Brigitte Engerer with her teacher Stanislav Neuhaus

Stanislav Neuhaus, son of the legendary pianist and pedagogue Heinrich Neuhaus, would likely have won the Chopin Prize in 1949. However, the Soviet regime did not allow him to make the trip to Warsaw, and thus he shared the pedagogical workload of his father’s studio and also taught at the Moscow Conservatory. He has been described as “one of the most tragic figures in Russian music.” Although he was a great pianist, he always felt himself to be in the shadow of his famous father, and his adoptive father, the great poet-novelist Boris Pasternak. He died from alcoholism at the age of 53, and he described his student and lover Brigitte Engerer as “one of the most brilliant pianists of her generation. Her playing is characterized by its artistry and romantic spirit, its depth, the perfection of her technique, and her innate ability to reach the listener.” Engerer remembers, “he always tried to make other people happy, but he could never make himself happy.” In addition, she credits Neuhaus for “opening her eyes and ears to the intersections of visual art, poetry, history, and music.”

Brigitte Engerer Plays Saint-Saëns’ Piano Concerto No. 2, “Andante Sostenuto”

Engerer had left France to study in Moscow at the age of seventeen, and she was in love with Stanislav from the start. However, she did not become romantically involved until almost five years later, after she had won a prize in the 1974 Tchaikovsky Competition. Of Maltese descent, Brigitte Engerer was born on 27 October 1952 in Tunis, then the French Protectorate of Tunisia. She started piano lessons at the age of three, and played her first public concert aged six. Her family moved to France when she was 11, and Brigitte entered the Paris Conservatoire to study with Lucette Descaves. By 1968, she was unanimously awarded a premier prix, and the following year she won the Concours International Marguerite Long-Jacques Thibaud. She was awarded a one-year scholarship to further her studies at the Moscow Conservatory in the class of Stanislav Neuhaus, “but she loved Stanislav and Russia so much that she stayed for almost 10 years.”

Franz Liszt: Schubert – Schwanengesang, S560/R245: No. 7. Standchen, “Leise flehen meine Lieder” (Brigitte Engerer, piano)

Critics described her playing, reflecting the warmth and generosity of her personality, as “a mixture of the French school with its playfulness and lucidity, and the full-bodied Russian tradition.” “I need the transparency of the French piano” she says, “and, more important, the rationality of French philosophy. But I needed some of the Russian craziness in my playing.” True to form, she made notable recordings of Russian music, including works of Mussorgsky, Rachmaninoff, and Tchaikovsky. She also recorded Ravel’s complete works for violin and piano, and her unforced technique and poetic approach “also made her an outstanding interpreter of Schumann.” According to her agent, “a part of her decidedly became Russian.” Engerer certainly spent some difficult and tumultuous years in Russia, but then “I lost the man I loved, I lost a country that I had learned to love and I lost the language I had been speaking.” As such, Engerer made the decision to move back to France.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Les saisons (The Seasons), Op. 37a (Brigitte Engerer, piano)

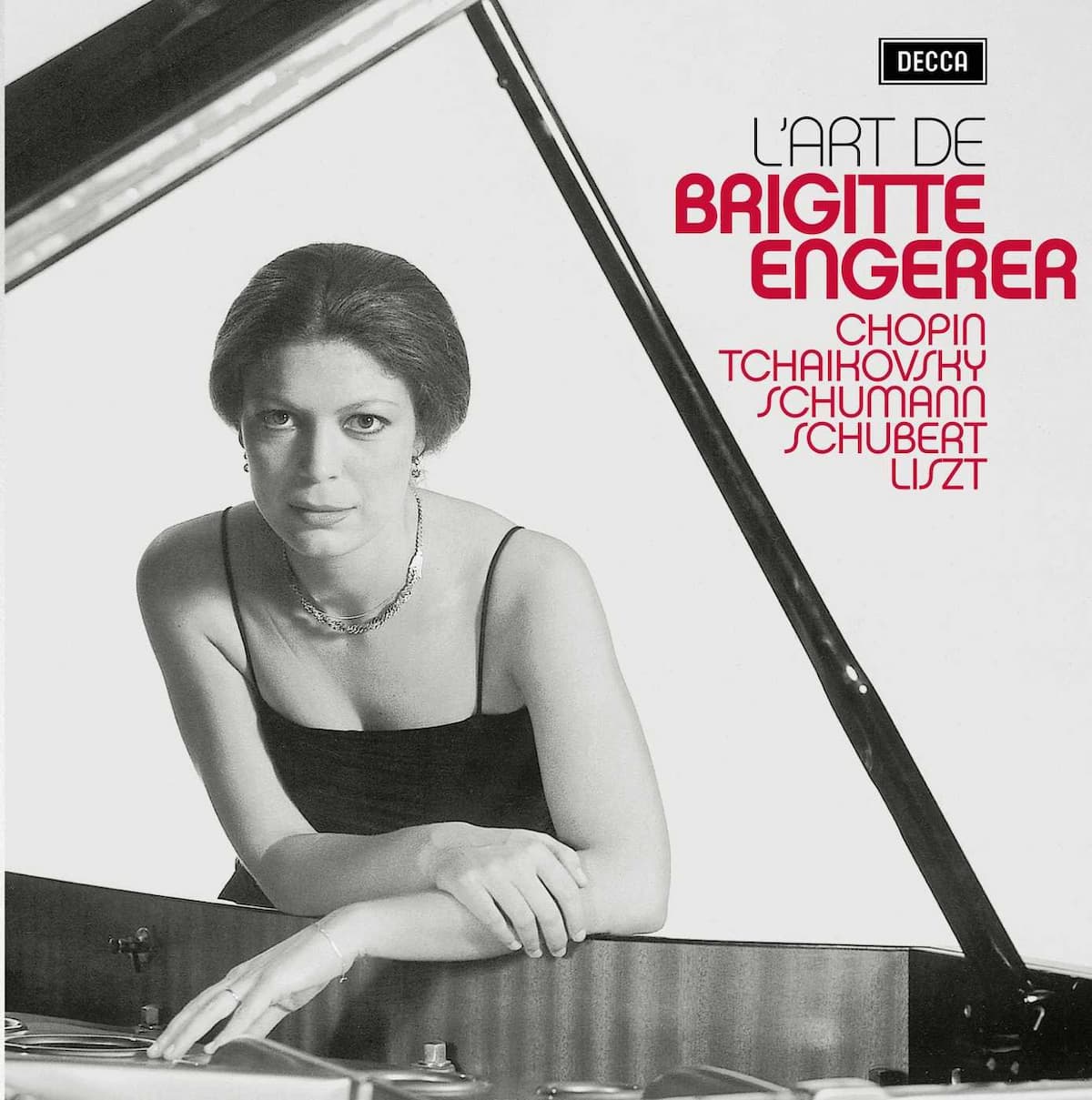

Brigitte Engerer

A critic wrote, “Engerer really came back to Paris as a Russian pianist. She played with a lot of spontaneity, it was temperamental playing, but it was not overly showy. Like her personality, it was warm and vivacious and very direct.” Moving back to Paris was not easy. “After 10 years, I felt as ignorant as a Russian immigrant,” she says. “In Russia, all concerts were arranged by the state-run concert agency. In the West, musicians had to make it on their own, and I had to learn how to be aggressive.” Engerer sent a tape of her playing to Herbert von Karajan, and he asked her to audition. “I played some Mozart, some Schumann, some Chopin, and some Rachmaninoff,” she says. “He said, ‘I love your left hand.’ The next thing I knew I was in the office of his assistant being booked to play with the Berlin Philharmonic. I thought ‘This is not real life; this is a Hollywood movie.’”

Just three years later she gave her New York debut, performing the Tchaikovsky Concerto for an enthusiastic audience and critics. Engerer was well aware that she would not become famous, because “I am no longer—how do you say it—fresh meat. Sometimes, I don’t know even what to make of myself. I’m French, but I feel Russian. I’m a Roman Catholic, but I feel Jewish. Then sometimes I feel like I’m a dinosaur because there are so few of us left who love music. But, then, I think that when we few dinosaurs find each other, we make each other very happy.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Brigitte Engerer Plays Chopin’s Nocturne