© Martha Asencio Rhine | Times

It may sound strange if I told you I get warned on a regular basis at work – but it might not be for the reasons you would think. I’m talking about the world of orchestral parts; often well-used, dog-eared pieces of manuscript decades of years old from which we make wonderful music. Over the years, these parts often accrue penciled markings from generations of previous players, leaving us with a treasure trove of helpful tips, warnings, jokes and, yes, phone numbers. I really did find someone’s phone number on the back of a symphony once. And no, I didn’t call it. Who do you think I am?

Firstly, why do we even write things in parts?

Well, the main answer is very simple. It’s why we write anything down: so we don’t forget it later. Things like dynamics or articulations sometimes get changed in rehearsals, especially when you’re playing in a different hall than usual and you have to adjust your levels in order to work in a certain space (although more on this later), and we sometimes mark big changes in our parts so we don’t forget in the concert and embarrass ourselves in front of audience and colleagues alike.

Perhaps the biggest mystery to an outsider would be: What exactly do we write in parts?

Even from a young age we are taught to write things in our parts that we forget – missed accidentals, dynamics we might ignore, and so on. As we grow and develop, these type of markings diminish, as with training we learn to read and perform every single thing that is on the music in front of us – one reason why professional orchestras can get to grips with a new piece so quickly.

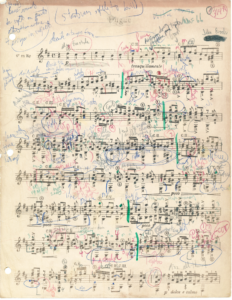

With that said, there are still things that potentially trip us up. In chromatic music at a fast speed, for example, we can only process so much, and so we can leave little hints and reminders to help us to get through without any slips. For example, on the music opposite, you can see the pattern is lots of ascending pairs of semitones, but then after the line break there is a continuous chromatic scale. A simple upwards arrow reminds me not to get into autopilot with the first pattern, and that there is change afoot!

In this second example, the music jumps around a lot, but after the line break, I start on the same note I just finished on (the C-natural). The horizontal line helps me to remember to keep my fingers in place ready for the next bar.

These are just a couple of things we might mark in our parts – other things include unexpected changes of time- or key signature, tempo changes, and perhaps most importantly, the caesura, or in other words, the silent pause which abruptly interrupts the music before restarting again. Do you want to be the only person in the orchestra who ignores the stop and charges loudly on, completely alone? No, I didn’t think so.

Apart from that, I try and write as little in my part as possible. I want to avoid over-marking my music and making the markings that are actually there useless!

Françaix: Divertissement for Oboe, Clarinet and Bassoon – II. Allegretto assai (Arlequin Trio)

© douglasniedt.com

So by this point, you may be asking: How much is too much? Often we find ourselves confronted with the problem of a challenging acoustic – a boomy cathedral, or a dry studio. Should we write every single adjustment to our dynamics in our parts? NO! Why? Because firstly, as soon as the concert in that venue is over, all those tiny finicky markings become obsolete, and then whichever poor soul ends up with the part after you is confronted with a baffling array of alternative dynamics or articulations that make no sense to them.

Our training as musicians enables us (hopefully) to adjust on the go, meaning that you don’t have to mark in every single change in dynamic – it’s more about responding to what you hear immediately around you rather than following instructions on a page. Plus that way, the markings you do actually see remain helpful and pertinent (like tricky accidentals or rogue time signature changes, as mentioned above). One useful pencil marking easily gets lost among the twenty other mediocre ones, rendering the good one practically invisible.

Of course, everyone has their personal preference with regard to how much to write in their parts, but if you ever find yourself wondering whether to mark something in or not, spare a thought for the unknown person who will end up with the music after you – will your successor thank you for giving them a trick to get through a difficult passage, or curse you under their breath for littering the part with tons of unnecessary annotations?

I like the idea of an accumulated bank of ideas and hints to navigate through thorny areas of our repertoire, while others want a totally blank canvas with no distractions whatsoever. Whatever your preference, I think we can agree on one thing: leave the phone numbers off. That’s just asking for trouble…