Niccolò Paganini

Niccolò Paganini gave the world a new kind of musician, the musical superstar with a devoted following. Everything he did in performance, including his love for black clothes, his carefully disheveled hair, and his over-the-top mannerisms, was deliberately planned to craft a “cult of personality and mystery to accompany his virtuoso playing.” And while a good many of today’s superstars trade on their charisma to smooth over the edges of basic incompetence, Paganini lived up to his own hype. “He never allowed anyone to hear him practice, and there seemed no limit to his facility on the violin, nothing too difficult or technically unconventional that he could not master.” Paganini was particularly known for his left-hand pizzicato notes, and a technique he called the “ricochet,” which involves the bouncing of the bow quickly across the strings. “Most dazzling of all, Paganini executed flawless runs of double-stop harmonics at lightning speed.” Sporting an extended arsenal of virtuoso pyrotechnics, the violin concerto became the perfect vehicle to demonstrate his supposedly “demonic” virtuosity. In addition, the central Adagio accorded the soloist the opportunity to demonstrate refined lyricism and tone. As a critic writes, “Paganini wanted to dazzle his audience, but he also wanted to move them.”

Niccolò Paganini: Violin Concerto No. 3 in E Major – I. Andante – Allegro marziale (Salvatore Accardo, violin; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Charles Dutoit, cond.)

Paganini composed his 3rd Violin Concert in E major in 1826, during a period of some personal difficulties. Paganini had been involved with a young singer by the name of Adriana Bianchi, who bore him a son named Achillino in 1825. By all accounts, Adriana Bianchi “was a troublesome partner, jealous and unpredictable in her behavior, while Paganini, twice her age, was increasingly subject to illness.” Forced to take a rest in Naples, he completed his 2nd Violin Concerto and wrote to a close friend on 12 December 1826. “I am now finishing orchestrating a third with a ‘Polacca.’ I would like to try these concertos out on my own countrymen before producing them in Vienna, London, and Paris.” Resuming his performance schedule, Paganini appeared in Rome, Florence, Perugia, and Leghorn, a tour only interrupted by the need to look after his son, who had broken his leg and needed constant attention. With continued illness plaguing his daily life, Paganini finally accepted an invitation from Prince Metternich to visit Vienna, and the new concerto was first performed at the Redoutensaal on 24th July, in one of the fourteen lucrative concerts Paganini gave in the city. Franz Schubert was in the audience, and he described Paganini’s playing as “the singing of an angel.”

Paganini composed his 3rd Violin Concert in E major in 1826, during a period of some personal difficulties. Paganini had been involved with a young singer by the name of Adriana Bianchi, who bore him a son named Achillino in 1825. By all accounts, Adriana Bianchi “was a troublesome partner, jealous and unpredictable in her behavior, while Paganini, twice her age, was increasingly subject to illness.” Forced to take a rest in Naples, he completed his 2nd Violin Concerto and wrote to a close friend on 12 December 1826. “I am now finishing orchestrating a third with a ‘Polacca.’ I would like to try these concertos out on my own countrymen before producing them in Vienna, London, and Paris.” Resuming his performance schedule, Paganini appeared in Rome, Florence, Perugia, and Leghorn, a tour only interrupted by the need to look after his son, who had broken his leg and needed constant attention. With continued illness plaguing his daily life, Paganini finally accepted an invitation from Prince Metternich to visit Vienna, and the new concerto was first performed at the Redoutensaal on 24th July, in one of the fourteen lucrative concerts Paganini gave in the city. Franz Schubert was in the audience, and he described Paganini’s playing as “the singing of an angel.”

Niccolò Paganini: Violin Concerto No. 3 in E Major – II. Adagio, cantabile spinato (Salvatore Accardo, violin; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Charles Dutoit, cond.)

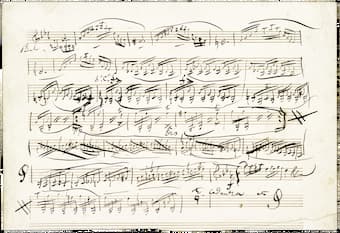

Paganini’s Cadenza for Violin

Paganini spent four months in the city of Vienna, and he actually transformed the town. Contemporary accounts report that shop windows displayed everything from gloves to pasta “a la Paganini,” and that walking sticks were embellished with his portrait. Mass hysteria continued to spread, and everyone wanted to hear Paganini play. Franz Schubert urged his friend Eduard von Bauernfeld to attend one of the concerts, even though the ticket price had risen astronomically to five guilders. Bauernfeld was mightily impressed and wrote, “We heard the infernal, heavenly violinist and were no less enchanted by his wonderful Adagio than we were highly astonished by his other devilish arts, and not a little humorous built by the unbelievable scratching feet of the demonic figure, one of which was on wires drawn, skinny, black doll.”

Anton Gräffer, who worked for the Viennese publisher Artaria, was astounded that “Paganini played and conducted from memory,” a performance practice unusual in Vienna at that time. He also reports that the famous Viennese violinist Joseph Mayseder “ended his concert career the day after Paganini played his first concert in Vienna.” According to the Beethoven student Ferdinand Ries, “Mayseder wrote in a letter that all violin players might as well hang their fiddles on the wall now that Paganini had come.” To be sure, Paganini had a remarkable effect on the audience as he simultaneously combined extraordinary technical virtuosity with the ability to move the listener’s feelings. Prior to his departure, the Emperor elevated Paganini to the rank of “Imperial and Royal Chamber Virtuoso,” and presented him with a golden casket. Paganini left Vienna with his pockets full of money, and he was ready to conquer all of Europe.

Anton Gräffer, who worked for the Viennese publisher Artaria, was astounded that “Paganini played and conducted from memory,” a performance practice unusual in Vienna at that time. He also reports that the famous Viennese violinist Joseph Mayseder “ended his concert career the day after Paganini played his first concert in Vienna.” According to the Beethoven student Ferdinand Ries, “Mayseder wrote in a letter that all violin players might as well hang their fiddles on the wall now that Paganini had come.” To be sure, Paganini had a remarkable effect on the audience as he simultaneously combined extraordinary technical virtuosity with the ability to move the listener’s feelings. Prior to his departure, the Emperor elevated Paganini to the rank of “Imperial and Royal Chamber Virtuoso,” and presented him with a golden casket. Paganini left Vienna with his pockets full of money, and he was ready to conquer all of Europe.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Niccolò Paganini: Violin Concerto No. 3 in E Major – III. Polacca: Andantino – Vivace (Salvatore Accardo, violin; London Philharmonic Orchestra; Charles Dutoit, cond.)