John Hoppner: Franz Joseph Haydn in London

Although Joseph Haydn had a wicked sense of humour, he musically never left anything to chance. When he accepted commissions away from his working place at Eszterháza, he conducted extensive research about the performers, the concert hall, and related matters so that he could adapt the music to the particular circumstances of the performance. In 1790 Haydn was invited by the impresario Johann Peter Salomon to compose and conduct first six, and later six more symphonies for the cosmopolitan audiences in London. Haydn was duly intrigued, and since the British hailed him as “the greatest composer in the world,” he was determined to live up to his stellar reputation. And in fact, the “London” symphonies are indeed his crowing achievements. A scholar writes, “Everything Haydn learned in forty years of experience went into these symphonies. While he did not depart radically from his previous work, he brought all the elements together on a grander scale, with more brilliant orchestration, more daring harmonic conceptions, more intense rhythmic drive, and especially, more memorable thematic inventions.”

Joseph Haydn: Symphony in D major, Hob. 104, I “Adagio-Allegro”

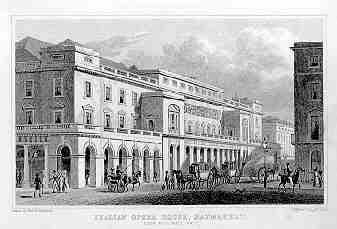

The Opera House, Haymarket, this building was destroyed by fire in 1867

Haydn carefully analyzed the tastes of his London audiences, but the process of composing brand new works in a very short period of time was made even more difficult by the arrival and hire of his student Ignaz Pleyel by a rival organization. Haydn writes to his friend Marianne von Genzinger in Vienna on 2 March 1792, “There isn’t a day, not a single day, in which I am free from work, and I shall thank the dear Lord when I can leave London—the sooner the better. My labours have been augmented by the arrival of my pupil Pleyel, whom the Professional Concert have brought here. He arrived here with a lot of new compositions, but they had been composed long ago; he therefore promised to present a new work every evening. As soon as I saw this, I realized at once that a lot of people were dead set against me, and so I announced publically that I would likewise produce 12 different new pieces. In order to keep my word, and to support poor Salomon, I must be the victim and work the whole time.”

Joseph Haydn: Symphony in D major, Hob. 104, II “Andante”

Italian Opera House, Haymarket

Haydn began to suffer from poor eyesight and he had many sleepless nights, but in the end, the competition with Pleyel spurred him to supreme efforts. In terms of orchestration, Haydn includes trumpets and timpani as well as clarinets. In several symphonies he features solo strings against the full orchestra, and he treated the woodwinds even more independently. “The whole sound of the orchestra achieves a new spaciousness and brilliance.” Haydn’s harmonic imagination comes to the fore in the slow introductions, which deliver a gripping dramatic suspense. Haydn was well aware that Pleyel was capable of writing beautiful melodies, and thus he turned to Slovenian, Croatian and other peasant tunes he remembered from his youth. A substantial number of movements sound characteristic folklike melodies and effects, including the imitation of bagpipes and allusions to “Turkish” band effects in passages featuring triangle, cymbals and bass drum. What made the “London” symphonies special was the fact that “Haydn always aimed to please both the casual music lover and the expert, and it is a measure of his greatness that he succeeded.”

Joseph Haydn: Symphony in D major, Hob. 104, III “Menuet-Allegro”

London Kings Theatre Haymarket

The Symphony No. 104 in D major is Haydn’s final symphony. It is the last of the twelve symphonies composed in London in 1795. The work premiered at the King’s Theatre on 4 May 1795 in a concert featuring exclusively Haydn’s own compositions conducted by the composer. Haydn probably did not intend the work as his symphonic testament, but it “mingled grandeur and earthy vigour, argumentative power and visionary poetry and concluded in a glorious final summation.” The nickname “London” apparently does not emerge from the fact that the work was composed and premiered in that city, but that the main theme of the “Finale” reminded listeners of a London street-cry to the words “Live cod!” or possible “Hot Cross Buns.” Today we know that it actually comes from the Croatian ballad “Oj Jelena,” which Haydn heard sung in Eisenstadt. The premiere was a resounding success. As a Haydn biographer wrote, “the big event of the season was Haydn’s benefit concert on 4 May, perhaps the greatest concert of Haydn’s life.” Charles Burney considered the new symphony “such as was never heard before of any mortal’s production,” and the Morning Chronicle reported “Haydn rewarded the good intentions of his friends by writing a new symphony, which for fullness, richness, and majesty, in all its parts, is thought by some of the best judges to surpass all his other compositions.” Papa Haydn was pleased as well as he wrote in his diary, “The whole company was thoroughly pleased and so was I. I made 4,000 gulden on this evening: such a thing is possible only in England.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Joseph Haydn: Symphony in D major, Hob. 104, IV “Finale”