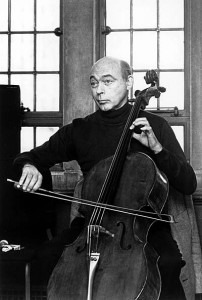

It was one thing to be accepted at age 22 to study with the great cellist and pedagogue Janos Starker at Indiana University. Adhering to his regimen of three lessons a week, each lesson on different repertory was another! Although I had heard stories about Starker’s intensely competitive class, I made up my mind. I was going to be the best Starker student who ever lived.

One of my favorite Starker stories concerns a talented young cellist who lacked the backbone necessary to lock himself in a practice room and make the stellar progress demanded of Starker students. One day in quiet frustration Starker said to him, “I wish I could chop off your hands and give them to someone more deserving!”

Indiana University School of Music is a competitive place, and we Starker students were really in the limelight. We were the envy of the whole school. On top of those pressures, I had been a very sheltered young lady, and this was my first time away from home. I was very lonely, so, I practiced. Every day I would plant myself in a tiny practice room and I wouldn’t get up for fear someone else might take my room. Three or four hours would pass. Eventually my left arm began to hurt.

I had embraced the prevailing mentality, that physical discomfort was an outcome of time well spent: “No pain, no gain.” I continued to play with a sore arm thinking that I could play through the pain and that it would just go away as I became a better cellist. But the pain got worse.

My first impulse was denial. I was wrong. Soon I got to the point when I could no longer ignore the pain and loss of function. It became so acute that I couldn’t use a knife and fork, or turn a doorknob, let alone play! I had let it go too long. I had developed a major case of what we now call overuse, or repetitive strain injury (RSI). At the time (1974) this came under the general heading of tendinitis or, as it was affectionately known at my school, “Bloomingtonitis.”

I went to several doctors and tearfully explained my problem. Their shrugging — unhelpful — responses ranged from disbelieving to insulting. Some asked, how can it hurt to play? It can’t possibly be as physically taxing as football playing or ditch digging. After all, music is so ethereal, and performing onstage is so glamorous.

“It’s all in your head” was another diagnosis. “You musicians are sensitive creatures perhaps you are being hysterical?” “You should consider changing your career,” said another doctor. What? Do something else? Inconceivable!

I went through a phase of utter desolation and panic. I would never play again. My life was essentially over, I thought. I certainly had no concept of how to face the challenge.

I was terrified to tell Starker. I had let him down! Immobilized by pain, fear and despair, wary of re-injury, I worked up the courage to tell him, and to his credit, he hid his horror quite well.

Starker is a master of ease and perfection. Together we set out to put my technique back together from scratch eliminating any tension, and focusing on ease of playing. I accepted my limitations (I am tiny at barely five feet tall) and I learned to recognize the danger signals. We took an analytical approach: Each motion was scrutinized from a whole-body use perspective. After a three-month rest period allowing my muscles to recover, it took six months to implement our strategy. After nine months I was cured and ready to become an advocate for injury prevention.

I do not fault those physicians so much now. I know that many musicians’ injuries affect soft tissue. They are harder to detect on standard medical tests. Consulting a physician experienced with repetitive strain injuries is essential for a proper diagnosis.

Since then, I have encountered countless musicians in various stages of denial or shame concerning their pain. Admitting to a problem ultimately means reckoning with it, making changes to playing technique or habits and oftentimes taking a hiatus from playing.

We’re all afraid of real or imagined stigmas associated with injury. Rationally or irrationally, we may wonder, does our pain signal that we have failed in some way? Will we be branded as bad musicians, flawed people?

Summer festivals and music camps can be particularly dangerous to your health. The inspiration of being amongst our peers and outstanding performers is offset by the frantic pace of performances and rehearsals and the pressures of new competition. When under these circumstances we also try to implement new techniques, we have a prescription for disaster. Prestigious schools and festivals frequently perpetuate a culture of overuse. These intensely pressured environments are virtual breeding grounds for injury.

Today, performing arts medicine is an established medical field. Clinics have sprung up all over the country. Music schools are advocating for injury prevention and there is awareness as never before. Fortunately, when we are armed with a little guidance regarding injury prevention it does not have to hurt to play.

“This is an excerpt from Playing (Less) Hurt by Janet Horvath, published by Hal Leonard Books”

A truly fascinating journey! Plus, very educational. Great article!