Concert Program on December 23, 1806

During his formative years in Bonn, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1828) took organ and keyboard lessons from Christian Gottlob Neefe. Concurrently, he received instructions on the violin and viola from the court musician Franz Georg Rovantini and from Franz Ries, Electoral-Court music director, respectively. His first teacher of the violin, however, had been his father. A highly doubtful but delightful anecdote tells that young Beethoven preferred to improvise on the violin rather than reading the notes from the score. Supposedly, his father reprimanded him with the words, “What silly trash are you scratching together now? You know I can’t bear that—scratch by note, otherwise your scratching won’t amount to much.” Although Beethoven was primarily focused on establishing his career as a piano virtuoso, he continued to take violin lessons from Wenzel Krumpholtz after his move to Vienna in 1792. Beethoven’s student Ferdinand Ries reports, “we still sometimes played the Krumpholtz sonatas with violin together. But that was really a dreadful music; for in his enthusiastic keenness, Beethoven did not hear when he wrongly fingered a passage.” Although Beethoven’s violin playing was far from proficient, he began to compose and publish various works for strings, including his first violin sonatas. The three Violin Sonatas Op. 12 are dedicated to the imperial court composer Antonio Salieri, who was Beethoven’s composition teacher at the time.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D Major, op. 61 – I. Allegro ma non troppo (Arabella Steinbacher, violin; Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra; Andris Nelsons, cond.)

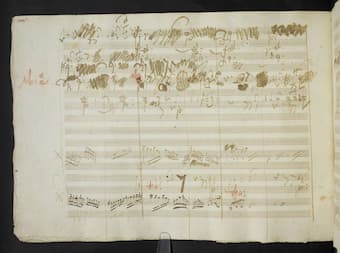

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto corrections

Beethoven had come to Vienna as a showcase pianist, and he was looking for ways to combine virtuosity with symphonic structure. The composer had first experimented with concerto structure at the age of 14, and his initial published works for piano and orchestra solidified his reputation. However, he also composed two Romances for Violin and Orchestra, a concerto for the unusual combination of piano, violin and cello and his singular Violin Concerto, Op. 61. Working on a commission from the violinist and conductor Franz Clement (1780-1842), who would also be the featured soloist in the benefit concert in his own honor, Beethoven completed the work within a couple of weeks in the latter part of 1806. Beethoven had met Clement in 1794 when he attended a performance by the 14-year-old prodigy in Vienna. Beethoven was suitably impressed and prophesied that Clement “would reach the greatest goal possible to an artist here on earth” and implored him to “return soon so that I may hear your dear magnificent playing.” Clement did became the concertmaster at the Theater and der Wien, and Beethoven entrusted him to conduct the premiere of his Eroica symphony at a benefit concert on 7 April 1805. A critic described Clement’s unique prowess as a violinist in 1805. “His is not the marked, bold, strong playing, the moving, forceful Adagio, the powerful bow and tone which characterise the Rode-Viotti School; rather, his playing is indescribably delicate, neat and elegant; it has an extremely delightful tenderness and cleanness that undoubtedly secures him a place among the most perfect violinists. At the same time, he has a wholly individual lightness, which makes it seem as if he merely toys with the most incredible difficulties, and a sureness that never deserts him for a moment, even in the most daring passages.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D Major, op. 61 – II. Larghetto (Janine Jansen, violin; Bremen Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie; Paavo Järvi, cond.)

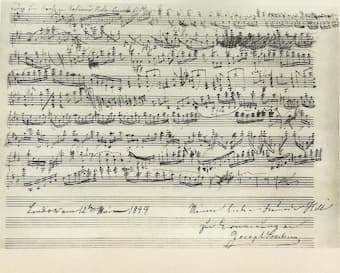

Joseph Joachim in London, 1844

Apparently, Clement was known for his extraordinary ability to play complex pieces from memory after only briefly viewing them. This particular ability must have come in really handy on 23 December 1806, as he featured as the soloist at the premiere of the Beethoven Violin Concerto. The composer had been working on the piece until shorty before the performance, and Clement basically played the concerto at sight and from memory. Another unusual feature of this premiere was the fact that the concerto was played in two halves. The first movement was given before the interval, and once the performance resumed, Clement entertained the crowd by “playing a sonata on one string or with the violin held upside-down.” After this display of lighthearted showmanship, the final two movements of the Beethoven concerto were given. The work was not well received and almost immediately disappeared. A critic wrote, “With regard to Beethoven’s concerto, the opinion of all connoisseurs is the same: while they acknowledge that it contains some fine things, they agree that the continuity often seems to be completely disrupted, and that the endless repetitions of a few commonplace passages could easily lead to weariness. It is being said that Beethoven ought to make better use of his admittedly great talents….”

Joseph Joachim’s cadenza to the Rondo of

Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, May 12, 1844

The concerto only gained a permanent place in the repertoire in 1844 when the twelve-year-old Joseph Joachim performed the work under Felix Mendelssohn’s direction in London. It has been suggested that Clement’s wonderful cantabile even in the highest registers left a decided mark on the concerto. “The concerto’s considerable technical demands always serve the purpose of expression and the principles of symphonic design; brilliant virtuosity and violinistic acrobatics are secondary.” As it happens, the concerto was not dedicated to Clement but to Stephan von Breuning, an old friend from Bonn with whom Beethoven used to share violin lessons and living quarters in his student days.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Concerto in D Major, op. 61 “Rondo”