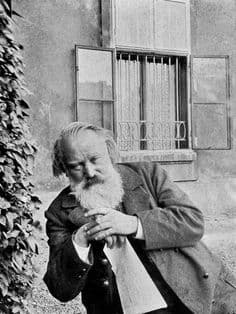

Brahms 1896

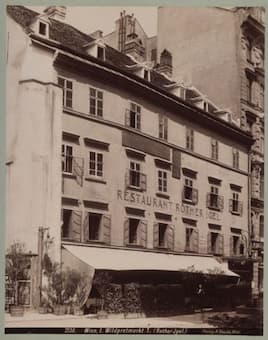

Johannes Brahms was certainly open to life’s pleasures, and he would never decline a good meal. He once told a friend, “I live in Vienna as if I were in the country,” and he ate his lunch at the same restaurant every day. The “Rother Igel” (The Red Hedgehog) was a famous tavern close to St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna that hosting musical performances and swarmed with celebrated musicians and countless music critics.

The “Rother Igel” (The Red Hedgehog)

Brahms, always eating in the company of friends, was very fond of beef goulash, and he had a special weakness for beef pilaf. He loved a jug or two of beer, and for special occasions, the restaurant kept a small barrel of the finest Hungarian Tokay for his private consumption. He also loved herring salad, and there was a rumor that “when opening a can of sardines, Brahms would drink the oil directly out of the can.” After lunch, Brahms “would stop at the Casino in the Stadtpark for relaxation… seated at a little marble table on the high terrace, sipping his coffee seasoned with a glass of cognac and eagerly reading the daily papers.” The good life in the Imperial City eventually took its toll, and Brahms was significantly overweight but basically healthy.

Johannes Brahms: Four Serious Songs, Op. 121 (Hotter/Moore)

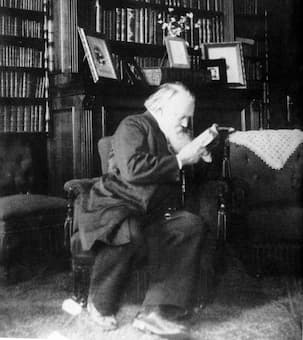

Residence and place of death of Brahms

in Vienna, Karlsgasse 4

The composer started to feel fatigued and ill at the end of May in 1896. Inexplicably, he started to lose weight and developed jaundice just a couple of months later. The whites of his eyes and the mucous membranes had started to turn yellow, and Brahms had access, and consulted the best doctors of his time. Leopold von Schrötter was an Austrian internist who became director of the world’s first laryngological clinic at the Vienna General Hospital, and by 1890 was named professor and director of the third medical clinic in Vienna. In addition to his expertise in the field of laryngology, Schrötter was involved in cutting-edge research on heart and lungs diseases, and with British surgeon James Paget, the eponymous Paget-Schrötter disease is named. The German-born specialist of internal medicine Hermann Nothnagel also briefly saw Brahms as a patient. He had been appointed full professor at the medical clinic in Jena in 1874, and was appointed professor at the university clinic in Vienna. A famed physician and researcher, the “Nothnagel syndrome,” a condition describing the irregular pulse associated with atrial fibrillation is named after him. In Vienna, Nothnagel’s department also housed the practice of Sigmund Freud. In addition, Brahms maintained a close personal friendship with the famed surgeon Theodore Billroth.

Johannes Brahms: 4 Piano Pieces, Op. 119 (Paul Lewis, piano)

Brahms at home on Karlsgasse 4

Doctors continued to observe Brahms for several months as his condition worsened with interchanging episodes of ravenous appetite and nausea, “generalized itching, growing immobility and episodes of bleeding.” On 1 February, Brahms consulted Josef Breuer, the family doctor of his close friend Ignaz Brüll. “Breuer at once recognized the hopelessness of Brahms’s condition, which he attributed to an advanced cancer of the liver, and he accordingly devoted his efforts to alleviating his patient’s physical suffering and provided moral support.” Breuer attempted to hide the grave nature of the illness from Brahms, even telling him that “he would be experiencing a great weakness before long as a necessary stage in the transition to his ultimate recovery.” Brahms described Breuer as an “excellent doctor,” and seemingly remained optimistic about his changes of recuperation. After Brahms’ death, however, Breuer expressed the opinion that Brahms “could hardly have been unaware of the gravity of his illness.” Brahms certainly knew that his cancer had reached terminal stage, as he told a friend a couple of weeks before his death, “I will soon make a long, long journey of which you will hear.”

Johannes Brahms: Organ Chorale, “O World, I have to leave you,” Op. 122, No. 11

Brahms on his Deathbed

Brahms was last publically seen at a performance of his 4th Symphony on 7 March 1897, and shortly thereafter he quietly attended the premier of the Strauss operetta “The Goddess of Reason.” On 25 March Brahms suffered a severe intestinal bleeding, and his condition reached a critical stage on 2 April 1897. Dr. Josef Breuer’s son Robert was in attendance during the last night of Brahms’s life. Brahms complained of some pain around midnight, and Breuer administered a morphine injection. At about 4 in the morning he gave Brahms a glass of Rhine wine for his thirst, and Brahms drank the wine slowly and with pleasure. Evidently he said afterwards, “Ah, that tastes good.”

Grave of Brahms

Such were the last words that Breuer heard Brahms speak. Breuer left shortly after 7am in order to return to his clinic, and he was therefore not present when Brahms died around 8:30am on 3 April 1897. Eugen von Miller took a photograph, Ludwig Michalek drew a pencil sketch, and Karl Kundmann molded the death mask. It was decided to not perform an autopsy, and liver carcinoma is often mentioned as the cause of his death. More recently, however, it has been suggested that the cause of death was neuroendocrine pancreatic cancer with liver metastasis and eventual liver failure. Brahms was sealed into his casket on 4 April and buried at Vienna’s Central Cemetery on 6 April 1897.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 4 in E minor, Op. 98