Dmitry Shostakovich, 1950s © Deutsche Fotothek

Born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, on 25 September 1906, Dmitry Shostakovich was the second of three children of Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich and Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina. His father was studying physics and mathematics at St Petersburg University, and subsequently worked as an engineer in the Bureau of Weights and Measures. His mother studied languages and piano in Siberia, and eventually became a student of Aleksandra Rozanova at the St Petersburg Conservatory. Young Dmitry grew up in privileged surroundings following the Revolution. “The family had use of two cars and a dacha, owned a Diderichs piano, and employed a German tutor, servants and a nanny.”

The New Babylon

However, when the composer fell from official grace, the need to earn money dictated the nature of his compositions. As such he undertook a succession of commissions from the film industry. Already as a student he had played piano in silent cinemas, and over the next decades he wrote almost forty film scores. Shostakovich wrote his first film score for the 1929 silent historical drama “The New Babylon,” written and directed by

Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg. The film tells the story of the 1871 Paris Commune, and follows the tragic fate of two lovers separated by the barricades. Although the film flopped badly, Shostakovich was asked by the directors to write music of their next film as well.

Dmitry Shostakovich: New Babylon, Op. 18 (Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra; James Judd, cond.)

The Gadfly

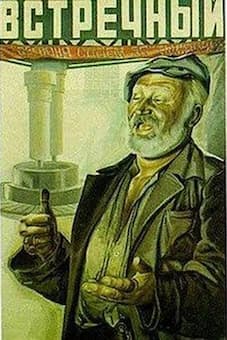

Composing for the stage and the screen was a lucrative undertaking. The New Babylon netted Shostakovich the tidy sum of 2,000 rubles. Directed by Sergey Yutkevich and Fridrikh Ermler, “The Counterplan” was a 1932 Soviet drama film with a rather primitive propaganda message. It centers on a Leningrad factory constructing a powerful turbine under the enthusiastic leadership of committed Party Secretary Vasya. He is secretly in love with Katya, his friend Pavel’s wife, but will be disappointed. Construction of the turbine is interrupted by the careless work of the old drunk Babchenko and errors in the drawings, which the bourgeois wrecker Skvortsov had spotted but deliberately ignored. Nevertheless, the factory successfully delivers the turbine and Babchenko learns to forego vodka and use modern methods, and wants to join the Party. The delighted boss raises a toast. Supporting this romantic tale of the heroic efforts of young workers, Shostakovich composed one of his brightest and most popular scores. Full of dancing rhythms and memorable tunes, the soundtrack was described favorable by critics around the world.

Dmitry Shostakovich: Counterplan, Op. 33 (Excerpts) (Rheinland-Pfalz State Philharmonic Orchestra; Mark Fitz-Gerald, cond.)

The Counterplan

Following Stalin’s death in 1953, Shostakovich experienced some personal tragedies and financial hardship. His wife Nina died in December 1954, and his parents-in-law-suffered from serious illnesses. When his mother died in November 1955, Shostakovich almost stopped composing completely, and he fell on financially hard times. When illness forced Aram Khachaturian to resign from scoring the film “The Gadfly,” Shostakovich stepped in. Shostakovich would have been familiar with the novel by Ethel Voynich set during the 19th-century Italian struggle against Austrian rule. The plot centers on the life of the protagonist Arthur Burton, and his tragic relationship with his love Gemma. It is a story of faith, disillusionment, revolution, romance, and heroism and it resonated with Soviet concerns in terms of the excoriation of religion, and the binding together of disparate states. Shostakovich produced one of his most accessible and popular scores, using the lush descriptions of Alpine scenery in a series of atmospheric and colorful character pieces. One of his greatest hits is the “Romance” accompanying the sensitive Arthur in the library of his mentor Cardinal Montanelli. Giovanni Bolla speaks to a “Young Italy” meeting, and Arthur is jealous that his girlfriend Gemma is enraptured by Bolla’s oratory.

Dmitry Shostakovich: The Gadfly, Op. 97 (Excerpts) (Yuri Torchinsky, violin; Peter Dixon, cello; BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Vassily Sinaisky, cond.)

The Man with a Gun

Released in 1938, The Man with a Gun deals with the recent history of the Soviet state. “All came into being as parts of the overall plan of mythologizing the October Revolution and the first post-revolutionary years, of re-interpreting the history of that epoch from the point of view of full-grown and firmly established Stalinism.” This film originated in a theater play by Nikolai Pogodin, with the action taking place in the days of the Bolshevik uprising of 1917. The Revolution is seen through the eyes of an ignorant and easy-going peasant who, as a soldier, gets caught up in the proceedings. Unsurprisingly, Lenin and Stalin are among its dramatis personae. Shostakovich had been announced the forthcoming “Lenin Symphony” but after his music to “The Man with a Gun” was enthusiastically received, this symphony was never written. Shostakovich claimed to have studied revolutionary songs to help him in his work. When several Lenin films were re-released in the 1960s, all scenes featuring Stalin, alongside Shostakovich’s music, were removed.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Dmitry Shostakovich: The Man with a Gun, Op. 53 (BBC Philharmonic Orchestra; Vassily Sinaisky, cond.)