Gustav Holst

Gustav Holst’s reputation had been steadily growing during the years before World War I, and in 1917 “he composed the choral and orchestral Hymn of Jesus, perhaps the most characteristic and original work of his maturity.” His true breakthrough, however, took place in 1918 with the first performance of The Planets. This set of seven self-contained orchestral “mood pictures,” propelled the composer to international prominence. However, this sudden fame came with a hefty price tag. Holst had always wanted to be just a simple composer, but suddenly he was in great demand at various social functions and the press was haunting him for endless interviews and public appearances. Publishers kept asking for revisions of his earlier pieces, and he conducted numerous concerts of his works. Exhausted, Holst fell from the podium while conducting at the University of Reading in February of 1923. “Every artist ought to pray that he may not be a success,” he wrote. “If he is a failure he stands a good chance of concentrating upon the best work of which he is capable.”

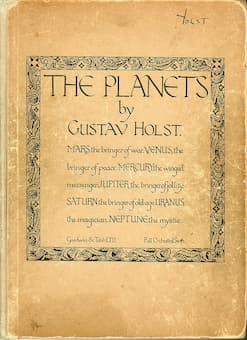

Gustav Holst: The Planets, Op. 32

Holst: The Planets (composer’s personal copy)

In 1927, the town of Cheltenham organized the first major festival devoted to Holst’s music. The City of Birmingham Orchestra gave two concerts with identical programs in Cheltenham Town Hall, and the composer gave a short speech during the ceremony. Holst “expressed his gratification and said that what he most appreciated in the honor which his native town was paying him was the blow it dealt at the prevalent fallacies that music was a foreign language and that all composers were dead.” On the heels of the Holst Festival, the New York Symphony Orchestra commissioned Holst to write an orchestral work. Egdon Heath premiered at Cheltenham in February 1928 with one critic writing, “Whereas the first choral symphony was stillborn, Egdon Heath can scarcely be said to have been born at all.” Holst also started work on his final opera The Wandering Scholar, a work completed in January 1930.

Gustav Holst: Egdon Heath (Homage to Hardy), Op. 47 (London Symphony Orchestra; André Previn, cond.)

Gustav Holst’s statue in Cheltenham

In January 1932, Holst sailed for the USA to take up the appointment as Horatio Lamb lecturer in composition at Harvard University. He taught, among others, Elliott Carter and conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Holst attended theatre performances in New York, but found life in New York incredibly hectic, especially the use of the telephone. As he once remarked, “New Yorkers rush to the phone as inveterate smokers do to cigarettes.” Halfway through this hectic visit to the United States, Holst was taken ill and rushed to hospital. He was diagnosed with suffering from a duodenal ulcer, and had lost four pints of blood. As he subsequently recounted to Ralph Vaughan Williams, “I felt I was sinking so low that I couldn’t go much further. And, as I have always expected, it was a lovely feeling… As soon as I reached the bottom, I had one clear, intense and calm feeling, that of overwhelming gratitude. And the four chief reasons for gratitude were music, the Cotswold, Ralph Vaughan Williams, and having known the impersonality of orchestral playing.” Scholars have suggested that this near-death experience “represented a release from decades of chronic overwork.”

Gustav Holst: Brook Green Suite (Royal Philharmonic Orchestra; Barry Wordsworth, cond.)

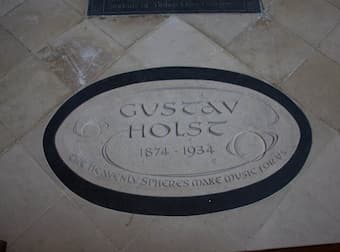

Holst memorial, Chichester Cathedral

Holst returned to England, and during the “last eighteen months of his life, in spite of having to live largely as an invalid, he composed some of his most individual works, including the Brook Green Suite and the Lyric Movement for viola and orchestra.” Holst was taken ill again in October 1933 and admitted to a clinic in December. Apparently, doctors advised that he had two choices, namely a major operation or to lead a restricted life as an invalid. Holst opted to undergo the operation, and on 23 May 1934 the duodenal ulcer was removed. The operation was declared a success, but it severely weakened his body. Gustav Holst “passed away quietly and peacefully” in London of heart failure on 25 May 1934, at the age of 59. His ashes were interred at Chichester Cathedral in Sussex, close to the memorial of Thomas Weelkes, his favourite Tudor composer. Bishop George Bell gave the memorial oration at the funeral, and Vaughan Williams conducted music by Holst and himself.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gustav Holst: Lyric Movement