On 9 May 1868, Anton Bruckner stepped onto the podium in the Austrian town of Linz. He stood in front of an orchestra consisting of members of the Linz theatre, regimental bands, and some local amateur musicians, and the premiere of his Symphony No. 1 in C minor was on the program. The orchestra was not really up to the technical demands of the work, but the critic Eduard Hanslick was in the audience and wrote a favorable review.

Anton Bruckner, 1889

“Bruckner was called back to the rostrum several times. When news of Bruckner’s forthcoming appointment at the Vienna Conservatory is confirmed, we can only congratulate this education establishment.” However, when dealing with the music of Anton Bruckner, nothing is really as straightforward as it appears to be. The composer had started work on this composition in January 1865. However, attempting to break away from the idea of an organically evolving symphonic process, he started with the “Finale.”

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 1 in C minor (1868 version, ed. T. Röder) “Finale” (Dresden Staatskapelle; Christian Thielemann, cond.)

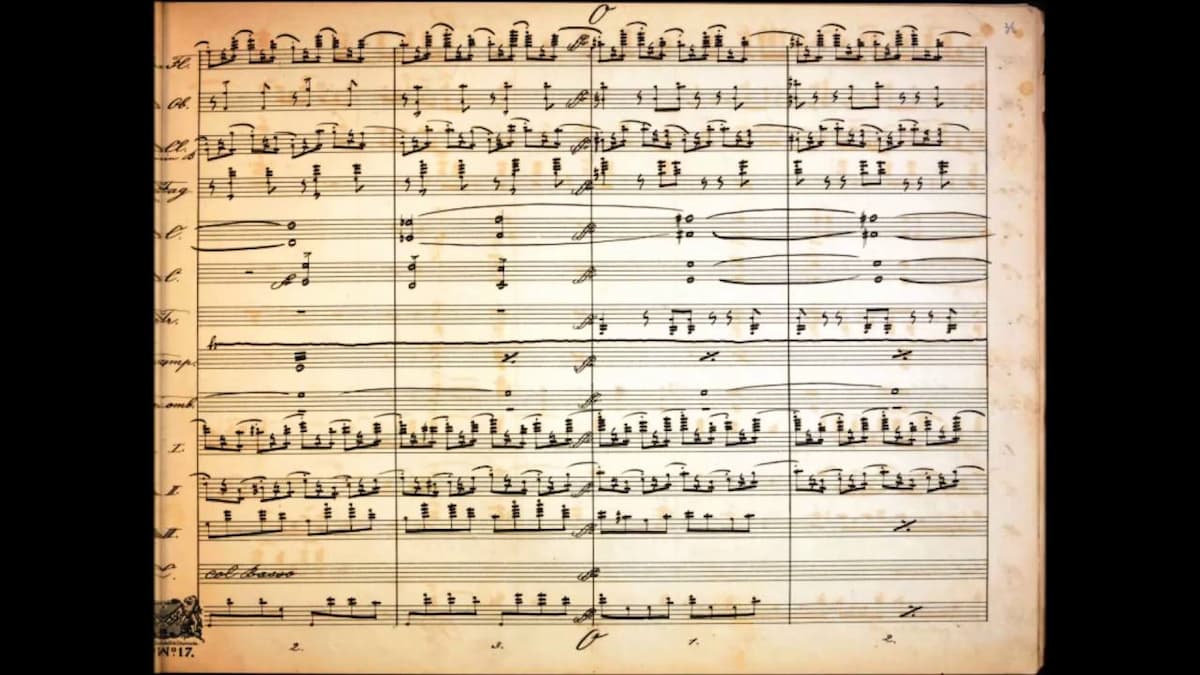

Bruckner’s Symphony No. 1

Bruckner later noted that in composing the “Finale,” he had “thrown caution to the winds and simply put his flashes of inspiration down in writing.” He even called this movement a “keckes Beserl” (cheeky lass), a Viennese slang expression for a high-spirited and sharp-tongues young woman. Bruckner would next turn his attention to the Scherzo and Trio movements, with his work completed by 25 May 1865. The opening movement was quickly added, and Bruckner traveled to Munich to attend a performance of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. However, the production had to be postponed because Mrs. Schnorr-Carolsfeld, singing the role of Isolde, was indisposed. Bruckner returned to Linz to conduct a choral festival, and subsequently traveled back to Munich to see the third performance of Tristan on 19 June. On that occasion, Bruckner was finally able to meet his idol in person, and Wagner gave him a signed photograph.

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 1 in C minor (1877 version, ed. L. Nowak) “Scherzo” (Dresden Staatskapelle; Eugen Jochum, cond.)

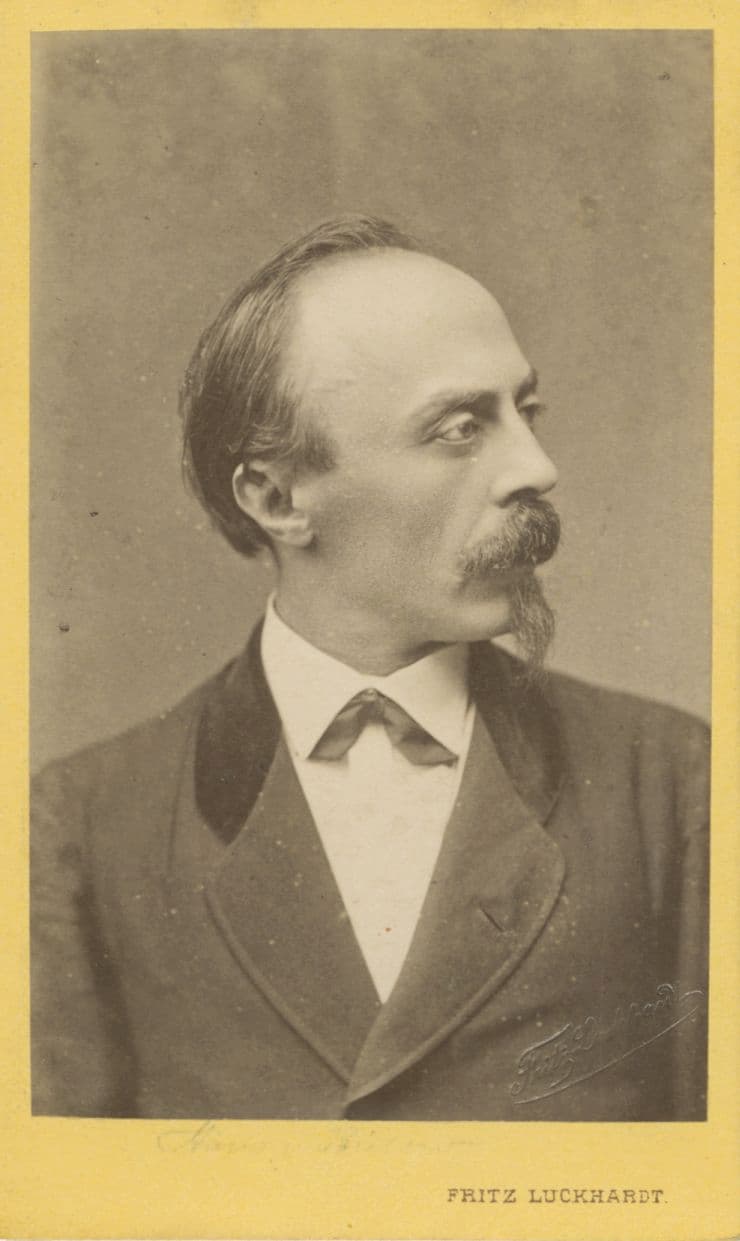

Hans von Bülow

During his Munich visit, Bruckner had the completed movements, the opening Allegro, the Scherzo, and the Finale in his back bag, but he was too shy to actually show them to Wagner. Instead, he showed his music to the conductor Hans von Bülow, who apparently commented on its “originality and boldness, on a number of fine ideas,” and “expressed his interest and surprise.” There can be no doubt that the experience of hearing Tristan had a tremendous impact on Bruckner. As a scholar writes, “It seems to have stimulated a great shift for Bruckner who was about to transform himself from a talented church musician to a major symphonic composer.” It also inspired him to continue work on his First Symphony. Bruckner composed a different Scherzo to replace the original movement but retained the original Trio section. He immediately continued with work on the “Adagio,” a movement completed on 14 April 1866.

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 1 in C minor (1866 version, ed. W. Carragan) “Adagio” (Royal Scottish National Orchestra; Georg Tintner, cond.)

Richard Wagner, 1871

Anton Bruckner was habitually plagued by debilitating periods of low self-esteem, making him a wide and easy target for music critics, journalists, and composers. One immediate result of this kind of bullying resulted in an obsession to endlessly revise and correct his compositions. You will already have noticed that my musical examples are all taken from different versions of the same work. However, the First Symphony is among Bruckner’s less complex cases, as the work exists in essentially two different versions. After completing the symphony in 1866, Bruckner revised it in 1890/91, resulting in the so-called “Vienna” version. Bruckner also made adjustments to the original “Linz” version in 1877. And we do know that Bruckner heard both the Linz and the Vienna versions performed in his lifetime. Most performances today feature the “Linz” version, and the “Vienna” version has “ basically vanished from concert halls and recording studios in spite of its authenticity.” Bruckner might well have considered the last Vienna versions as definitive, adding yet another twist to an already complicated story.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 1 in C minor (1891 version, ed. G. Brosche) “Allegro” (Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra; Günter Wand, cond.)

The new (Dec 2023) recordings of the Bruckner symphonies by Thielemann and the Vienna Philharmonic include the 1891 edition (the Vienna)with substantial revisions to that of the first version of 1866, the Linz, with small revisions published in 1877