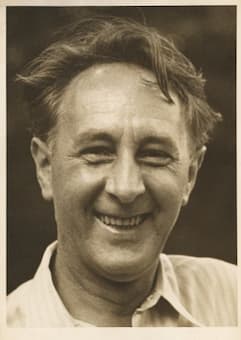

Bohuslav Martinů, 1943

Escaping Nazi oppression, Bohuslav Martinů found refuge in the United States. Struggling financially and eternally homesick, Martinů started to set folk song texts that became a symbolic connection to his beloved homeland. Dejected dreamlike vision of peace and the longing for his country contrasted sharply with the imperfections of the real world. Sensing his own mortality, Martinů returned to his European roots in 1953. Classified as an emigrant traitor by the communist government in his native Czechoslovakia, Martinů resettled in the south of France. The Czechoslovakian government had not only banned the man from returning to his home, it had virtually banned his music as well. In the compositions of Martinů’s last years, “we find the composer attempting through his music a vicarious homecoming.” In a letter to his old friend, the writer and poet Miroslav Bureš, Martinů suggested that the premiere of the Cantata Otvírání studánek (The Opening of the Wells) might take place in their hometown of Polička. “That way,” he wrote, “at least part of me will be able to return home.”

Bohuslav Martinů: The Opening of the Wells

Bohuslav and Charlotte Martinů

In 1941, Martinů penned a brief autobiography, consisting of sixteen handwritten pages that he wrote at breathtaking speed and in the third person. As the composer explained, “From his earliest compositions, Martinů emphasizes clarity of themes and melody, and his goal is to produce exact expressions based on absolute musical elements. He does not search for effects, but immediacy. He does not strive for abandon, but constraint and discipline, choosing means that are often simple and even primitive… He avoids any kind of exaggerated emotional outbursts and pathos, and he always contains the composition within absolute musical possibilities that function according to inner musical relationships.” Martinů continues, “His melody, rhythm, and sonic character is derived directly from Czech character and forms a direct link to Smetana and Dvořák.” Martinů’s musical legacy consists of almost 400 compositions, ranging from choral works and operas to symphonies and a great deal of chamber music. “The artist is always searching for the meaning of life, his own and that of mankind, searching for the truth,” he once wrote. “A system of uncertainty has entered our daily life. The pressures of mechanization and uniformity to which it is subject calls for protest and the artist has only one means of expressing this, by music.”

Bohuslav Martinů: Symphony No. 6 “Fantaisies symphoniques”

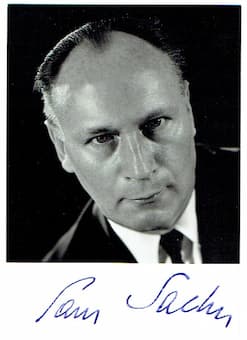

Paul Sacher

There has been some heated scholarly discussion as to whether or not Martinů suffered from Asperger syndrome. It was Frank James Rybka, who personally met Martinů a number of times, who suggested that the composer suffered from this kind of autism spectrum disorder. According to Rybka, “Martinů was quiet, introverted, and emotionally stolid when meeting persons he did not know well. He typically answered questions very slowly, even when conversing in his native Czech.” Based on the composer’s personality and on interviews of people who knew him, evidence of his having an autism spectrum disorder was compiled and evaluated, using the established criteria found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disease (DSM-IV). A well-known autism neuroscientist concurred that there was good evidence that the composer had an autistic spectrum disorder, most likely Asperger syndrome. It was concluded that the condition “facilitated his extraordinary memory for music, and his ability to compose prolifically and skillfully, but it also left him unable to promote or showcase his music in public.” While we may never know with complete certainty, these findings have been questioned by a number of musical and medical experts.

Bohuslav Martinů: Mikeš from the Mountains (Eva Mullerova, soprano; Jakub Turek, tenor; Prague Mixed Choir; Silvie Hessová, violin; Radek Křižanovský, violin; Pavel Ciprys, viola; Karel Košárek, piano; Jiří Petrdlík, cond.)

Martinů’s grave in Polička, Svitavy District

Martinů composed his final works at his final residence, the Paul Sacher Estate in Switzerland. Paul Sacher, the conductor and pharmaceutical tycoon, had been one of Martinů’s most important supporters, having commissioned and or premiered several important works by the composer. When Martinů was hospitalized in Liestal in the summer of 1959, he wanted his marriage to Charlotte to be additionally blessed by the Church. Charlotte remembers that “We celebrated the wedding in his hospital room in the simplest, most human, most friendly manner.” After the ceremony, Maja Sacher took out a small case from her bag and gave Charlotte Martinů a diamond ring as a wedding present. Then she opened the bag, took out a few glasses and a bottle of champagne, and said something like this, “We must toast the marriage.” Martinů died of gastric cancer in Liestal on 28 August 1959, and he was laid to rest on the grounds of the Sacher Estate. A requiem mass was celebrated at the Roman Catholic Church in Pratteln on 1 September, and the composer laid to rest at the edge of the forest of the estate. In 1979, his remains were transferred with “great ceremony from the Sacher Estate to Czechoslovakia for reburial in his hometown of Polička.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Bohuslav Martinů: Nonet No. 2