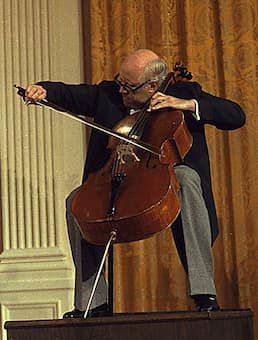

Mstislav Rostropovich

Mstislav Rostropovich has been called the greatest cellist of the second half of the 20th century, and one of the greatest of all time. Armed with impeccable technique, his playing produced a unique richness of tone as he famously exploited the tonal resources of the instrument. In addition, Rostropovich was famous for inspiring and commissioning new works, “which enlarged the cello repertoire more than any cellist before or since.” In fact, he inspired and premiered well over 100 compositions. However, besides being an incomparable instrumentalist and all-round musician, Rostropovich also became a moral force speaking out against tyranny and injustice. He was born in Baku, the capital of the Azerbaijan SSR on 27 March 1927. He liked to tell the story that he wasn’t wanted. “My mother understood too late that she was pregnant; she cried all over the house. My parents decided that I would have to be aborted because she already had a little child. It was a joint decision. So my mother started to fight against me, but as you see, I won this war.”

Rostropovich Plays Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major, BWV 1007

“Slava,” as he would famously become known, was born into a musical dynasty that had moved from Orenburg, the birthplace of his mother. His father Leopold was a renowned cellist and teacher who had studied with Tchaikovsky‘s friend Aleksandr Wierzbilowicz, and later with Pablo Casals. His grandfather was a composer of Polish noble descent, and his mother Sofiya, daughter of musicians of Russian lineage. Her elder sister Nadezhda married the cellist Semyon Kozolupov, who was thus Rostropovich’s uncle by marriage. And let’s not forget that his sister Veronika was a violinist, and that his maternal grandmother was head of a music school. Slava grew up in Baku and he taught himself to play the piano at the age of four, undoubtedly with some instruction from his mother. He is even said to have produced his first attempts at composition at that time. He started studying the cello with his father at the age of eight, and he was found to have perfect pitch. In his early teens, the family was evacuated to the western Russian city of Orenburg, where Slava “gained his first experience performing with a small group of musicians.

“Slava,” as he would famously become known, was born into a musical dynasty that had moved from Orenburg, the birthplace of his mother. His father Leopold was a renowned cellist and teacher who had studied with Tchaikovsky‘s friend Aleksandr Wierzbilowicz, and later with Pablo Casals. His grandfather was a composer of Polish noble descent, and his mother Sofiya, daughter of musicians of Russian lineage. Her elder sister Nadezhda married the cellist Semyon Kozolupov, who was thus Rostropovich’s uncle by marriage. And let’s not forget that his sister Veronika was a violinist, and that his maternal grandmother was head of a music school. Slava grew up in Baku and he taught himself to play the piano at the age of four, undoubtedly with some instruction from his mother. He is even said to have produced his first attempts at composition at that time. He started studying the cello with his father at the age of eight, and he was found to have perfect pitch. In his early teens, the family was evacuated to the western Russian city of Orenburg, where Slava “gained his first experience performing with a small group of musicians.

Rostropovich/Richter Play Beethoven’s Cello Sonata No. 5 in D major, Op. 102

Rostropovich as Chief conductor of

U.S. National Symphony Orchestra

By the mid-1930s, the family moved to Moscow and Rostropovich first appeared in public as a soloist at the age of 13, performing the Saint-Saëns A-minor Concerto in 1942. He entered the Moscow Conservatory in 1943 to study cello with his uncle Kozolupov, piano with Nikolai Kuvshinnikov, and composition with Vissarion Shebalin. He was also able to join Shostakovich’s orchestration class. Rostropovich once said, “Shostakovich was the most important man in my life, after my father.” When he was a student, Shostakovich was dismissed from his professorships in Leningrad and Moscow in response to the 10 February 1948 decree condemning the composer for “formalist perversions and antidemocratic tendencies.” In protest, Rostropovich quit the conservatory and he also smuggle to the West the manuscript of his teacher’s Symphony No. 13, “emphasizing Soviet indifference to the Babi Yar massacre.” Around the same time, Rostropovich won competitions in Moscow and subsequently Prague and Budapest, and at the age of 23 he was awarded the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, the Stalin Prize.

Rostropovich Plays Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1

Rostropovich in 1978

By the time he obtained his PhD in 1948, Slava was recognized as one of the Soviet Union’s most brilliant instrumentalists. In addition, Rostropovich had an intense working relationship with Soviet composers of the era. In 1949 Sergei Prokofiev wrote his Cello Sonata in C, Op. 119, for the 22-year-old Rostropovich, who gave the first performance in 1950, with Sviatoslav Richter. Prokofiev also dedicated his Symphony-Concerto to him. Dmitri Shostakovich wrote both his first and second cello concertos for Rostropovich, who also gave their first performances. But his relationship with the Soviet State was anything but smooth. In an open, and predictably unpublished letter to Pravda, the state-run newspaper he wrote, “Explain to me, please, why in our literature and art so often people absolutely incompetent in this field have the final word? Every man must have the right fearlessly to think independently and express his opinion about what he knows, what he has personally thought about and experienced, and not merely to express with slightly different variations the opinions which has been inculcated in him.”

Rostropovich Plays Britten’s Cello Suite No. 2

Plaque on building where Azerbaijani and Rostropovich lived in Baku

In the end, Rostropovich was ready to sacrifice everything, and when he supported Alexander Solzhenitsin in the late 1960s, “he was restricted to touring inside the USSR, before being exiled with his wife in 1974. His name was expunged from scores dedicated to him, and his wife was removed from the official history of the Bolshoi Theatre, and in 1978 they were stripped of their Soviet citizenship. However, they did outlive the Soviet system, and his Soviet citizenship was restored in January 1990. Rostropovich left a legacy that is both artistic and political. For one, he leaves an extended recorded legacy as a cellist, and from the late 1960s, he developed a second career as a conductor, notably with the National Symphony Orchestra, Washington, and as a guest conductor with the London Philharmonic and London Symphony orchestras. In addition, he stood up for his beliefs and fought for art without borders, freedom of speech, and democratic values. He is remembered as an artistic genius, a champion of human rights, and a consummate ambassador for music.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Rostropovich Plays Prokofiev’s Sinfonia Concertante (Excerpt)