The powerful start to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony has meant various things over the centuries. During his time, according to his assistant, the music was taken to signal Fate knocking at the door. During the second world war, it was a signal of victory, despite being written by someone from the opposing side, because it was the same as the Morse code for the letter “V”. For most listeners, it’s the unforgettable start to a work that couldn’t be further from the classical designs of Haydn and Mozart.

V for Victory Pin

As we can see from his sketchbooks and initial drafts, Beethoven began writing the work in 1804. He was at work on other pieces at the same time, so progress on the symphony was constantly interrupted. Between 1804 and the work’s completion in 1807, he also composed the opera Leonora (which would later become the opera Fidelio), Piano Sonata Nos. 22 and 23 (Appassionata), Symphony No. 4, and Piano Concerto No. 4, as well as the three Op. 59 string quartets (Razumovsky) and a violin concerto.

Finally, on 22 December 1808, the work received its premiere. The 22 December concert became infamous for its length: the programme included Symphonies Nos. 5 and 6, Piano Concerto No. 4, the Choral Fantasy, extracts from the Mass in C, a solo piano improvisation by Beethoven, and the scena and aria Ah! Perfido. The concert was over 4 hours long, the hall was cold, the orchestra was under-rehearsed, and there were many stops and starts. The concert was intended to be a benefit concert for Beethoven, but the final amount of money taken was never revealed. However, one of his patrons gave him a present of 100 guldens in support after the concert.

Newspaper coverage of the concert found that given the amount of music performed, plus the fact that the music was all new, it was impossible to review. A composer who attended, Johann Friedrich Reichardt, dryly remarked: ‘… we sat, in the most bitter cold, from half past six until half past ten, and confirmed for ourselves the maxim that one may easily have too much of a good thing, still more of a powerful one’

Despite the unfortunate premiere of the work, it has become one of the standards of the orchestra repertoire. For many, it shows the new romantic era: not merely driven by beautiful melodies but equally driven by strong rhythmic forces. The ‘short-short-short-long’ of the opening sets the mode for the first movement. Every theme that follows derives from those four notes. Even in the usually strict first movement sonata form, Beethoven has his own innovations: the 4-note introduction, the lack of commitment to either C major or C minor, the development section that is introduced by the horns, the reduction of the 4-note motif down to a single note, and, then, in the recapitulation, the solo voice of the oboe sings out. The first movement closes firmly in the dark depths of C minor.

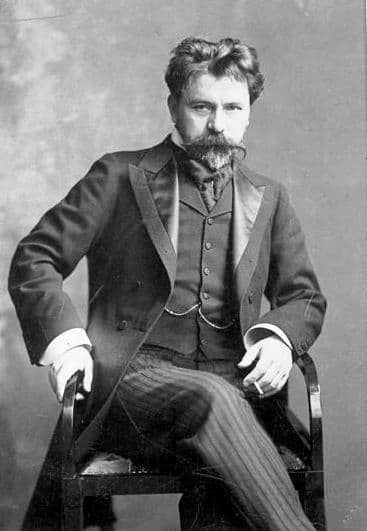

Nicola Perscheid: Arthur Nikisch, 1901

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 – I. Allegro con brio

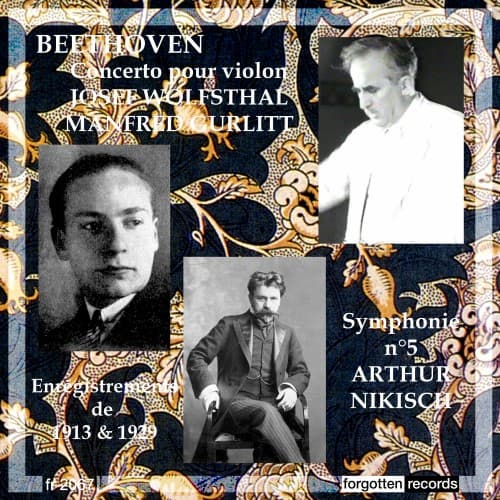

This very early recording dates from 1913 and was made by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Arthur Nikisch. Hungarian conductor Arthur Nikisch (1855-1922) started at the Vienna Conservatory at age 11 and won prizes for composition and violin. His first job was as a violinist in the Vienna Philharmonic in 1872, and by 1879 he was the first conductor for the Leipzig Opera; his second conductor was Gustav Mahler. His real fame, however, started in the US where he was a music director from 1889-1893. He then went to Budapest as director of the Royal Hungarian Opera in Budapest from 1893 to 1895. In 1895 he was appointed director of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra and principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, holding both positions until his death.

Elgar recording the symphony in 1914

This 1913 recording is said to be the first complete sound recording of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, but there was one made in 1910. This, more properly, would be the first recording by a well-known and famous symphony orchestra. The 1910 recording, on the Odeon label, is credited to Friedrich Kark and the otherwise unknown Odeon Symphony Orchestra. The recording would have been made using an acoustic horn, with the orchestra gathered around the recording device. Nikisch brought his firm grounding in Romantic music to this recording and it provides valuable insight into performance practice of the early 20th century. The repeats in the music are omitted because of the limited time on the recording medium.

Performed by

Arthur Nikisch

Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Recorded in 1913

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter