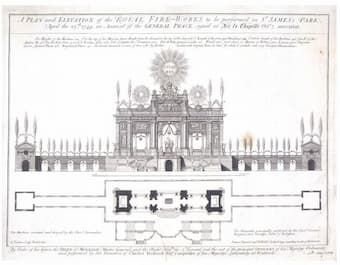

To celebrate the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ultimately ended the War of Austrian Succession, King George II of Great Britain hosted a gargantuan festival on 27 April 1749. Citizens from all corners of the kingdom arrived in London to witness a lavish fireworks display that erupted from a massive machine. That machine was a large wooden pavilion painted to resemble stone, 410 feet long and 114 feet high, constructed by the Chevalier Nicolas Servandoni, architect of St. Sulpice and stage designer for the Paris Opera. The pyrotechnic structure was “adorned with Frets, Gilding, Lustres, Artificial Flowers, Inscriptions, Statues, Allegorical Pictures and the like,” and it took five months to build. To add to the vast expense, roughly 10,000 rockets were installed and operated by a team of Italian explosive experts. To accompany this explosive spectacle, the King commissioned George Frideric Handel, then 64 years old and at the height of his popularity, to compose some background music.

To celebrate the treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which ultimately ended the War of Austrian Succession, King George II of Great Britain hosted a gargantuan festival on 27 April 1749. Citizens from all corners of the kingdom arrived in London to witness a lavish fireworks display that erupted from a massive machine. That machine was a large wooden pavilion painted to resemble stone, 410 feet long and 114 feet high, constructed by the Chevalier Nicolas Servandoni, architect of St. Sulpice and stage designer for the Paris Opera. The pyrotechnic structure was “adorned with Frets, Gilding, Lustres, Artificial Flowers, Inscriptions, Statues, Allegorical Pictures and the like,” and it took five months to build. To add to the vast expense, roughly 10,000 rockets were installed and operated by a team of Italian explosive experts. To accompany this explosive spectacle, the King commissioned George Frideric Handel, then 64 years old and at the height of his popularity, to compose some background music.

George Frideric Handel: Royal Fireworks Music “Overture”

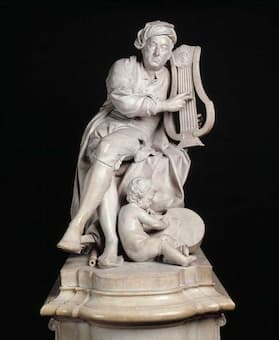

George Frideric Handel

Handel quickly set to work and designed music for a traditional orchestra of strings, winds and percussion. The King, who was personally supervising the preparations, however, wasn’t particularly happy and “insisted instead on a very large ensemble of only war-like instruments.” The Duke of Montagu, Master-General of the Ordinance in charge of all British artillery and fortification, was the officer responsible for the Royal Fireworks, and he acted as the messenger between King George and Handel. Handel wasn’t the most even-tempered individual, and when he got the message that the King was “hoping for no fiddles,” he changed the scoring to include more violins while reducing the number of wind instruments. The argument, apparently, was only settled at the very last moment with Handel bowing to the King’s wishes.

George Frideric Handel: Royal Fireworks Music – II. “Bourrée” (English Baroque Soloists; John Eliot Gardiner, cond.)

Fireworks machine

Handel was also not keen on having a full rehearsal of the music in Vauxhall Gardens and not in Greek Park. Once again, the composer had to accede to the wishes of the King, and on April 21, 1749, an estimated 100 musicians rehearsed the new composition in the Gardens for an audience of 12,000. Admission was half a crown, and the crowd so large that it stopped traffic on London Bridge—the only vehicular route to the area south of the river—for three hours. Despite the grand confusion, Handel’s music was an unqualified success. On 25 April, for the official service of thanksgiving at St. James’s Palace, Handel composed the anthem “How Beautiful Are the Feet,” with music borrowed from the Messiah.

George Frideric Handel: Royal Fireworks Music “La Paix”

‘Handel’, by Louis François Roubiliac, 1738

Finally, on 27 April the official premiere of the Music for the Royal Fireworks took place in Green Park. Initially, Handel’s “Grand Overture of warlike instrument” was played for the crowd, “while the King and his entourage toured Servandoni’s machine.” During an earlier rehearsal for the firing of 101 brass canons, a soldier had sadly lost his arm, and things would get a lot worse. During the main event, the firing of the canons alternated with music, and the fireworks started at 8:30. The weather was rainy causing many misfires, while inside the machine, English and Italian technicians argued about safety. A stray rocket set a woman’s clothes on fire, and another burned two soldiers and blinded a third. To make matters worse, the spectacular neoclassical pavilion that had served both as concert stage and launch-point for the fireworks caught on fire during the display. As strong winds fanned the flames, the crowd fled in panic. “The fire was brought under control, but, in his frustration, the Chevalier Servandoni drew his sword and had to be disarmed and arrested.”

George Frideric Handel: Royal Fireworks Music “La Réjouissance”

The British politician Horace Walpole wrote, “the display by no means answered the expense, the length of preparation, and the expectation that had been raised. Although the machine was worth seeing, the fireworks themselves were a mixed affair and lighted so slowly that scarce anybody had patience to wait for the finishing.” Apparently, a good deal of the fireworks was still unused when the display was stopped at midnight. Newspapers had a field day, but everybody agreed that Handel’s music had been a complete success. The exact instrumentation for the premier performance remains uncertain. We know that the orchestration was settled at nine trumpets, nine horns, 24 oboes, 12 bassoons, three pairs of timpani, and an unspecified number of side drums. However, if we are to believe that “100 musicians” had been on stage, Handel must have augmented the “war instruments” with at least 40 string players after all. And we do know that Handel re-scored the suite for full orchestra for a performance on 27 May at the Foundling Hospital.

The British politician Horace Walpole wrote, “the display by no means answered the expense, the length of preparation, and the expectation that had been raised. Although the machine was worth seeing, the fireworks themselves were a mixed affair and lighted so slowly that scarce anybody had patience to wait for the finishing.” Apparently, a good deal of the fireworks was still unused when the display was stopped at midnight. Newspapers had a field day, but everybody agreed that Handel’s music had been a complete success. The exact instrumentation for the premier performance remains uncertain. We know that the orchestration was settled at nine trumpets, nine horns, 24 oboes, 12 bassoons, three pairs of timpani, and an unspecified number of side drums. However, if we are to believe that “100 musicians” had been on stage, Handel must have augmented the “war instruments” with at least 40 string players after all. And we do know that Handel re-scored the suite for full orchestra for a performance on 27 May at the Foundling Hospital.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

George Frideric Handel: Royal Fireworks Music “Menuets 1 and 2”