was the industrial center of the communist run German Democratic Republic. The city’s main concert hall, the fabled Gewandhaus had been completely destroyed during the Second World War, and it had not been rebuilt nor restored. During his first year of tenure in Leipzig, the Gewandhausorchester was housed in a convention hall near the city’s zoological garden. Masur recalled, “When the music was quieter you could hear the lions roar…we were on the verge of embarrassing ourselves.”

Modern Gewandhaus, 1981

Masur made it his mission for his orchestra to be taken seriously, and he wrote to Erich Honecker, the leader of the GDR’s ruling Socialist Party. Masur campaigned for a new concert hall and recognizing the cultural and symbolic importance of the Leipzig Orchestra, the GDR leader authorized the construction of a new venue. The “Neue Gewandhaus” was opened in commemoration of the 200th anniversary of the orchestra taking up residence in the original Gewandhaus, on 9 October 1981. While in Leipzig Masur was credited with restoring a vanished glory to that ensemble and city’s musical life, “and made recordings of Beethoven (including a complete cycle of the symphonies), Mendelssohn, Bruckner, and Brahms, praised for their clarity, unforced expressiveness, and warm, cultivated sonorities.”

Kurt Masur and NYPO: Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3

Kurt Masur and his family, 1981

Despite the political challenges, Masur was allowed to take his orchestra on international tours, culminating in a performance at Carnegie Hall in 1974. The visit turned out to be prophetic as Masur was named the music director of the New York Philharmonic in 1991. As in Leipzig, Masur was charged with rebuilding the orchestra from the ground up. The ensemble, once considered one of the premiere American orchestras, “had devolved into a lackluster group: critically skewered, internally contentious and lacking clear artistic vision.” A critic wrote, “Before Mr. Masur arrived, the Philharmonic’s reputation was justly at a low point. Audiences were disenchanted. The players had long been unhappy; recording engagements were hard to come by, and radio broadcasts were nonexistent. Symphonic music was becoming less important to the culture of New York. The orchestra’s status had so fallen that the director’s post was rejected by major maestros.” A former concertmaster explained in 2012, “He was just so demanding and intense, and by the sheer intensity of his personality, it sorts of transformed most of us.” Masur’s tenure with the New York Philharmonic represents “one of its golden eras, in which music-making was infused with commitment and devotion, with the belief in the power of music to bring humanity closer together.” Masur once famously said, “If every school would hire two more music teachers, we would need two fewer police officers on the streets.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Kurt Masur and NYPO: Prokofiev, Strauß, and Bernstein