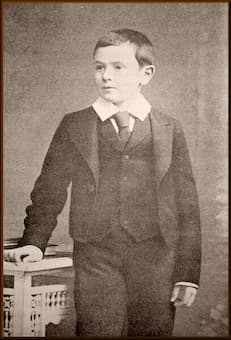

The young Antonín Dvořák

Since all of Antonín Dvořák’s predecessors were butchers or innkeepers, it was automatically assumed that he would inherit the business. However, in addition to the butcher’s trade the Dvořák family also cultivated another talent, namely, a flair for music. However, music making was regarded as a simple means to brighten up the daily routine and as a way to earn a little spare cash. “But it wasn’t long before everyone realized things would be somewhat different in Antonín’s case.” But let’s start in the beginning. Antonín Dvořák was born on 8 September 1841 in Nelahozeves, near Kralupy, as the first of 14 children, eight of whom survived infancy. His father František Dvořák worked as an innkeeper, a professional zither player, and a butcher. His mother Anna, née Zdeňková, came from a family of estate stewards in Uhy, and her father was the bailiff of the Prince of Lobkowicz. The Dvořák family operated a business in a cottage that had an inn on the ground floor. A fire broke out at that location in the summer of 1842, “and the future composer was rescued by his father who carried him to safety.”

Antonín Dvořák: “Forget-me-not Polka” (Ivo Kahánek, piano)

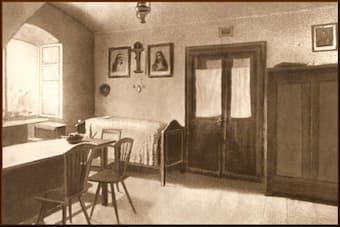

Dvořák’s birth room

Antonín’s musical talents were immediately apparent, and he received his first musical education in 1847 on entering the village school. His teacher, the Kantor Joseph Spitz taught him singing and gave him violin lessons. The boy soon participated in the musical life of the countryside, entertaining guests at village dances. He made his first solo appearance as a violinist in the local church in the nearby village of Veprek, but he was still expected to help his father with the family business. A charming anecdote tells that young Antonín visited the local livestock markets with his father. One day, he was tasked with walking home temperamental cattle from a village fair on a rope. Something apparently spooked the animal, and the boy was dragged into a lake. It was then and there that “he vowed in a flood of tears that he was never going to be a butcher.” At around that time, his father’s business was on the verge of going bankrupt, and he decided to move the entire family to the nearby town of Zlonice in 1853.

Antonín Dvořák: “Pauperia-Mazur” (Tomáš Víšek, piano)

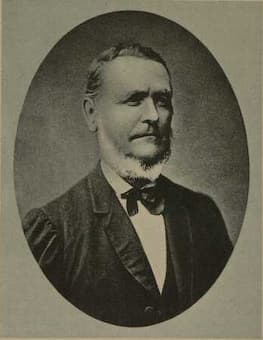

Antonín Liehmann

Antonín was sent ahead, primarily to learn the German language, and he lodged with his uncle Antonín Zdenĕk. In addition, he continued his musical education with the church choirmaster Joseph Toman and with the Kantor Antonín Liehmann. Liehmann taught the young boy music theory, and also instructed him on the violin, piano, organ, and in continuo playing. Liehmann was said to have had a violent temper, but Dvořák held him in the highest regard. “When I first went to Liehmann,” Dvořák later wrote, “he was teaching a boy how to play the piano. The boy might have been eight or nine years of age. I shall never forget how I felt when I heard that boy play. He played a polka and never made one mistake.” Dvořák continues, “Liehmann was a good musician, but choleric and old fashioned in his way of teaching. If the poor pupil could not play his piece well, he got as many blows as there were notes on the paper. In harmony he was well versed for his time. He had a good knowledge of counterpoint and read and worked out at the piano contrapuntal passages for his pupils. It often happened, however, that before we could decipher some of the thorough bass figures quickly enough to please him, blows would descend upon our blundering heads.”

Antonín Dvořák: “Prelude in D Major” (Hans-Ola Ericsson, organ)

Prague Organ School

Dvořák took additional organ and music theory lessons at Česká Kamenice with Franz Hanke, “who greatly encouraged his musical talents.” At the age of 16, through the urging of Liehmann and Zdenĕk, František finally allowed his son to become a musician, on the condition that the boy should work toward a career as an organist. As such, Dvořák was sent to the Prague Organ School, “which unlike the Conservatoire also provided tuition in composition.” Dvořák did not have very pleasant memories of his time at the organ school. In fact, whenever he mentioned the subject he spoke with a sense of bitterness. “At the school of organ,” he said, “everything smelt moldy, even the organ. Whoever wished to learn anything had to know the German language. Unless one had a grasp of the German language, one could not rise to the top in the school. I knew but little German, so whatever I did know I could not put into words. My fellow students used to look at me between their fingers and laugh at me behind my back. Their laughter did not cease, for even in later life they persisted in laughing at the audacity of my essaying composition. When they got to know that I composed, they would say among themselves: Look at that Dvorak! What do you think? He is dabbling in composition!” Dvořák graduated from the organ school in July 1859 with a public concert, at which he performed a Bach prelude and fugue and also two of his own works, the “Prelude in D major” and the “Fugue in G minor.”

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Antonín Dvořák: “Fugue in G minor”