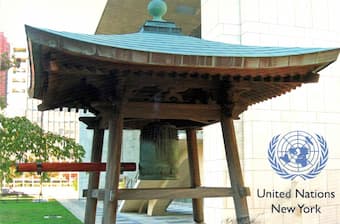

The International Day of Peace was established in 1981 by the United Nations General Assembly. It is dedicated to world peace, and specifically to the absence of war and violence, “such as might be occasioned by a temporary ceasefire in a combat zone for humanitarian aid access.” On 21 September the United Nations Peace Bell is rung at the UN Headquarter in New York City. That bell was cast from coins donated by children, and it was a gift from the United Nations Association of Japan, as “a reminder of the human cost of war.”

The International Day of Peace was established in 1981 by the United Nations General Assembly. It is dedicated to world peace, and specifically to the absence of war and violence, “such as might be occasioned by a temporary ceasefire in a combat zone for humanitarian aid access.” On 21 September the United Nations Peace Bell is rung at the UN Headquarter in New York City. That bell was cast from coins donated by children, and it was a gift from the United Nations Association of Japan, as “a reminder of the human cost of war.”

United Nations Peace Bell

The inscription reads, “Long live absolute world peace.” This day has taken on a special theme and importance in 2021, as we are still battling with the COVID-19 pandemic. “We are inspired to think creatively and collectively about how to help everyone recover better, how to build resilience, and how to transform our world into one that is more equal, more just, equitable, inclusive, sustainable, and healthier.”

Shiro Fukai: Prayer for Peace (Noriko Sasaki, soprano; Yuko Anazawa, alto; Jun Suzuki, tenor; Katsunori Kono, baritone; Commemoration Chorus of Documentation Centre for Modern Japanese Music; Orchestra Nipponica; Honna Tetsuji, cond.)

Shiro Fukai

An official United Nations document asserts, “This pandemic has been accompanied by a surge in stigma, discrimination, and hatred. The virus attacks all without caring about where we are from or what we believe in. Confronting this common enemy of humankind, we must be reminded that we are not each other’s enemy. To be able to recover from the devastation of the pandemic, we must make peace with one another.

Andrzej Panufnik

And we must make peace with nature. Despite the travel restrictions and economic shutdowns, climate change is not on pause.” The United Nations family invites us all to join the effort in recovering for a more equitable and peaceful world. “Celebrate peace by standing up against acts of hate online and offline, and by spreading compassion, kindness, and hope in the face of the pandemic, and as we recover.”

Andrzej Panufnik: A Procession for Peace (Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Warsaw; Łukasz Borowicz, cond.)

Augusta Read Thomas

In 2015 the music critic Edward Reichel wrote, “Augusta Read Thomas has secured for herself a permanent place in the pantheon of American composers of the 20th and 21st centuries. She is without question one of the best and most important composers that this country has today. Her music has substance and depth and a sense of purpose.” Thomas thinks of herself as a poet-composer, sculpting music the way poets create, refine, and polish their poems. Yet, the outcome of her compositions is often unpredictable for the composer. “I stay absolutely flexile,” she writes, “everything is malleable… I slide, skate, swivel, and spin with my materials… In the end, I feel as if the piece wrote me.” A professor of composition, and one of the most active composers in the world, Thomas is also deeply committed to her community. Scored for wordless soprano and string quartet, Plea for Peace acts as a single, “seamless block beginning in near-immobility, with the voice animating the instruments as the music embarks on its slow, implacable progress. The work’s ultimate peak is as vociferous as it is inevitable. But, as the ending winds back to the opening stillness, there’s no sense of fulfillment or arrival. The listener, along with the music, is left awaiting an answer to this impassioned plea.”

Augusta Read Thomas: Plea for Peace (version for voice and string quartet) (Jessica Aszodi, soprano; Yuan-Qing Yu, violin; Ni Mei, violin; WeiJing Wang, viola; Ken Olsen, cello)

Mieczysław Weinberg

Mieczysław Weinberg (1919-1996) has been described as “one of the most individual and compelling musical voices of the twentieth century.” Although his music enjoyed some success in the 1960s and 70s, Weinberg was never a party figure. As such, he was never able to attract much support from the Soviet government. He only composed two works commemorating official occasions, and that includes the festive poem “The Banners of Peace” written in 1985. The work bears a dedication to the 27th Congress of the Soviet Communist Party, and is partly based on revolutionary songs already sounded in Shostakovich’s 11th Symphony. “The work seems well removed from the propagandistic,” and sounds a mournful yet optimistic tone. Rhetorical interjections from the brass do unsettle the soulful sounding strings, “but its most notable aspect is its evident lack of irony.”

Mieczysław Weinberg: The Banners of Peace, Op. 143 (St. Petersburg State Symphony Orchestra; Vladimir Lande, cond.)

Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) wrote his “Peace on Earth” in 1907. He took the words from an 1886 poem by the Swiss writer Conrad Ferdinand Meyer. In the first verse we find a depiction of the Nativity, and the second tells of bloodshed and imploring angels. The peace captioned in the title gradually emerges in the third and fourth verses. Schoenberg eventually became disillusioned with the concept of “universal harmony among men and his choral evocation, one of the last pieces of his early tonal period, would later elicit a somber remembrance from the composer.” Schoenberg wrote that peace on earth is “merely an illusion, one created when I still believed such a unity was possible.” When we celebrate the International Day of Peace on 21 September, we have no option but to believe that it is still possible.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Arnold Schoenberg: Peace on Earth, Op. 13 (Simon Joly Chorale; Robert Craft, cond.)