Paul Klee (1879-1940) in his Studio at the Bauhaus

“One day I must be able to improvise freely on the keyboard of colors: the row of watercolors in my paintbox”

Paul Klee (1879-1940), son of a German music teacher and a Swiss mother, started studying violin as a child, and as a young adult, played in the Berne municipal orchestra. Early on, he developed musical preferences for Johann Sebastian Bach and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and showed promise for a career in music. By 1898, however, he was studying art in Munich. During the early years of the 20th century, he traveled extensively in Italy and France. In Paris, he studied the works of Goya, Velazquez, Tintoretto, Watteau, Manet, Monet, Renoir and Cézanne.

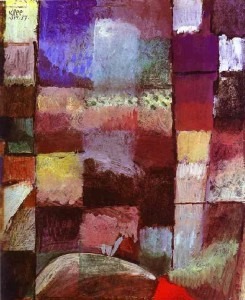

On a Motif from Hammamet

He finally settled back in Munich, joining exhibitions of Der Blaue Reiter Secessionist group which included artists such as Macke, Marc, Jawlensky, Münter, and Kandinsky. In 1914, Klee traveled to Tunisia, with visits to Hammamet and Kairouan – travels which changed his perception of color, leading him towards abstraction, and eliciting his statement “Color and I are one. I am a painter”.

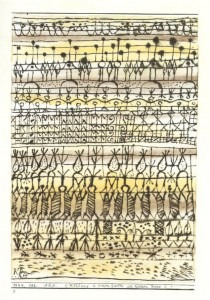

In the Style of Bach

In 1920, Klee was appointed to the Bauhaus faculty, and it was here, surrounded by the avant-garde in architecture, art, crafts and theatre, that his interest in and love of classical music and painting started to fuse. In his early paintings, he attempts to solve structural affinities between painting and music. The In the Style of Bach painting is conceived as a musical score with its implied linearity, and with plants, symbols and signs used as fermatas and musical pauses. The depicted visual rhythm becomes the percussive rhythm of a musical composition, similar to the polyphonic structures of the fugues of Johann Sebastian Bach — Bach, the master of counterpoint.

J.S. Bach: Prelude and Fughetta in E Minor, BWV 900 (Glenn Gould, piano)

Cooling in the Garden of the Torrid Zone

Many of Klee’s lecture notes to Bauhaus students contain musical notations and explanations of the mathematical treatment of musical patterns. His painting Cooling in the Garden of the Torrid Zone is the very example of a painting which shows the rhythmic, musical structure of elements divided by horizontal lines similar to staves in a musical score with signs and characters simulating the notes of a musical bar. Just as in the fugal structure in the E-minor Fugue by J.S. Bach (which Klee illustrated in his sketchbooks), there is a balance between regular elements and irregularities, creating tension and, in turn, repetitive structures perceived as rhythmic. Many of Klee’s titles for his paintings are funny and seemingly in the realm of fantasy — again linked to the concept of an open interpretation, as I have discussed previously in many of my articles on music and the arts.

Polyphony

Often, the titles of his paintings refer to music directly, such as Harmony in Blue-Orange, 1923; Rhythms of a Planting, 1925; Variations (Progressive Motif), 1927; New Harmony, 1934; The Entry for the French Horn, 1939, etc. In his painting Polyphony, 1932 Klee uses color to express his musical ideas. Background color blocks simulate the deep base chords of a musical composition, but then on the painting’s surface, Klee superimposes tiny dots in different colors in luminous fashion — acting here too like the counterpoint of Bach’s polyphonic musical structures.

Jacques Offenbach: Les contes d’Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann), Act IV: Belle nuit, o nuit d’amour … Amis, l’amour tendre et reveur! (Ann Murray, mezzo-soprano; Jessye Norman, soprano; Brussels National Opera Chorus; Brussels National Opera Symphony Orchestra; Sylvain Cambreling, cond.)

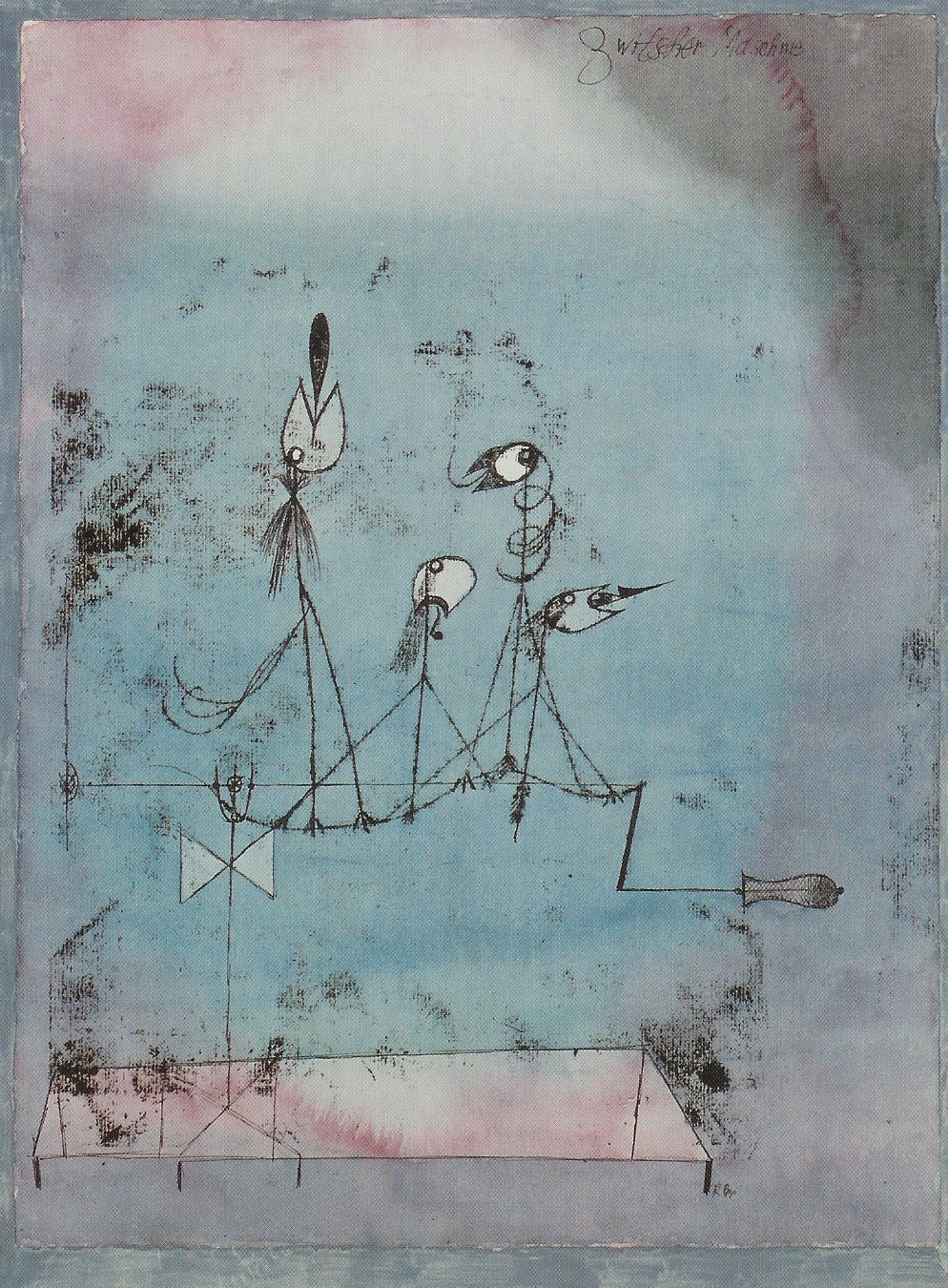

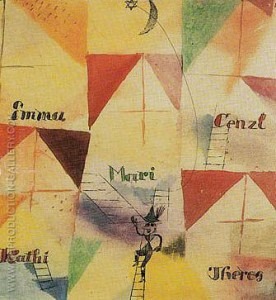

Hoffmannesque Fairy-tale Scene, 1921 5

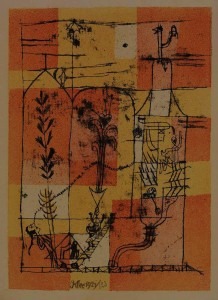

Many other Klee’s paintings are inspired by his love for certain operas. His print Hoffmanesque Fairy Tale Scene was inspired by Jacques Offenbach’s opera The Tales of Hoffmann, which Klee had attended on many occasions. This print appeared in Klee’s first portfolio of Bauhaus prints and shows an abstract depiction of the fairy tale characters, which are first drawn and then covered with an application of color — again referencing a polyphonic musical structure by combining the basic structure of underlying forms with creative, fantastic and imaginative components. Klee’s painting based on his favorite opera, Mozart’s Don Giovanni (watercolor and pen on paper) illustrates this as well — treated here ironically (the stick figure wearing a Bavarian hat), which according to him combines a dualism: “All that is devilish must be fused simultaneously with all that is celestial… Dualism should not be treated as such but rather as a complimentary whole… Truth requires the consideration of all elements, the work of art — a fusion of them all” (Klee’s Diaries, p. 380, letter of July 17, 1917 to his wife, Lily). Klee’s experiments with artistic techniques, the expressive power of color, the application of paint in unusual non-academic fashion – for example by in spraying and stamping on burlap, cardboard and muslin — also play into the interpretation of his work — again opening the possibilities of their multiple interpretation.

Don Giovanni – Là ci darem la mano

The Bavarian Don Giovanni

Finally, it is very interesting to note that even though Klee was a close friend of Kandinsky (himself a great friend of Arnold Schönberg), Klee was not interested in the theatrical productions and contemporary music at the Bauhaus — there is no reference to this anywhere in his diaries. Klee, like his friend Lyonel Feininger, also a classical musician and painter, appreciated foremost the composers of the Baroque and Classical periods, using and translating their polyphonic structures and their variations of themes as the basis for his luminescent, rhythmic and colorful works of art.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up to our E-Newsletter