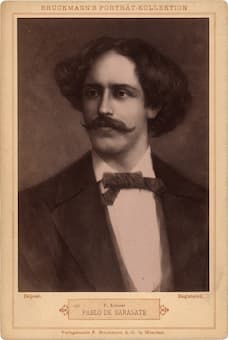

Pablo de Sarasate

The Hungarian violinist and teacher Carl Flesch writes in his Memoirs, “for all who played the violin during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Pablo de Sarasate was a magical name, and even more: he stood for aesthetic moderation, euphony, and technical perfection—and slightly superficial emotionality. With awe, as if he was a supernatural phenomenon from a wonderland forever inaccessible to us, we boys looked up to the small, black-eyes Spaniard with the well-trimmed, coal-black mustache and equally black, curly, over-carefully arranged hair.” Essentially, Flesch considered Sarasate a completely new type of violinist and the ideal embodiment of the salon virtuoso. As a scholar writes, “Sarasate’s playing was distinguished by sweetness and purity of tone, produced with a frictionless bow-stroke and colored by a shallow, fast vibrato. His technique was assured, his intonation was precise, especially in high positions, his use of portamento was varied and frequent, and his whole manner of playing was so effortless as to appear casual.”

Pablo de Sarasate Plays Zigeunerweisen, Op. 20 (excerpts)

© Friedric Bruckmann/Archivio Storico Ricordi

According to contemporaries, Sarasate considered his bowing first and foremost a means of producing the kind of tone which he regarded as ideal, “and which was of a pleasant and elegant smoothness, free from any extraneous noises, but at the same time not intensive and a little indifferent emotionally.” Carl Flesch provides the following analysis; “I was able to study his bowing technique from a distance of two yards above him, where I sat in a small gallery in the Rumanian Queen’s salon. I found that his stroke held constantly and firmly to the exact middle between the extreme regions of the bridge and the fingerboard, and hardly ever approached the bridge, where, as we know, a characteristic oboe-like intensity can be achieved. Sarasate’s effect on his audiences depended, in the first place, on the complete lack of friction in his tone production.” Sarasate’s supposed emotional indifference did cloud critical reviews. As a French critic wrote, “Spain is a beautiful but indifferent woman… And this general, indolent, indifference is especially fatal to musicians.” And in 1874 a London critic wrote, “Senor Sarasate did not excite any special sensation. Sarasate has an agreeable, but somewhat thin tone, and executes with neatness.”

Pablo de Sarasate: Spanish Dances Op. 21 (excerpts) (Louis Persinger, piano; Ruggiero Ricci, violin)

Although he made Paris his home, Sarasate initially struggled to establish himself in France as a performer. As such, he decided to seek his fame and fortune abroad. He embarked on a tour of North and South America that would last the better part of two years. As he writes, “I must succeed; I must achieve the goals which I have set myself, namely artistic success and monetary wealth… Prepare to shower me with affection in Paris when I do; that’s what I ask; that’s what I will need.” Sarasate was mightily impressed by the enormous Steinway Hall in New York, but he did not really warm to New York City. He writes, “New York is a miserable city, as are its people. Everyone lives only for business—anything else is just a hobby. The average American is the most sullen and unpleasant person that one can meet—not the kind of person one would wish to associate with.”

Although he made Paris his home, Sarasate initially struggled to establish himself in France as a performer. As such, he decided to seek his fame and fortune abroad. He embarked on a tour of North and South America that would last the better part of two years. As he writes, “I must succeed; I must achieve the goals which I have set myself, namely artistic success and monetary wealth… Prepare to shower me with affection in Paris when I do; that’s what I ask; that’s what I will need.” Sarasate was mightily impressed by the enormous Steinway Hall in New York, but he did not really warm to New York City. He writes, “New York is a miserable city, as are its people. Everyone lives only for business—anything else is just a hobby. The average American is the most sullen and unpleasant person that one can meet—not the kind of person one would wish to associate with.”

Pablo de Sarasate: Introduction and Tarantella, Op. 43 (Adele Anthony, violin; Akira Eguchi, piano)

Extensive travel aside, Sarasate never felt really at home except in Paris or in his native town of Pamplona. In February 1900, Pamplona declared him a “favorite son” of the city. However, an article in a Madrid newspaper, commenting on forthcoming concerts in Spain, attacked Sarasate for “his lack of patriotism and declared that vanity alone brought him back yearly to Pamplona, where he enjoyed being worshiped as a demigod.” For many years, Sarasate spent a month or six weeks at Biarritz following the end of the “Fiesta” in Pamplona. He bought himself a seaside villa at Biarritz in December 1901, which he duly named Villa Navarra. Sarasate died in Biarritz, France, on 20 September 1908, from chronic bronchitis. He bestowed his 1724 Stradivari to the Musée de la Musique, and the Real Conservatorio Superior de Música, Madrid, now owns his “Boissier” Stradivari. Sarasate was one of the few 19th-century virtuosos who lived into the gramophone era, and his 1904 recordings offer tantalizing evidence of his performance prowess.

Extensive travel aside, Sarasate never felt really at home except in Paris or in his native town of Pamplona. In February 1900, Pamplona declared him a “favorite son” of the city. However, an article in a Madrid newspaper, commenting on forthcoming concerts in Spain, attacked Sarasate for “his lack of patriotism and declared that vanity alone brought him back yearly to Pamplona, where he enjoyed being worshiped as a demigod.” For many years, Sarasate spent a month or six weeks at Biarritz following the end of the “Fiesta” in Pamplona. He bought himself a seaside villa at Biarritz in December 1901, which he duly named Villa Navarra. Sarasate died in Biarritz, France, on 20 September 1908, from chronic bronchitis. He bestowed his 1724 Stradivari to the Musée de la Musique, and the Real Conservatorio Superior de Música, Madrid, now owns his “Boissier” Stradivari. Sarasate was one of the few 19th-century virtuosos who lived into the gramophone era, and his 1904 recordings offer tantalizing evidence of his performance prowess.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Pablo de Sarasate: “Carmen Fantasy”