Gabriel Fauré

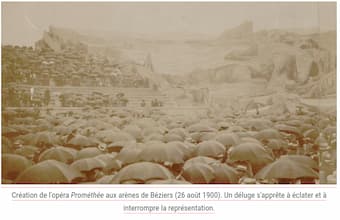

On 27 August 1900 a massive number of performers assembled at Arènes de Béziers to premiere the tragédie lyrique, essentially the grand cantata Prométhée by Gabriel Fauré. The performing cast, numbering almost 800 participants including two wind bands and 15 harps. As it happened, an audience of well over 10,000 spectators watched this massive musical event, partly based on the opening of the Greek tragedy of Prometheus Bound. This outdoor spectacular almost did not come to pass as a terrific thunderstorm virtually destroyed the set on 25 August, only two days before the premier. As has been reported, “the lightning struck in the exact spot where Prométhée was to steal the fire, and Pierre Lalo in Le Temps drew the obvious parallel.” It took almost superhuman effort and around-the-clock-construction to get the set ready in time for the premier. The performance was a triumphant success, and Fauré’s music was being especially praised. Saint-Saëns, who had urged Fauré to write large-scale works, told the composer, “With your Prométhée you have astounded your colleagues, including me.”

Gabriel Fauré: Prométhée (Excerpt)

Premiere of Fauré’s Prométhée at Arènes de Béziers

Fauré was well pleased, noting to his wife “that the wind dispersed the sound a bit, but the performance was as good as it could possibly be.” Critics, however found fault with the spoken parts for Prométhée and Pandore, and considered them “feeble and overlong.” In addition, the plot of the opera, describing Prométhée stealing the fire from heavens and the Gods revenge in the form of Pandore’s box filled with human suffering, was declared “patchy and for the most part mediocre.” The work was modeled on classical Greek tragedies with spoken dialogue and musical interludes, and Jean Lorrain and Ferdinand Hérold had adopted the text from the opening of the Greek tragedy

Gabriel Fauré: Prométhée (Excerpt)

Fauré composed the music for his most important theatrical work in less than six months between February and July 1900. He reports to his wife from Montpellier in March “that my hosts were bewildered by the boldness of my harmonies, but to me they seemed almost platitudinous; it’s all a question of degree!” As the librettists were slow delivering their texts, Fauré had still not composed much music by the end of March. Once the work was completed, however, Saint-Saëns wrote to the publisher Jacques Durand, “All my fears as to whether Fauré would match up to the breadth and nobility of the character of the subject had been put to rest. I know of no one else capable of achieving lines of such dimension or such simplicity within this severely contoured work, myself included.” And he subsequently added that Fauré’s score “had that invaluable quality of being the only music suitable for the work.”

Fauré composed the music for his most important theatrical work in less than six months between February and July 1900. He reports to his wife from Montpellier in March “that my hosts were bewildered by the boldness of my harmonies, but to me they seemed almost platitudinous; it’s all a question of degree!” As the librettists were slow delivering their texts, Fauré had still not composed much music by the end of March. Once the work was completed, however, Saint-Saëns wrote to the publisher Jacques Durand, “All my fears as to whether Fauré would match up to the breadth and nobility of the character of the subject had been put to rest. I know of no one else capable of achieving lines of such dimension or such simplicity within this severely contoured work, myself included.” And he subsequently added that Fauré’s score “had that invaluable quality of being the only music suitable for the work.”

Gabriel Fauré: Prométhée, “Le Cortège de Pandore”

Gabriel Fauré and Prométhée

According to a biographer, Prométhée “marks a turning point in Fauré’s career as it looks forward to the final period. Dialogue and singing alternate, the latter being reserved for the chorus and the Gods. Prométhée and Pandore have spoken roles, though they are represented by musical motifs. Fauré was apprehensive about Wagnerian comparisons, but the finest pages are pure Fauré. The composer “applied his undoubted talents for powerful dramatic music on a larger scale than before, and succeeding for the most part in providing a varied and effective score for a difficult work, which suffers both from the long passages of dialogue which put the mortals, who form the crux of the action, at a disadvantage, and from its alfresco festival conception.” Fauré recreated Prométhée the following summer, with the assistance of Saint-Saëns and Roger Ducasse. However, indoor revivals, as that of 5 December 1907 at the Ancien Hippodrome in Paris for the flood victims of the Hèrault met with little artistic success. As a critic wrote, “this hybrid work has, however, succeeded rather better in the concert version with a reduced arrangement for symphony orchestra.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Gabriel Fauré: Prométhée (Excerpt)