Benjamin Britten was admitted to the National Heart Hospital on 2 May 1973. Under the care of the cardiologist Graham Hayward, Britten’s medical history noted a heart murmur in infancy and an episode of pneumonia. Aortic regurgitation was detected in 1960, and his condition was complicated by endocarditis in 1968. A physical examination found “typical features of a severe aortic valve leak. The aorta was dilated but not aneurysmal, and the left ventricle was dilated.”

Benjamin Britten

In the medical opinion of the days, “the longstanding aortic valve leak and dilated left ventricle meant that Britten’s heart was not going to recover fully and that his life expectancy was limited, even with successful surgery.” Donald Ross performed the operation on 7 May 1973, describing the external appearance “of the heart as having an enlarged, bulky and flabby myocardium with a distended pulmonary artery root and poorly contracting left ventricle.” While the operation note did not consider the procedure to have been particularly challenging, a more recent account states, “The surgery and mop-up took six hours and was hugely problematic from the outset. There was a delay in Britten’s return to the ward due to the anticipated difficulty in coming off bypass, then ventricular ectopic and the growing awareness that he had suffered a stroke.”

Benjamin Britten: Death in Venice (excerpt)

Britten had indeed suffered a stroke, which affected his speech and his right side. And while his condition improved over time, “his right hand was permanently affected.” Not unexpectedly, according to his doctor, “Britten developed congestive heart failure, and over the next two years, he enjoyed a reasonable quality of life but his fatigue and malaise persisted; primarily due to his damaged left ventricle and also due to a progressive valve leak.”

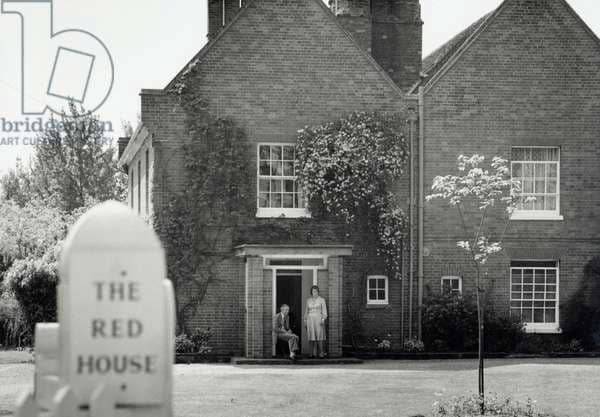

Britten and Rita Thomson, 1975

While Britten was in the hospital he became friends with the senior nurse Rita Thomson. They quickly developed a bond, and in 1974 she moved to The Red House in Aldeburgh to look after him full-time. After Britten’s death, she continued to take care of Peter Pears, and she remained in Aldeburgh for the rest of her life. In November 1976, Rita Thomson organized a champagne party for Britten’s 63rd birthday, and she invited his friends and his sisters Barbara and Beth. Britten died on 4 December 1976 of congestive heart failure, and his funeral service was held at Aldeburgh Parish Church three days later.

Benjamin Britten: String Quartet No. 3, Op. 94

In 2013, the conductor and music historian Paul Kildea incited a veritable shitstorm by suggesting that Britten died without knowing that he had tertiary syphilis, which led to the heart failure that eventually killed him. Kildea believes that Britten was infected by his partner of many years, the tenor Peter Pears. Pears, as it was argued, “was a carrier without symptoms of syphilis.” Britten apparently died without knowing why he failed to recover from surgery for aortic incompetence.

Britten and Pears

Kildea writes, “It was a series of tragedies, really. Syphilis did not kill him, but it meant that his heart was not in the condition required to recover completely from the procedure he underwent and from which his consultant, though not his cardiologist, expected him to make a full recovery.” Colin Matthews, a former assistant to the composer and board member of the Britten Pears Foundation wrote, “it’s beyond proof one way or the other since almost all those involved are either beyond speech or unwilling to speak, but for what it’s worth I think it is probably true. No one would have thought to call for a postmortem when he died. His heart was known to be failing and he died of heart failure, so that was that.”

Benjamin Britten: Phaedra (excerpt)

Kildea’s claim was quickly described as “complete rubbish,” and Britten’s consultant cardiologist explained, “that like all the hospital’s similar cases, Britten was routinely screened for syphilis before the operation, with negative results. Britten’s heart problem was degenerative, not syphilitic.” For some commentators, Kildea’s claim “leaves a slightly bitter aftertaste as it puts in doubt the image of Pears, and throws a shadow over one of the great partnerships in European arts.” For others, “the seven pages of speculation have marred what is otherwise a rather good book.”

Grave memorial of Britten

Of course, Britten’s stature as a musician is unaffected by the allegation, but the very public and outspoken denials, by people who could not possibly know one way or the other, clearly bares ideologically drawn fault lines. Speculations based on the medical conditions of Schubert or Schumann, for example, have not tarnished their reputation, why should Britten be the exception? Syphilis did carry a real stigma in Britten’s day, but as Colin Matthews summarizes, “Among most people I have spoken to in the last few days the reaction has been, so what?”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Benjamin Britten: “A Time there was…”