Christoph Willibald Gluck

When Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787) set out to reform opera, he knowingly provided the spark for a full-out culture war. Gluck believed that the principal Italian operatic genres—opera buffa and opera seria—had become unnatural. Characters seemed nothing more than empty stereotypes, and the singing was devoted to superficial effects. That essentially meant ornamenting vocal line with such acrobatic flourishes that audiences could no longer recognize the original melody. Gluck wanted opera to return to its roots by focusing on human drama and passion and by giving equal importance to words and music.

Marie Antoinette

In 1770, Gluck signed a contract for six stage works with the management of the Paris Opéra. The driving force behind that contract was Marie Antoinette, who had become dauphine of France at the age of 14 in that very year. She was actually born an archduchess of Austria, and youngest daughter of Empress Maria Theresa and Emperor Francis I. Gluck immediately made his mark on the Parisian operatic scene, and a staging of Alceste made the composer a darling of the court and the public.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Alceste (Excerpt)

Jeanne Bécu Du Barry, 1781

However, Gluck’s operas on dark and dramatic Greek themes, a scarcity of incorporating ballets and a general lack of light melody did not sit well with aficionados of Italian opera. And Marie Antoinette’s growing influence at court did not sit well with Jeanne Bécu Du Barry (1743-1793). Madame du Barry, known as the last mistress of King Louis XV, was the illegitimate daughter of a seamstress and a monk, who initially became the mistress of Jean Baptiste du Barry, “a high-class pimp who owned a casino and prepared Jeanne for a career as a courtesan.”

Niccolò Piccinni

Jean Baptiste du Barry saw the huge potential of installing Jeanne as the chief mistress of the King of France. He faked her birth certificate, provided her with a noble lineage, and Madame du Barry was formally appointed chief mistress in 1769. Du Barry and Marie Antoinette had a famous falling out at their first face-to-face meeting, and the Italian du Barry had no love for Gluck’s music. She decided to set up a rival composer, and sent for Niccolò Piccinni (1728-1800) one of the most popular composers of Neapolitan opera buffa. But what is more, du Barry convinced the directors of the Paris Opera to engage Piccinni for writing an opera on a libretto that had already been contracted to Gluck.

Niccolò Piccinni: Roland (Luca Grassi, baritone; Alla Simoni, soprano; Stefania Donzelli, soprano; Sara Allegretta, soprano; Hyun-Dong Kim, tenor; Daniele Gaspari, tenor; Elena Lopez, soprano; Giacomo Rocchetti, baritone; Lei Ma, soprano; Bratislava Chamber Choir; Orchestra Internazionale d’Italia; David Golub, cond.)

Marriage of dauphine of France and Louis XVI, 1770

The libretto in question originated in one of Quinault’s tragedies “Roland,” and Piccinni had to compose music to words in a language unknown to him. His tutor writes, “line by line, word by word, I had everything to explain, and when he had laid hold of the meaning of a passage, I recited it to him, marking the accent, the prosody, and the cadence of the verses. He listened eagerly… and his delicate ear seized so readily the accent of the language and the measure of the poetry, that in his music he never mistook them.”

Marie Antoinette, 1778

Piccinni’s arrival in Paris had been kept a secret, but a close Gluck supporter had managed to ascertain the secret and informed the composer who was in Germany at that time. He also informed the press, and things started to get seriously out off hand. Supporters on both sides became militant, and the most popular question of the day “are you a Piccinnist or a Gluckist” secured or destroyed friendships, acquaintances and personal relationships. Gluck was accused of having fled to Germany because “he had no melody left in him,” and the Gluck supporter Abbé Arnaud asserted that “the chevalier is coming back with a “Roland” and an “Armida.” Gluck himself wrote a bitter and open public letter, and “epigrams and accusations flew back and forth like hailstones.”

Jeanne Bécu Du Barry, 1771

The public was caught up in a war of pamphlets, lampoons, and newspaper articles, and many of the greatest writers and thinkers of the time fought on opposite sides. Piccinni’s “Roland” was a huge success in Paris, with Gluck supporters sneering “at it as pretty concert music.” Nevertheless, Gluck apparently burned his score of “Orlando,” and finished his “Armida” instead. The opera was produced with success, but it could not eclipse Piccinni’s “Roland.” To be fair, the composers themselves took no part in the polemics, but the environment was decidedly poisonous.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Armide (Excerpt)

Marie Antoinette, 1775

Decidedly unhappy, Marie Antoinette made the next move in this fierce opera battle. She appointed Piccinni as her private singing teacher. The appointment was honorary and the composer received no pay. In addition, he was obliged to provide expensive copies of his printed compositions to the royal family. When the management of the Opera House had undergone some changes, the new director wanted to smooth things over and gave a lavish banquet. Both Gluck and Piccinni attended, and after plenty of champagne Gluck supposedly commented, “These French are good enough people, but they make me laugh. They want us to write songs for them, and they can’t sing.”

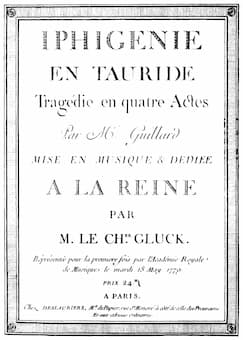

Iphigenia in Tauris by Gluck

This comment was seemingly made in response to the director’s suggestion that “both composers should write operas on the same subject, Iphigenia in Tauris. The French public would have for the first time the pleasure of hearing two operas on the same theme, with the same incidents, the same characters, but composed by two great masters of totally different schools.” Piccinni supporters demanded that his opera should be rehearsed and produced first, and the director agreed. Gluck supporters objected, but the director asserted, “I give you my word of honour that your opera (Piccinni) shall be put in rehearsal and brought out as soon as it is finished.” Both composers went to work, however, there is an additional twist to the story. Before Piccinni was able to finish his Iphigénie, he found out that Gluck had completed his opera and that it was already in rehearsal. Piccinni strongly protested, but the director excused himself by claiming that it had been a royal command. Clearly, Marie Antoinette had interfered again.

Christoph Willibald Gluck: Iphigénie en Tauride (Excerpt)

Jeanne Bécu Du Barry

Gluck’s masterpiece produced an unparalleled sensation in Paris, and for a while even his enemies fell silent. Piccinni himself is said to have been in awe at the “profound, serious, and wonderfully dramatic composition of his rival.” In fact, Piccinni decided to completely withdraw his Iphigénie, but the director insisted that it should be performed. Piccinni was rightfully nervous, and he had engaged the famed Mile Laguerre to sing the title role at the first performance. I suppose Mile Laguerre was rather nervous as well as she hardily fortified her nerves with plenty of alcohol before the performance.

Piccinni Statue in his hometown Bari

“She came on stage, and could not stand straight from intoxication. She made faces at the musicians and at the men in the pit. She flopped about and reeled through her part until the climax was reached.” When a member of the audience cried out, “This is not Iphegenia in Tauris but Iphegenia in Champagne,” the entire house roared with laughter. Mademoiselle Laguerre was arrested and marched off to prison to sober up. She returned to the stage fully recovered two days later, and “sang divinely and with exquisite effect.” Laguerre became the champion of the Piccinni faction and Sophie Arnould was the principle exponent of Gluck’s heroines. “The rival factions made the names of these charming and capricious women their war-cries not less than those of the composers. The public bowed and cringed before these idols of the stage.” However, a good many music lovers started to get tired of the dispute, which was kept alive by the boulevard press as usual. A disgusted amateur poet wrote:

There is no art, no scientific boredom

Piccinni, Gluck, did not notice the tunes

Nature and birds alone dictate the music,

and Marmontel did not pay them.

The heated conflict was finally brought to an end by Gluck’s death. It was suggested that Sacchini would be set up in his place, but the new composer was very much a follower of Italian opera. In turn, the French revolution cut Piccinni’s career in Paris short and the composer returned to Naples. Marie Antoinette, as is well known, lost her head. Queen Caroline of Naples greatly disliked Piccinni on account of wounded vanity, and Piccinni was mobbed and his house burned. He was imprisoned for four years, and although Napoleon Bonaparte took a passing interest in his work, Piccinni died in poverty on 7 May 1800. Although he wrote 85 operas, his works are practically unknown today.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter

Niccolò Piccinni: Iphigénie en Tauride (Excerpt)