Sviatoslav Richter

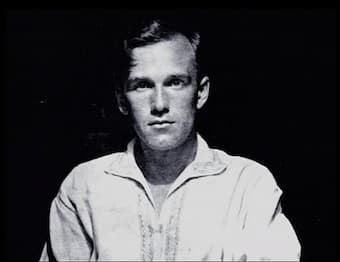

He was described as “a pianist with a technique that conquered almost every obstacle, a sound that commanded the colors of the rainbow and an intellect and imagination that permitted an authoritative grasp of possibly the largest repertory in pianistic history.” His teacher Heinrich Neuhaus recalled, “he treated each composition like a vast landscape, which he surveyed from great height with the vision of an eagle, taking in the whole and all the details at the same time. He played like no one I had ever heard, and there was nothing I could teach him.” We are talking of course about Sviatoslav Teofilovich Richter (1915-1997), who is widely regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time. He was born on 20 March in the northwestern Ukrainian town of Zhytomyr, then part of the Volhynian Governorate of the Russian Empire. His father was a pianist, organist and composer born to German expatriates, who had studied at the Vienna Conservatory. His mother, Anna Pavlovna Richter (née Moskaleva), came from a noble Russian landowning family, and at one point she studied under her future husband.

Franz Schubert: Fantasy in C Major, Op. 15, D. 760, “Wandererfantasie” (Sviatoslav Richter, piano)

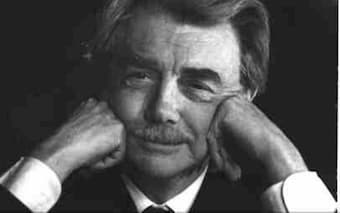

Heinrich Neuhaus, 1962

His father was teaching at the conservatory in Odessa, and the family primarily spoke German and French at home. When both father and son contracted typhus, the young boy was sent to live with his aunt Tarmar. He was greatly influenced by his creative aunt and showed a strong interest in both music and painting from an early age. It has been suggested, “If he had not been a great pianist, he would have made an excellent artist.” In addition, Richter developed a burning passion for literature and from the age of ten he read voraciously. He also developed a life-long interest in theatre and cinema, and he loved to take long walks, covering up to 30 miles a day. Richter was reunited with his parents in Odessa in 1921, but by that time his father was forced to resign his appointment to make room for the new Soviet professors. Although Richter did receive sporadic instruction from his father, he was essentially self-taught and free to develop his own piano technique. It is said “the boy had phenomenal sight-reading skills, playing full operatic scores at a glance.”

Sviatoslav Richter Plays Ravel’s Miroirs

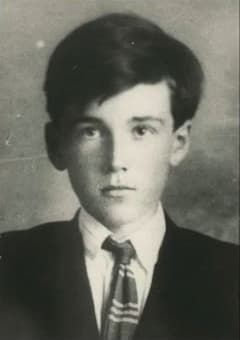

Richter as a young boy

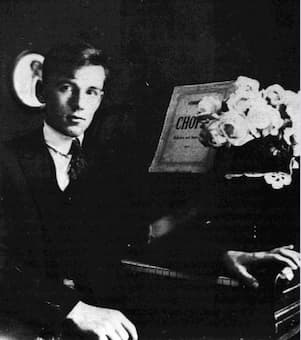

Richter never considered himself a prodigy, and as he recalled later, “was fiercely drawn to the theatre. When I turned 15, I started to accompany concerts, I played clubs, I started making some money, and once I earned a sack of potatoes. I worked for three years in the Palace of Marines, and they then took me to the opera. And the opera raised me.” He made his solo début playing Chopin at the age of 19, and in the following year became an accompanist at the Odessa Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre. When Richter saw Heinrich Neuhaus give a number of master classes in Odessa, he decided to audition with Chopin’s Ballade No. 4 in 1937. Neuhaus immediately considered Richter “a musician of genius,” and the young pianist moved into his teacher’s house and entered the Moscow Conservatory in 1937. Richter refused to study other subjects or take examinations and was expelled on three occasions but always reinstated at Neuhaus’ insistence. Richter made his official début on 26 November 1940, in the Small Hall of the Moscow Conservatory, playing works by Russian composers, including the first performance of Prokofiev‘s Sixth Sonata.

Sviatoslav Richter Plays Prokofiev’s 2nd Sonata

Neuhaus explained, when Richter “learned a new composition, he would work eight to ten hours non-stop at the piano, spending an eternity over a single page.” Apparently, Richter was the genius student Neuhaus had been waiting for all his life, while he readily acknowledged that he taught Richter “almost nothing.” Apparently, Richter also tried his hands at composition and even played some of his works for Neuhaus. However, he quickly gave up composition because, as he explained, “the best way I can put it is that I see no point in adding to all the bad music in the world.” With his parent’s marriage falling apart, Richter’s father came under suspicion by authorities. During one of Stalin’s purges his father was arrested and later charged as guilty of espionage. He was executed on 6 October 1941. Richter gave his first public recital in Moscow in July 1942, and he did play for the troops during the war.

Neuhaus explained, when Richter “learned a new composition, he would work eight to ten hours non-stop at the piano, spending an eternity over a single page.” Apparently, Richter was the genius student Neuhaus had been waiting for all his life, while he readily acknowledged that he taught Richter “almost nothing.” Apparently, Richter also tried his hands at composition and even played some of his works for Neuhaus. However, he quickly gave up composition because, as he explained, “the best way I can put it is that I see no point in adding to all the bad music in the world.” With his parent’s marriage falling apart, Richter’s father came under suspicion by authorities. During one of Stalin’s purges his father was arrested and later charged as guilty of espionage. He was executed on 6 October 1941. Richter gave his first public recital in Moscow in July 1942, and he did play for the troops during the war.

Johannes Brahms: Piano Quintet in F Minor, Op. 34 (Sviatoslav Richter, piano; Borodin Quartet)

He was frequently asked why he didn’t play some of the landmark works of piano literature. Richter replied, “When I have heard something played perfectly, I could not possibly take it up. I heard Neuhaus play Beethoven‘s Emperor and after that, I could have nothing to add. The same thing happened when I heard my classmate Gilels play Prokofiev’s Third Sonata. I loved that sonata, but after Gilels I had nothing more to say.” Richter made some of his best recording for the USSR State record company from 1948 and later for the Melodiya label. He performed across the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe as travel to the west was still restricted. However, by the 1960s he had become so famous that Soviet authorities could no longer contain him, and he caused a sensation playing five recitals at Carnegie Hall. Richter had no interest in America, “except for its art museums, its orchestras and its cocktails.” Richter was an intensely private person and was usually quiet and withdrawn, refusing to give interviews. In his performances he demanded that the focus be on the music performed, “rather than on extraneous and irrelevant matters such as performer’s grimaces and gestures.” As he famously remarked,

He was frequently asked why he didn’t play some of the landmark works of piano literature. Richter replied, “When I have heard something played perfectly, I could not possibly take it up. I heard Neuhaus play Beethoven‘s Emperor and after that, I could have nothing to add. The same thing happened when I heard my classmate Gilels play Prokofiev’s Third Sonata. I loved that sonata, but after Gilels I had nothing more to say.” Richter made some of his best recording for the USSR State record company from 1948 and later for the Melodiya label. He performed across the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe as travel to the west was still restricted. However, by the 1960s he had become so famous that Soviet authorities could no longer contain him, and he caused a sensation playing five recitals at Carnegie Hall. Richter had no interest in America, “except for its art museums, its orchestras and its cocktails.” Richter was an intensely private person and was usually quiet and withdrawn, refusing to give interviews. In his performances he demanded that the focus be on the music performed, “rather than on extraneous and irrelevant matters such as performer’s grimaces and gestures.” As he famously remarked,

“We are living in an age of voyeurs, and nothing is more fatal for music.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Sviatoslav Richter: Beethoven Recital, Moscow 1976

I love Beethoven’s music and Richter has reinforced my love for my uncle Ludwig’s music. Thank you for your wonderful life’s work. What a wonderful time I am having!