Sir Arthur Sullivan

On Friday 23 November 1900, The Times published the following obituary. “The death of Sir Arthur Sullivan, which we announce this morning with great regret, not only deprives England of the man who for many years has been her most conspicuous composer, but will afflict all who care for music with a keen sense of personal loss… No one who had any ear for music at all could fail to appreciate the grace and fancy which always marked Sir Arthur Sullivan’s work… What captivated the majority and set Sullivan in popular esteem far above all the other English composers of his day was the tunefulness of his music, that quality in it by which, without ever descending to mere trickery or to commonplace catchiness, it found its way to the ear at once and was immediately recognized as a joyous contribution to the gaiety of life.”

Charles Lyall: Drawing of Arthur Sullivan, lazily conducting

The obituary seemingly focuses on Sullivan’s 14 collaborations with the dramatist W. S. Gilbert, which included such hits as H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance and The Mikado. Sullivan’s compositions for the music theatre enjoyed broad and enduring international success and they are still frequently performed today. Without doubt, they served as models for future generations of West End and Broadway composers. Less known is the fact that Sullivan also wrote a number of serious concerts works that are gradually being rediscovered today.

Arthur Sullivan: Symphony in E Major, “Irish” (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Richard Hickox, cond.)

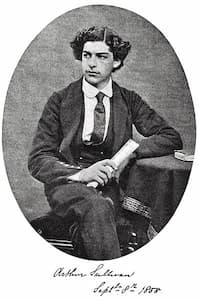

Young Arthur Sullivan at RAM

Sullivan had been suffering from ill health throughout his life. Returning to London from Switzerland, he was nursing an upper respiratory infection. His chest and lungs became affected, but his doctor believed that Sullivan was making satisfactory progress towards recover. As newspapers reported, “quite suddenly and altogether unexpectedly, alarming symptoms were observed by the nurse. A messenger was at once dispatched for the doctor, but before that gentleman could arrive the end came at 9 o’clock on 22 November 1900. The immediate cause of death is said to have been failure of the heart’s action.

Sullivan at age 18 in Leipzig

Sir Arthur was aware that he was suffering from heart trouble.” The first part of the burial service took place in the Chapel Royal, St. James’s, the place where Sullivan had started his career as a choirboy. The Chapel was lavishly decorated, “and the Queen was represented by Sir Walter Parratt, her Majesty’s Master of Music, who was the bearer of a wreath of laurels.” The congregation included members from all classes of society, representing music, the arts, and politics. The funeral procession headed to St. Paul’s Cathedral, and the funeral marches of Chopin, Mendelssohn, and Beethoven were performed on the Cathedral organ. “Sir Arthur Sullivan’s remains were laid to rest on the north side of the crypt.” A memorial concert took place at Crystal Palace on December 8 and featured vocal, orchestral, and choral selections from the composer’s work.

Arthur Sullivan: 5 Sacred Partsongs (Kantos Chamber Choir; Ellie Slorach, cond.)

During the latter part of Sullivan’s life, the composer “suffered recurrent doubt as to whether he was wasting his time and talents on ephemeral works, and his state of mind was not helped by members of the British musical establishment who insisted that he was.” In fact, critics and academics quickly disparaged Sullivan’s status immediately following the composer’s death. While he was recognized for his contributions to the music theatre, Sullivan was openly accused of “prostituting his talents.” Fuller Maitland wrote, “The Offenbachs and Lecocqs, the Clays and the Celliers, did not degrade their genius, for they were incapable of higher things than they accomplished … But if the author of The Golden Legend, the music to The Tempest, Henry VIII and Macbeth cannot be classed with these, how can the composer of ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers’ and ‘The Absent-Minded Beggar’ claim a place in the hierarchy of music among the men who would face death rather than smirch their singing-robes for the sake of a fleeting popularity?” Ernest Walker wrote in his history of Music in England of 1907, that songs like “The Lost Chord,” and “The Sailor’s Grave” were “disgraceful rubbish,” and that Sullivan was “after all, the idle singer of an empty evening.”

During the latter part of Sullivan’s life, the composer “suffered recurrent doubt as to whether he was wasting his time and talents on ephemeral works, and his state of mind was not helped by members of the British musical establishment who insisted that he was.” In fact, critics and academics quickly disparaged Sullivan’s status immediately following the composer’s death. While he was recognized for his contributions to the music theatre, Sullivan was openly accused of “prostituting his talents.” Fuller Maitland wrote, “The Offenbachs and Lecocqs, the Clays and the Celliers, did not degrade their genius, for they were incapable of higher things than they accomplished … But if the author of The Golden Legend, the music to The Tempest, Henry VIII and Macbeth cannot be classed with these, how can the composer of ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers’ and ‘The Absent-Minded Beggar’ claim a place in the hierarchy of music among the men who would face death rather than smirch their singing-robes for the sake of a fleeting popularity?” Ernest Walker wrote in his history of Music in England of 1907, that songs like “The Lost Chord,” and “The Sailor’s Grave” were “disgraceful rubbish,” and that Sullivan was “after all, the idle singer of an empty evening.”

Arthur Sullivan: String Quartet in D minor (Yeomans String Quartet)

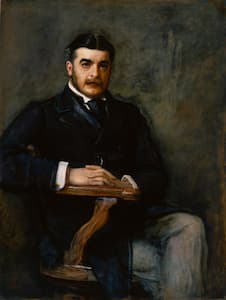

Arthur Sullivan, Chorister of the Chapel Royal,

circa 1855

Scholars have suggested that these “attacks may now be seen in the context of partisanship for the concept of a ‘British musical renaissance’ supposedly beginning with the generation after Sullivan, including Stanford, Parry and Mackenzie.” In the eyes of his critics, Sullivan should rightfully have been the leader of this musical renaissance. Sullivan showed supreme musical talent at an early age, and he was the first recipient of the Mendelssohn Scholarship, which offered free tuition for one year at the Royal Academy of Music. That scholarship was extended for a second and third year, which offered Sullivan the opportunity to study at the Leipzig Conservatory. Ignaz Moscheles became his personal mentor and one of his piano teachers, and Sullivan also took composition lessons with Julius Rietz. His graduation work at Leipzig, which he conducted on 6 April 1861, “was a suite of incidental music to The Tempest much along the lines of Mendelssohn’s to A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” Once Sullivan had returned to London, George Grove arranged for a performance of the Tempest music, and it was an immediate and extraordinary success. In fact, it was hailed “as possibly marking an epoch in English music.” As such, critics subsequently lamented “Sir Arthur Sullivan did not aim consistently at higher things, setting himself up to rival Offenbach and Lecocq instead of competing on a level of high seriousness with such musicians as Sir Hubert Parry and Professor Stanford. If he had followed this path, he might have enrolled his name among the great composers of all time.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Arthur Sullivan: The Tempest, Op. 1 “Suite” (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Richard Hickox, cond.)

I always say a Mass for Sir Arthur every year on the anniversary of his death. My late father loved his music and would always bring home a new G&S recording when I was a boy. I consider the Savoy Operas his pinnacle of talent. His orchestration for Princess Ida is technically superior to anything else he ever composed; especially the music for the cello in the same opera. I know this is going to sound strange, but I feel as if I knew him. He died in 1900 and I came 58 years later, so how can that be? I used to sing “Onward Christian Soldiers” in church occasionally. No composer who ever lived, with the possible exception of Mozart, ever wrote sparkling vocal Melodies.

I was educated at the Duke of York’s Royal Military School which rescued and educated Sir Arthur’s father Thomas, son of a soldier father absent for 5 years on campaign leaving his wife and children living in poverty. Thomas was trained in the (still existing) military band which formed the basis of his largely military musical career. In the 1960s the annual school show was a G&S. Albeit I accept that Arthur made his way thru’ church music, Chapel Royal onto Royal Academy of Music & Leipzig Conservatoire, I can only observe that by age 8, in his own admission, he could play something on the wind instruments of the band. This could only have been in his father’s bandroom at RMC Sandhurst. As the son of an army bandmaster myself I know that the musical diet of brass & woodwind, march and popular melody is prevalent in Sullivan’s output and so his militarily-inspired beginnings should not be overlooked. His father Thomas’s influence was more important than credited.