Once Giuseppe Tartini returned to Padua from his two-year stay in Prague, he quickly set up his famous violin school “La scuola delle nazioni” in 1728. By that time he already had an international reputation, which brought students from all over Europe to his school.

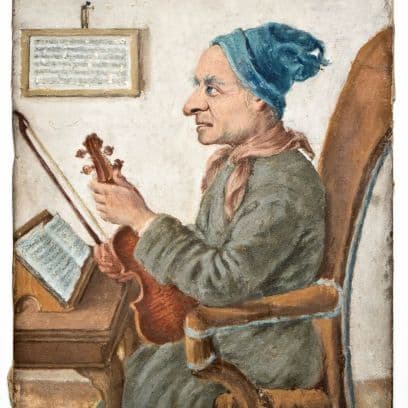

The Tartini School

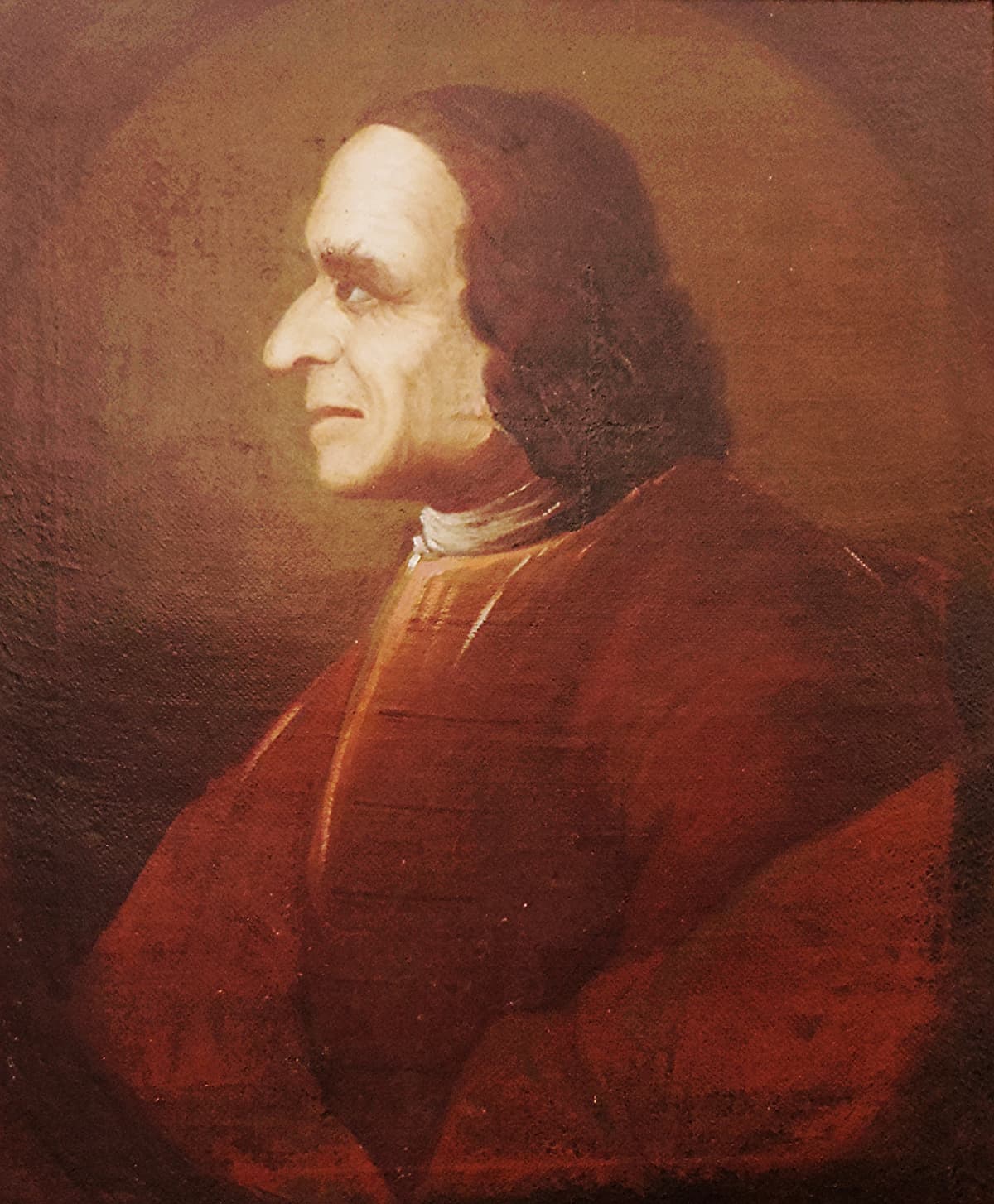

Giuseppe Tartini

Nicknamed the “Master of Nations,” Tartini not only taught violin technique but also focused on composition. A course of study lasted normally two years, and the “Tartini School” was the first instrumental school of such fame. A number of his students achieved reputations of their own, as both players and composers, but countless others are only known by their names or a few compositions. But we do know that Tartini instructed girls from the Venetian conservatories, among them Maddalena Lombardini Sirmen (1745-1818). Of noble birth but growing up in abject poverty, Lombardini was trained at San Lazzaro dei Mendicanti, one of the four great hospices in Venice. We also know that Lombardini was occasionally given permission to leave and study with Giuseppe Tartini, and he apparently paid her tuition for musical lessons in Padua and at the orphanage.

Giuseppe Tartini: Violin Concerto in F Major, D. 66 (Federico Guglielmo, violin; L’Arte dell’Arco; Federico Guglielmo, cond.)

Tartini’s Most Famous Letter

Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua Italy. Cloister of the Blessed Luke. Monument to Giuseppe Tartini

After receiving her maestra license, and marrying the renowned violinist Ludovico Sirmen, Maddalena “established a reputation as one of the finest and most famous violinists and composers,” and a contemporary wrote, “She won the hearts of all the people of Turin with her playing. I wrote to old Tartini last Saturday telling him the good news. It will make him all the happier, since this student of his plays his violin compositions with such perfection that it is obvious she is his descendant.” Lombardini-Sirmen is also the recipient of the most famous letter that Tartini ever wrote. Because of this letter, dated 5 March 1760, we know what was actually taught in the “Tartini School.” Tartini writes, “I shall begin the instructions you wish from me, by letter; and if I should not explain myself with sufficient clarity, I entreat you to tell me your doubts and difficulties, in writing, which I shall not fail to remove in a future letter.” And Tartini’s first sentence encapsulates his principle teaching aims. “Your study should at present be confined to the use and power of the bow, in order to make yourself entirely mistress in the execution and expression of whatever can be played or sung within the compass and ability of your instrument.”

Giuseppe Tartini: Violin Sonata No. 50 in G Major, B.G12 (Črtomir Šiškovič, violin; Luca Ferrini, harpsichord)

Tartini’s Teaching

Giuseppe Tartini

Right from the beginning, Tartini is primarily concerned with complete control of the bow. And he does make the distinction between “cantabile” and “suonabile.” The first implies the use of a legato technique, directly modeled on vocal style, in order to create clearly defined musical phrases; the second, typical of the instrumental idiom, implies a more detached performance style. “These two ways of playing are clearly distinct, almost antithetic.” Having outlined his method of producing a tone, Tartini moves one to the advanced use of the bow. “The second precaution,” he writes, “is that you first play with the point of the bow, and when that becomes easy to you, that you use that part of it which is between the point and the middle; and above all, you must remember in these studies to begin the allegros or flights sometimes with an up-bow and sometimes with a down-bow, carefully avoiding the habit of constantly practicing one way.

Giuseppe Tartini: Violin Sonata No. 17 in D Major, B.D2 (Črtomir Šiškovič, violin)

Tartini Monument

Tartini continues, “I now pass to the third essential part of a good performer on the violin, which is making a good shake, and I would have you practice it slow, moderately fast, and quick; that is, with the two notes succeeding each other in these three degrees of adagio, andante, and presto, and in practice, you have great occasion for these different kinds of shakes, for the same shake will not serve with equal propriety for a slow movement as for a quick one… You must attentively and assiduously persevere in the practice of this embellishment.” It was Tartini’s aim to more fully characterize a melody through embellishments, and the entire section devoted to embellishments in Leopold Mozart‘s Violinschule is simply a translation of the first part of Tartini’s treatise on the same subject. In the last decades of his life, Tartini concentrated his efforts on matters of music theory. A number of treatises and shorter theoretical texts emerged from 1754, which discussed music theory on a mathematical basis; these texts were hotly discussed amongst his peers in Italy and abroad. As a biographer wrote, “throughout his life, Tartini was harassed by requests for financial help from his family back in Pirano, which obliged him to devote his last years more than ever to teaching.” Tartini died in Padua on 26 February 1770, and he is buried in St. Catherine’s church.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Giuseppe Tartini: Violin Sonata in G minor “Devil’s Trill”