I was sixteen years old when I was first asked to turn pages. A fabulous young violinist was making his Toronto recital debut. I was thrilled to be allowed to purchase my first long gown for the occasion— it was lime green. I was an accomplished pianist. I could follow the music –no problem, I thought! The violinist turned out to be Pinchas Zuckerman and little did I know when I was recruited, that every time there was a red star in the piano music, I would have to gracefully and quietly get up from the piano to turn Zuckerman’s violin page and hurry back to the piano to (hopefully) find my place in the fast moving piano part. It didn’t help that I am quite petite. I donned the highest heeled shoes that I could find. Each turn, I nervously stretched across, teetering to the far right of the page, trying hard not to end up in the pianist’s lap.

I was sixteen years old when I was first asked to turn pages. A fabulous young violinist was making his Toronto recital debut. I was thrilled to be allowed to purchase my first long gown for the occasion— it was lime green. I was an accomplished pianist. I could follow the music –no problem, I thought! The violinist turned out to be Pinchas Zuckerman and little did I know when I was recruited, that every time there was a red star in the piano music, I would have to gracefully and quietly get up from the piano to turn Zuckerman’s violin page and hurry back to the piano to (hopefully) find my place in the fast moving piano part. It didn’t help that I am quite petite. I donned the highest heeled shoes that I could find. Each turn, I nervously stretched across, teetering to the far right of the page, trying hard not to end up in the pianist’s lap.

Christine Newland, a cellist friend of mine, has a similar story. Her first page- turning experience was for Daniel Barenboim at the request of his wife, the great cellist Jacqueline du Pré, for a recital. Christine was not confident that she could read the piano part well enough. She decided to follow the cello part, which is typically written above the piano score. Christine paid close attention to the instructions from Barenboim, to turn early, as most pianists read far ahead. Christine followed orders. Turn early…. As she flipped the first page, she was stunned when one of Barenboim’s hands flew forward. He noisily slapped the page back all the while playing multitudes of notes. After several more seconds Barenboim hastily turned the page himself. Much later Christine was told that Barenboim could be brutal with his page-turners.

Since then I have heard a multitude of page-turning horror stories. A colleague of mine decided to do her own turning for the difficult César Franck Sonata for Violin and Piano. She had had one too many bad page-turners in her career. At one point in the music, in her hurry to turn the page, she flipped several pages at once. Somehow she kept playing by ear and from memory. The pages seemed to be stuck together and the next thing she knew she had lobbed too many pages backward. The pages were pitched back and forth in a desperate dance until the pianist finally found her place in the music. By this time, profusely sweating, she had turned beet red and her heart raced. The audience thought that the pianist seemed so very inspired that evening.

Jewelry is an essential item for anyone who is onstage for the first time. A woman page-turner on one occasion had donned bangle bracelets on her right hand—the turning hand, for the concert. Prior to the recital the pianist had noticed the bracelets. Realizing that this could be a problem, the pianist suggested as kindly as possible, could she turn the pages with her left hand? The page-turner seemed to understand the reason for this instruction, or so the pianist thought. As they walked onto the stage the pianist noticed that the page-turner had moved her bangles onto her left wrist. The pianist was aghast. On the other hand (pun intended), the page-turner was delighted. Imagine how the bracelets might sparkle onstage— such a perfect match to the earrings of the pianist! Unexpected percussive effects ensued throughout the program.

Pages can be a challenge to turn during chamber music performances and orchestra concerts too. The cello side of the stage at Orchestra Hall in Minneapolis was breezy. Several years ago, the guest conductor for the week was Klaus Tennstedt a brilliant and demanding artist. We were performing Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Tennstedt was adamant that we play the beginning of the Ode To Joy almost inaudibly. The cellos introduce the melody first in the fourth movement. As we delicately put our bows to the string, afraid to move or breathe, our page fluttered. We watched with dismay as it slowly drifted, closing delicately two pages farther in the music. We dared not disturb the hushed mood. There was nothing to do but play the entire two pages from memory.

Page-turners who are utterly engrossed in the music can also be challenging to the performers. I remember a performance of the Chausson Concerto for Piano, Violin and String Quartet—a gorgeous work full of thrilling passagework for the pianist. He dazzled us with his beautiful playing. As the last line of the first page approached in the piano part, the page-turner made nary a move. He was so mesmerized by the music that he had closed his eyes to better lose himself in the music and he was actually humming along! The pianist hissed (quietly of course) “Psst! Hello? Turn the page and shush!” at which point the moon-struck page-turner leapt to his feet. This scenario continued throughout the piece until the page-turner finally succeeded turning one page on time despite his dream state. When the page-turner tried to sit back down he missed the chair entirely and fell flat on his behind.

Perhaps we musicians should consider placing an ad:

Experienced page-turner needed. No jewelry, no counting or singing along. Must be taller than five feet two.

Page turning mistake

More Behind the Scenes

-

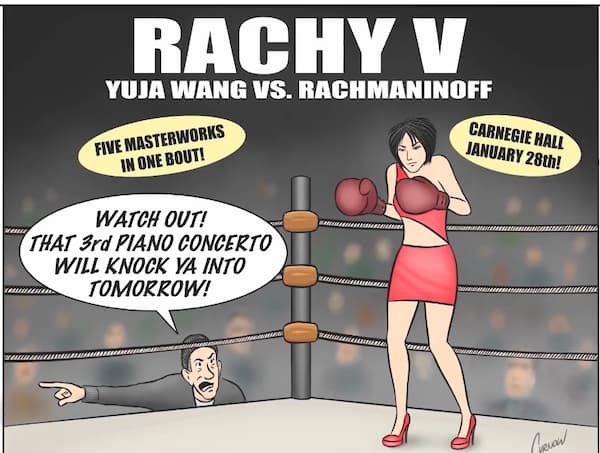

Musicians in Sync – What Yuja Wang’s Heartbeats Tell Us Discover how Yuja's heart raced through 97,076 notes in the Rachmaninoff marathon

Musicians in Sync – What Yuja Wang’s Heartbeats Tell Us Discover how Yuja's heart raced through 97,076 notes in the Rachmaninoff marathon -

The Goldilocks Principle in the Performance of Music “Allow everything to move that needs to move”

The Goldilocks Principle in the Performance of Music “Allow everything to move that needs to move” -

BodyMinded Thinking for the Fingers and Thumbs Learn about the ease of movement, control and power of your fingers

BodyMinded Thinking for the Fingers and Thumbs Learn about the ease of movement, control and power of your fingers -

BodyMinded Thinking for Dynamic Postural Support What should musicians be aware of as they are standing/sitting?

BodyMinded Thinking for Dynamic Postural Support What should musicians be aware of as they are standing/sitting?

Delightful article! People so rarely consider the stress of being a page-turner. I’ve done my fair share of turning pages for challenging performances. It’s one thing, being responsible for your own mistakes as a performer. It’s another, knowing that you can ruin another performer’s success!

Really enjoyed this! I once turned pages for violinist Lara St. John’s pianist for a recital. She was playing the Debussy Sonata. I got lost before a page turn because the pianist had drawn an alligator in his part… We both recovered. Incidentally, I always turn with my left hand, as in the photo and the video. Otherwise, I may accidentally hit the pianist in the head.

Oops — the photo shows left-handed turning, and the vid shows right-handed. hmmm… interesting. It was a pianist who told me to turn with the left hand.

A favorite “compliment” from audience members to page turners is, “You were so good, we didn’t even know you were there!” Also applies to collaborative pianists.